The importance of imaging in the diagnosis of gastric diverticulum: a case report

Hadi Sasani1*, Nergis Ekmen2, Mehdi Sasani3

1Department of Radiology, Near East University Faculty of Medicine, Nicosia, TRNC.

2Istanbul Bilim University Faculty of Medicine, Florence Nightingale Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Istanbul, Turkey

3Trakya University, Medical Faculty, Department of Anatomy, Edirne, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hadi Sasani, MD

Specialist, Department of Radiology, NEU Faculty of Medicine, Near East Boulevard, 99138, Nicosia, TRNC.

Tel: +90(392) 675 10 00 /1132

E-mail: hadi.sasani@neu.edu.tr

Date of Received: November 30th, 2014

Date of Accepted: December 30th, 2016

Published Online: January 31st, 2017

© Int J Anat Var (IJAV). 2016; 9: 70–72.

[ft_below_content] =>Keywords

gastric diverticulum, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imagingy

Introduction

Gastric diverticulum (GD) is an uncommon condition seen and is outpouching of the gastric wall. It is being detected incidentally during routine diagnostic testing of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The prevalence of GD ranges from 0.04% in contrast study radiographs, 0.1-2.6% in autopsy series and 0.01%-0.11% at esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy [1-3].

GD may stimulate other pathologies. Imaging is crucial in detecting GD and also in differential diagnosis.

In this article, cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic findings of a patient with gastric diverticulum is presented.

Case Report

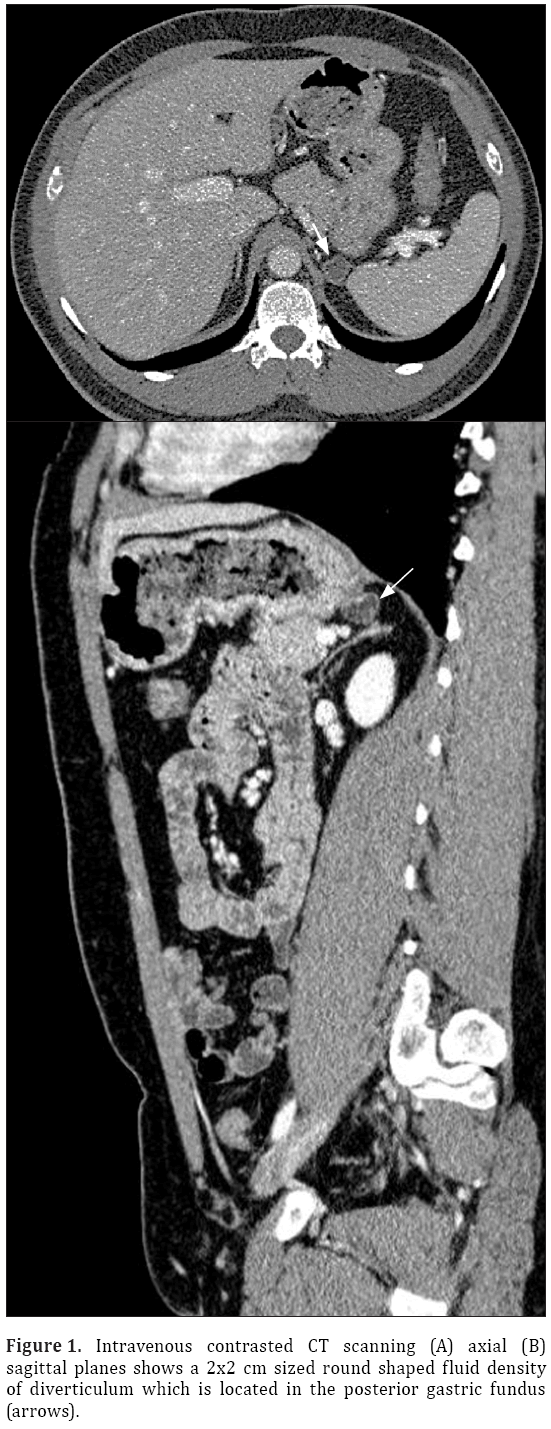

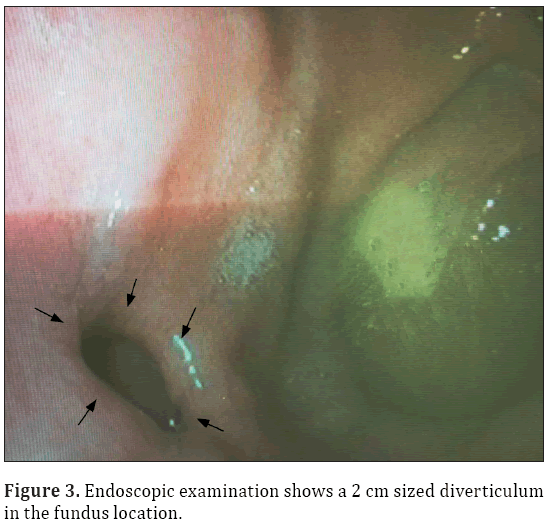

A 33-year-old male patient presented with complaint of abdominal pain. Physical examination and laboratory test were revealed normal (WBC: 5500 cells/μL, CRP:0.4 mg/L, ALT:20 U/L, AST:17 U/L). Intravenous contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2x2 cm sized nodular structure at the location posterior to gastric fundus and closed to the left adrenal gland ; the nodular structure was extending to the stomach (Figure 1). Because the examination was not an oral-contrast study, for differential diagnosis of other conditions (such as adrenal masses, cyctic-necrotic tumoral lesions, pancreatic pseudocyst, gastric wall duplication) abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was performed. In MRI, gastric diverticulum extending to the stomach was shown (Figure 2). The patient was underwent endoscopic examination, revealing a 2 cm diameter gastric diverticulum (Figure 3). There was no gastric content within the diverticulum. The patient was conservatively treated and followed.

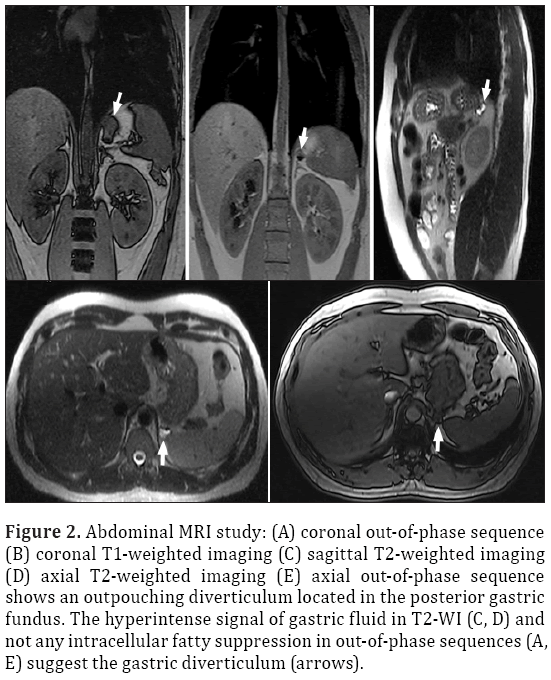

Figure 2: Abdominal MRI study: (A) coronal out-of-phase sequence (B) coronal T1-weighted imaging (C) sagittal T2-weighted imaging (D) axial T2-weighted imaging (E) axial out-of-phase sequence shows an outpouching diverticulum located in the posterior gastric fundus. The hyperintense signal of gastric fluid in T2-WI (C, D) and not any intracellular fatty suppression in out-of-phase sequences (A, E) suggest the gastric diverticulum (arrows).

Discussion

Gastric diverticulum usually occurs in middle-aged people (20-60 years of age), with its equal distribution in both sex [3]. They are often asymptomatic; however, they may be sometimes symptomatic presenting with dyspepsia, vomiting and abdominal pain. Complications such as ulceration, perforation, hemorrhage, torsion and malignancy are rare possibilities [4,5].

The etiology of GD may be acquired or congenital. Embryologically stomach is transformed from a fusiform swelling of the foregut into its adult form between the 20-50th days of gestation. Here, there is a 90-degree rotation of the stomach occurs. It carries the duodenal loop, the pancreas, and the dorsal mesentery. A diverticulum of the posterior gastric wall could herniate through an area of dorsal mesentery before its fusion with the left posterior body wall. At first, the diverticulum would lie superior to the pancreas. With further extension, the diverticulum could project posterior to the pancreas. The inferior aspect of the diverticulum would be adjacent to Gerota’s fascia and the left adrenal gland. If migration of the diverticulum occurs before renal ascent, the diverticulum would indent Gerota’s fascia and interdigitate between the left kidney and the left adrenal gland. However, after fusion of the dorsal mesentery it might lie within the lesser sac [3].

About 75% of GD are located in the posterior wall of the gastric fundus, 2 cm below the esophagogastric junction and 3 cm from the lesser curve. Diverticula are usually less than 4 cm in size (3-11 cm). False diverticula are either traction or pulsion and may be associated with inflammation or other diseases [6,7].

Radiologic studies (contrast radiographic study, CT, MRI) and endoscopic studies (esophagogastroduodenoscopy ) may be used to depict the gastric diverticulum. Upper gastrointestinal contrast radiographic study (UGI) or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) are the most reliable diagnostic tests, however, according to the literature the false negative results of these studies (particularly especially for a diverticulum with a narrow neck) have been reported [3,8]. Endoscopic evaluation is operator dependant. Therefore, to further clarify the pathology, cross sectional imaging modalities such as CT or MRI is needed.

CT scanning may be effective, however, the accuracy of CT because of the possible misdiagnosis is not widely accepted [3,9]. However, Schwart et al. Reported that diagnosis of a gastric diverticulum with a sectional imaging modality like CT is highly sensible [10].

CT may show an abnormally thin-walled rounded cystic mass with an air-fluid level in the region of the left adrenal and paravertebral region. Adrenal, pancreatic, and renal cysts, duplication cysts and diverticula of bowel are the conditions may be considered in differential diagnosis. Gas containing cystic masses may suggest infection, necrotic tumor, or a structure communicating with the gastrointestinal tract. Lesions such as abscess and necrotic neoplasm more commonly have a thick, shaggy wall [3].

Thanks to sequences (Fat-suppressed T2W short tau inversion recovery (STIR), half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE), T1 weighted spin echo (T1W SE), Out-of-Phase sequence images) using in MRI, they provide possibility to detect and differentiate structures and lesions from other underlying conditions. Thin walled cystic lesion with airfluid level and a connection to the gastrointestinal tract is the typical appearance of GD. However, as in our case, if there is no air containing diverticulum, it may be misinterpreted as a different structure. The visualization of its connection of the gastrointestinal tract in three-dimensional reconstruction imaging is crucial in differential diagnosis [11].

Conclusion

GD have variable symptoms and are often asymptomatic. Modalities such as CT and MRI may be useful in making differential diagnosis especially for the lesion in the left paravertebral region.

References

- Gockel I, Thomschke D, Lorenz D. Gastrointestinal: Gastric diverticula. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004; 19: 227–232.

- Donkervoort SC, Baak LC, Blaauwgeers JL, Gerhards MF. Laparoscopic resection of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum: a minimally invasive solution. JSLS 2006;10:525–527.

- Kodera R, Otsuka F, Inagaki K, Miyoshi T, Ogura T, Tanimoto Y, Sei T, Makino H. Gastric diverticulum simulating left adrenal incidentaloma in a hypertensive patient. Endocr J. 2007;54(6):969–974.

- Harford W, Jeyarajah R. Diverticula of the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. In: Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th Ed., Philadelphia (PA), Saunders. 2006; 465–477.

- Mohan P, Ananthavadivelu M, Venkataraman J. Gastric diverticulum. CMAJ 2010;182(5):E226.

- Rodeberg DA, Zaheer S, Moir CR, Ishitani MB. Gastric diverticulum: a series of four pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:564–567.

- Wolters VM, Nikkels PG, Van Der Zee DC, Kramer PP, De Schryver JE, Reijnen IG, Houwen RH. A gastric diverticulum containing pancreatic tissue and presenting as congenital double pylorus: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001; 33:89–91.

- Rashid F, Aber A, Iftikhar SY. A review on gastric diverticulum. World J Emerg Surg. 2012; 7:1.

- Araki A, Shinohara M, Yamakawa J, Tanaka M, Natsui S, Izumi Y. Gastric diverticulum preoperatively diagnosed as one of two left adrenal adenomas. Int J Urol. 2006; 13:64–66.

- Chasse E, Buggenhout A, Zalcman M, Jeanmart J, Gelin M, El Nakadi I. Gastric diverticulum simulating a left adrenal tumor. Surgery. 2003; 133:447–448.

- Schramm D, Bach AG, Zipprich A, Surov A. Imaging findings of gastric diverticula. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014; 2014:923098.

Hadi Sasani1*, Nergis Ekmen2, Mehdi Sasani3

1Department of Radiology, Near East University Faculty of Medicine, Nicosia, TRNC.

2Istanbul Bilim University Faculty of Medicine, Florence Nightingale Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Istanbul, Turkey

3Trakya University, Medical Faculty, Department of Anatomy, Edirne, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hadi Sasani, MD

Specialist, Department of Radiology, NEU Faculty of Medicine, Near East Boulevard, 99138, Nicosia, TRNC.

Tel: +90(392) 675 10 00 /1132

E-mail: hadi.sasani@neu.edu.tr

Date of Received: November 30th, 2014

Date of Accepted: December 30th, 2016

Published Online: January 31st, 2017

© Int J Anat Var (IJAV). 2016; 9: 70–72.

Abstract

Gastric diverticula (GD) are rare and are generally detected incidentally during routine diagnostic testing of the upper gastrointestinal tract. They can be congenital or acquired. GD may mimic other pathologies such as cyctic-necrotic tumoral masses. Multiplanar imaging plays an important role in detecting GD and differentiate them from other conditions.

In this article, we present imaging findings of a patient with gastric diverticulum.

-Keywords

gastric diverticulum, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imagingy

Introduction

Gastric diverticulum (GD) is an uncommon condition seen and is outpouching of the gastric wall. It is being detected incidentally during routine diagnostic testing of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The prevalence of GD ranges from 0.04% in contrast study radiographs, 0.1-2.6% in autopsy series and 0.01%-0.11% at esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy [1-3].

GD may stimulate other pathologies. Imaging is crucial in detecting GD and also in differential diagnosis.

In this article, cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic findings of a patient with gastric diverticulum is presented.

Case Report

A 33-year-old male patient presented with complaint of abdominal pain. Physical examination and laboratory test were revealed normal (WBC: 5500 cells/μL, CRP:0.4 mg/L, ALT:20 U/L, AST:17 U/L). Intravenous contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2x2 cm sized nodular structure at the location posterior to gastric fundus and closed to the left adrenal gland ; the nodular structure was extending to the stomach (Figure 1). Because the examination was not an oral-contrast study, for differential diagnosis of other conditions (such as adrenal masses, cyctic-necrotic tumoral lesions, pancreatic pseudocyst, gastric wall duplication) abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was performed. In MRI, gastric diverticulum extending to the stomach was shown (Figure 2). The patient was underwent endoscopic examination, revealing a 2 cm diameter gastric diverticulum (Figure 3). There was no gastric content within the diverticulum. The patient was conservatively treated and followed.

Figure 2: Abdominal MRI study: (A) coronal out-of-phase sequence (B) coronal T1-weighted imaging (C) sagittal T2-weighted imaging (D) axial T2-weighted imaging (E) axial out-of-phase sequence shows an outpouching diverticulum located in the posterior gastric fundus. The hyperintense signal of gastric fluid in T2-WI (C, D) and not any intracellular fatty suppression in out-of-phase sequences (A, E) suggest the gastric diverticulum (arrows).

Discussion

Gastric diverticulum usually occurs in middle-aged people (20-60 years of age), with its equal distribution in both sex [3]. They are often asymptomatic; however, they may be sometimes symptomatic presenting with dyspepsia, vomiting and abdominal pain. Complications such as ulceration, perforation, hemorrhage, torsion and malignancy are rare possibilities [4,5].

The etiology of GD may be acquired or congenital. Embryologically stomach is transformed from a fusiform swelling of the foregut into its adult form between the 20-50th days of gestation. Here, there is a 90-degree rotation of the stomach occurs. It carries the duodenal loop, the pancreas, and the dorsal mesentery. A diverticulum of the posterior gastric wall could herniate through an area of dorsal mesentery before its fusion with the left posterior body wall. At first, the diverticulum would lie superior to the pancreas. With further extension, the diverticulum could project posterior to the pancreas. The inferior aspect of the diverticulum would be adjacent to Gerota’s fascia and the left adrenal gland. If migration of the diverticulum occurs before renal ascent, the diverticulum would indent Gerota’s fascia and interdigitate between the left kidney and the left adrenal gland. However, after fusion of the dorsal mesentery it might lie within the lesser sac [3].

About 75% of GD are located in the posterior wall of the gastric fundus, 2 cm below the esophagogastric junction and 3 cm from the lesser curve. Diverticula are usually less than 4 cm in size (3-11 cm). False diverticula are either traction or pulsion and may be associated with inflammation or other diseases [6,7].

Radiologic studies (contrast radiographic study, CT, MRI) and endoscopic studies (esophagogastroduodenoscopy ) may be used to depict the gastric diverticulum. Upper gastrointestinal contrast radiographic study (UGI) or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) are the most reliable diagnostic tests, however, according to the literature the false negative results of these studies (particularly especially for a diverticulum with a narrow neck) have been reported [3,8]. Endoscopic evaluation is operator dependant. Therefore, to further clarify the pathology, cross sectional imaging modalities such as CT or MRI is needed.

CT scanning may be effective, however, the accuracy of CT because of the possible misdiagnosis is not widely accepted [3,9]. However, Schwart et al. Reported that diagnosis of a gastric diverticulum with a sectional imaging modality like CT is highly sensible [10].

CT may show an abnormally thin-walled rounded cystic mass with an air-fluid level in the region of the left adrenal and paravertebral region. Adrenal, pancreatic, and renal cysts, duplication cysts and diverticula of bowel are the conditions may be considered in differential diagnosis. Gas containing cystic masses may suggest infection, necrotic tumor, or a structure communicating with the gastrointestinal tract. Lesions such as abscess and necrotic neoplasm more commonly have a thick, shaggy wall [3].

Thanks to sequences (Fat-suppressed T2W short tau inversion recovery (STIR), half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE), T1 weighted spin echo (T1W SE), Out-of-Phase sequence images) using in MRI, they provide possibility to detect and differentiate structures and lesions from other underlying conditions. Thin walled cystic lesion with airfluid level and a connection to the gastrointestinal tract is the typical appearance of GD. However, as in our case, if there is no air containing diverticulum, it may be misinterpreted as a different structure. The visualization of its connection of the gastrointestinal tract in three-dimensional reconstruction imaging is crucial in differential diagnosis [11].

Conclusion

GD have variable symptoms and are often asymptomatic. Modalities such as CT and MRI may be useful in making differential diagnosis especially for the lesion in the left paravertebral region.

References

- Gockel I, Thomschke D, Lorenz D. Gastrointestinal: Gastric diverticula. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004; 19: 227–232.

- Donkervoort SC, Baak LC, Blaauwgeers JL, Gerhards MF. Laparoscopic resection of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum: a minimally invasive solution. JSLS 2006;10:525–527.

- Kodera R, Otsuka F, Inagaki K, Miyoshi T, Ogura T, Tanimoto Y, Sei T, Makino H. Gastric diverticulum simulating left adrenal incidentaloma in a hypertensive patient. Endocr J. 2007;54(6):969–974.

- Harford W, Jeyarajah R. Diverticula of the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. In: Feldman M, Friedman L, Brandt L, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th Ed., Philadelphia (PA), Saunders. 2006; 465–477.

- Mohan P, Ananthavadivelu M, Venkataraman J. Gastric diverticulum. CMAJ 2010;182(5):E226.

- Rodeberg DA, Zaheer S, Moir CR, Ishitani MB. Gastric diverticulum: a series of four pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:564–567.

- Wolters VM, Nikkels PG, Van Der Zee DC, Kramer PP, De Schryver JE, Reijnen IG, Houwen RH. A gastric diverticulum containing pancreatic tissue and presenting as congenital double pylorus: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001; 33:89–91.

- Rashid F, Aber A, Iftikhar SY. A review on gastric diverticulum. World J Emerg Surg. 2012; 7:1.

- Araki A, Shinohara M, Yamakawa J, Tanaka M, Natsui S, Izumi Y. Gastric diverticulum preoperatively diagnosed as one of two left adrenal adenomas. Int J Urol. 2006; 13:64–66.

- Chasse E, Buggenhout A, Zalcman M, Jeanmart J, Gelin M, El Nakadi I. Gastric diverticulum simulating a left adrenal tumor. Surgery. 2003; 133:447–448.

- Schramm D, Bach AG, Zipprich A, Surov A. Imaging findings of gastric diverticula. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014; 2014:923098.