Educating nurses how to critique research reports

Received: 08-May-2018 Accepted Date: May 25, 2018; Published: 04-Jun-2018

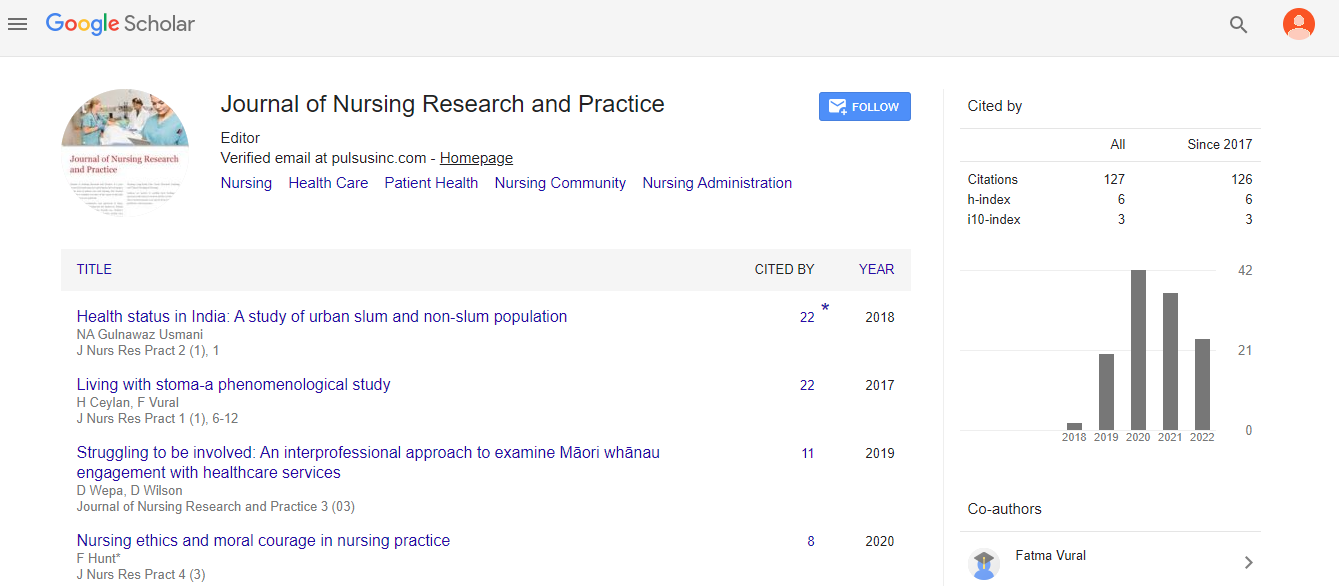

Citation: Pinkowski J. Educating nurses how to critique research reports. J Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2(2):32-34.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objectives: The primary objective of the study was to create an educational module informing bedside acute care nurses how to critique a research report, how to complete a literature review, and how to craft a table of evidence (TOE). The second objective was to ask five evidence-based practice (EBP) content experts to assess the educational module and provide feedback to ensure the content will assist nurses in learning how to read and understand research reports.

Methods: The consensus study included evaluations from five content experts who completed a scholarly evaluation of the EBP educational module. The study was granted permission and ethical clearance from Walden.

Results: Two common themes emerged from the experts’ review of the EBP teaching module. The first theme focused on expanding the module into a two-part series: Part 1: How to critique the article, and Part 2: How to organize and pool data. The second premise included adding an extra column at the end of the TOE with a grading scale to identify the strength of the research reports.

Conclusions: The module offers acute care nurses legitimate tools to use when assessing research reports to support their clinical practice with current best evidence. The content of the module introduces the hierarchy of evidence levels for nursing staff who lack knowledge and skills in reading and understanding research articles.

Keywords

Evidence-based practice origins; Evidence-based practice models; Evidence-based practice instruments; Barriers to implementation of evidence-based practice; Nursing beliefs and behavior related to evidence-based practice; Evidence-based health care; Research and nursing practice clinical practice

Introduction

Patient outcomes improve with the utilization of evidence-based practice (EBP) [1]. Most nurses agree EBP improves patient outcomes, increasing the safe and predictable care of patients [2]. However, nurses’ attitudes and beliefs related to using EBP in their personal practice are greater than their knowledge and skills related to implementing EBP [2]. Nurses need to be able to appraise research findings that support EBP to improve patient outcomes [3]. Investigative findings confirm that patient outcomes are at least 28% better when clinical care is based on rigorous studies [4].

Patient outcomes improve with the utilization of evidence-based practice (EBP) [1]. Most nurses agree EBP improves patient outcomes, increasing the safe and predictable care of patients [2]. However, nurses’ attitudes and beliefs related to using EBP in their personal practice are greater than their knowledge and skills related to implementing EBP [2]. Nurses need to be able to appraise research findings that support EBP to improve patient outcomes [3]. Investigative findings confirm that patient outcomes are at least 28% better when clinical care is based on rigorous studies [4].

Nurses working in acute care facilities have different levels of knowledge and skill related to EBP [2,5,6]. Nursing has been challenged by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to convert current research findings into evidence supporting clinical decision-making at the bedside. According to the IOM, patient care should be supported by current empirical evidence and should not vary from clinician to clinician or from place to place [7].

There are now specific criteria such as the Research Assessment Checklist (RAC) for appraising evidence and enabling the reader to evaluate weak or strong evidence findings [8]. The ability to assess evidence as valid or invalid enhances the process of integrating research into practice.

Principles based on EBP enable nurses to have the tools to improve clinical practice, resulting improved patient outcomes [2,9].

One of the ways health care organizations can integrate EBP to sustain patient care is through the education of bedside nursing staff regarding how to read scholarly literature [6]. The primary objective of this study was to create an educational module informing bedside acute care nurses how to critique a research report using the RAC, how to complete a literature review, and how to craft a table of evidence (TOE). The educational module is a power point presentation designed by the author and presented as an interactive learning activity. The second objective was to ask five EBP content experts to evaluate the educational module and provide feedback to ensure the content will assist bedside acute care nurses in learning how to read and understand research reports.

Research Design and Methods

Research design

A qualitative consensus design was used for this study.

Population and sampling

The participants identified for participation in this study were individual nurses with terminal degrees in their areas of expertise and at least 5 years of experience in a specific clinical practice area or academic setting.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality among content experts was maintained. Each expert interacted with the author of the study and not with other members of the panel. Confidentiality was maintained by not sharing the participants name with other individuals. The author was the only individual with knowledge related to the identity of the participants.

Data collection

Data collection took place using the following four-step procedure. The first step was to forward to the experts via e-mail an invitational recruitment letter explaining the purpose of the study and inviting them to participate in the review of the module. The invitational recruitment letter was used to confirm their qualifications as content experts. The second step was to forward a consent form via e-mail to each expert who indicated interest in participating in the review of the module. The third step was to forward the PowerPoint educational module to each expert, along with the modified SQUIRE 2.0 Checklist via e-mail [10]. Directions for use of the checklist as a guide for evaluating the module accompanied the checklist. The fourth step of the data collection process was to collect the completed SQUIRE 2.0 Checklists along with appraisal from the content experts.

Data analysis

The information provided from the experts’ answers and comments was assessed by the author of the study to identify similar themes. Data collected were used to determine whether the experts agreed with each of the methods used in the module and whether the methods were appropriate for bedside acute care nurses’ level of understanding. The evaluations from the content experts offered additional EBP information to enhance the methods utilized in the teaching module. Results of the experts’ reviews were presented in a narrative format.

Ethical considerations

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from Walden University prior to requesting the review of the educational module by the content experts. The content experts were informed regarding the purpose of the study. The experts were assured that all information provided by them would be kept confidential. Signed informed consent forms by the content experts indicated participation in the study was voluntary. The privacy of the participants was maintained by keeping the recruitment letters, signed consent forms and evaluations of the project by the experts in a locked safe with the combination known only to the author of the study.

Results

The review of the educational module by the content experts provided enhancement to the EBP content of the educational module. Two common themes emerged from the experts’ evaluation of the educational module. One theme was directly related to Statement 6 of the survey (Table 1), which states a “description of the methods used to inform bedside nurses how to read and understand research reports is presented in sufficient detail that others could reproduce it.” One expert suggested that more detail of the Research Assessment Checklist (RAC) would be helpful. Another expert suggested a 1-page handout of the RAC would be helpful for the learner when the module is being presented.

| 1=Totally Disagree |

2=Neutral | 3=Totally Agree |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The title clearly reflects the intent of the educational module |

|||

| 2. The purpose and intent of the educational module is clearly stated in the objectives. | |||

| 3. The contribution of the educational module to improved health care outcomes is evident. | |||

| 4. The rationale for the development of the educational module is evident. | |||

| 5. The methods used to inform bedside nurses how to read and understand research reports are introduced in the objectives of the educational module. |

|||

| 6. A description of the methods used to inform bedside nurses how to read and understand research reports is presented in sufficient detail that others could reproduce it. | |||

| 7. The research assessment checklist (RAC) is a method that will inform bedside nurses how to identify weaknesses and strengths of research. |

|||

| 8. Instructing bedside acute care nurses how to complete a literature review will increase their ability to read and understand research reports. | |||

| 9. Informing bedside acute care nurses how to create a table of evidence will improve their knowledge and skills of evidence-based practice. |

|||

| 10. The educational module will strengthen bedside acute care nurses’ ability to support their practice with current best evidence. |

For answers 1=Totally Disagree and 2=Neutral, please place comments below.

Table 1: Author-modified SQUIRE 2.0 checklist

A second and final theme expressed in the comments provided by the content experts focused on expanding the content of the module to inform viewers of the differences between quantitative and qualitative research. Suggestions included providing key points of how to critique quantitative and qualitative research reports. One expert suggested the module would work well as a two-part series. Part 1 could be titled How to Critique the Article, and Part 2 could include How to Organize and Pool Data. Another expert suggested the table of evidence (TOE) would benefit from including an extra column with a grading scale to identify the strength of research reports. The extra column at the end of the TOE would include the use of a scoring measure such as the John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model [11,12].

Discussion

Studies indicate most nurses do not have the knowledge and skills to appraise the literature that supports their clinical practice. When patient care is supported by current best evidence, patient outcomes improve and the cost of health care decreases [3,6,13]. This study was designed to investigate if the review of an EBP educational module by five subject matter experts (SMEs) would further strengthen the EBP content of the module. The module teaches nurses how to locate, identify, and categorize data in a way bedside acute care nurses can understand. The ability to view research reports in this manner offers nurses a means to identify strong versus weak research reports. If nurses are able to identify research reports that would provide evidence-based support for their clinical practice, patient outcomes will improve [4].

The five SMEs participating in this study work in academia and clinical practice. The experts included two Ph.D. prepared nurses working in academia for a total 49 years, two DNP prepared nurses working in clinical administration for a total of 27 years, and one DNP prepared nurse working in academia for a total of 8 years. Assessment of the educational module by the experts provided several considerations to enrich the EBP content of the educational module. The information provided by the experts was analyzed to determine whether the feedback suggested evidence-based methods to enhance the content of the educational module. The findings from the content experts provided feedback that will be used to enrich the EBP content of the educational module. Recommendations by the content experts identified principles presented in the module that needed clarifying. Discussion of the study results are organized into two themes that emerged from the study.

Methods used in the educational module are in detail, so others can duplicate

Two of the SMEs reviewing the educational module proposed adding more detail about the 51- question Research Assessment Checklist (RAC) the bedside nurses will use as a guide when critiquing a research report. Two additional slides with greater detail in the content of the RAC have been added to the 30-slide power point presentation module. Expanded information about the RAC in the form of a handout will be given to participants during the implementation of the educational module. One SME advised that if the teaching module was going to be used as a tool that is repeatable, a script for other presenters of the module needed to be crafted. Previous studies indicate proven effective methods to introduce EBP to bedside nurses have not yet been identified [2,3]. What has been identified in earlier studies indicates that when bedside nurses are able to read and understand research reports, their knowledge and understanding of EBP increases. When bedside nurses are able to access, read and identify rigorous studies, clinical practice is more often supported by EBP [3,4].

Expanded information of the methods of research

According to the SMEs’ review of the module, the hierarchy of evidence levels was well presented. Information of how to critique quantitative and qualitative research reports was suggested by one of the experts who is employed in clinical administration at an acute care facility. This SME also suggested adding a grading column to the TOE. The EBP content of the educational module has been expanded by adding a grading column to the TOE. The column, using the John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice Model, lists a level of evidence and a grading system for each article reviewed and placed in the TOE. With the ability to differentiate between different types of research articles, bedside nurses may benefit by knowing how studies differ and how to approach different types of research articles to support their clinical practice. A cross-sectional, descriptive online survey was used to determine to what extent RNs in an acute care multihospital system used research to support their practice. Although a variety of methods for locating research and implementing EBP was available, nurses cited the same barriers that have been reported over the past 20 years; lack of time, lack of knowledge, and lack of resources.

Nurses surveyed in this study expected hospital educators and advanced practice nurses to gather and synthesize research for them [14].

Study Implications

The findings from this study may serve to direct further inquiry into methods best suited to expand the ability of bedside acute care nurses to read and understand research reports. Future research needs to address the effectiveness of different methods and activities that will strengthen nurses’ knowledge and skills in understanding current best evidence [15]. When best methods for educating bedside nurses in how to read and understand research reports are identified, evidence will be generated to support the best strategies to support improved patient outcomes. Future research needs to take place to evaluate the reliability and generalizability of the methods identified that inform nurses how to appraise research to support their clinical practice and policymaking [16].

Strengths and Limitations

The academic qualifications of the sample were similar to what one might find worldwide in professional nurses with doctorate degrees in nursing. The primary limitation of the project was the small sample size of five content experts. A second limitation was the utilization of the author-modified SQUIRE 2.0 Checklist, which did not have proven reliability and validity. The SQUIRE 2.0 Checklist was modified to a shorter version because eight of the eighteen questions were not applicable as a guide for appraising the educational module. Methodological limitations of the modified SQUIRE 2.0 Checklist may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Also, the utilization of feedback from five content experts in one area of the country may not be generalizable to larger populations worldwide. Another limitation identified was that information was received from the content experts one time rather than collating the experts’ findings and returning it to them for concurrence again.

Conclusion

Results of this study revealed that the review by five subject matter experts (SME) of an EBP educational module designed to instruct bedside acute care nurses how to read and understand research reports, provided significant enhancement of the EBP content of the module. Moreover, further research is suggested to examine effective educational modalities used to instruct bedside acute care nurses how to read and understand research reports.

Acknowledgement

The author extends sincere gratitude to the industrious professional nurses who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- Hoffman T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the professions. Sydney, Australia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2012.

- Mollon D, Fields W, Gallo A, et al. Staff practice, attitudes and knowledge/skills regarding evidence-based practice before and after educational intervention. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2012;43:411-9.

- Stevens KR. The impact of evidence-based practice in nursing and the next big ideas. Online J Issues Nurs. 2012;18:1-13.

- Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Schultz A. Transforming health care from the inside out: Advancing evidence-based practice in the 21st century. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21:335-44.

- Bonner A, Sando J. Examining the knowledge, attitude and use of research by nurses. J Nurs Management. 2008;16:334-43.

- Heiwe S, Kajermo KN, Tyni-Lenne R, et al. Evidence-based practice: Attitude, knowledge and behavior among allied health professionals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:198-209.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 2001.

- Duffy ME. A Research appraisal checklist for evaluating nursing research reports. Nurs and Health Care. 1985;6:538-40.

- Levin R, Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, et al. Fostering evidence-based practice to improve nurse and constituent outcomes in a community health setting: A pilot test of the advancing research and clinical practice through close collaboration model. Nurs Admin Quarterly. 2011;35:21-33.

- http://squire-statement.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=471

- Newhouse RP, Dearholt SL, Poe SS, et al. Johns Hopkins Nursing; Evidence-based practice model and guidelines: Sigma Theta Tau International, Indianapolis. Nurs Educ Practice. 2009;9:4.

- https://www.nursingworld.org/organizational-programs/magnet

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Gallagher-Ford L, et al. The state of evidence-based practice in US nurses: critical implications for nurse leaders and educators. J Nurs Admin. 2012;42:410-7.

- Yoder L, Kirkley, McFall D, et al. CE: Original research staff nurses’ use of research to facilitate evidence-based practice. AJN. 2014;114:26-37.

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Putting research into practice; Reflections on nursing leadership. Sigma Theta Tau International, Honor Society of Nursing. 2002;28:22-5.

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams Wilkins. 2011.