Management of anticoagulation in rate controlled atrial fibrillation: A three-step approach

Received: 04-Jan-2017 Accepted Date: Feb 16, 2017; Published: 18-Feb-2017, DOI: 10.4172/2368-0512.1000079

Citation: Hoehmann CL, Gravina A, Cuoco JA. Management of anticoagulation in rate controlled atrial fibrillation: A three-step approach. Curr Res Cardiol 2017;4(1):1-4.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Atrial Fibrillation is the most common type of cardiac arrhythmia managed in clinical practice. This condition predisposes patients to a multitude of potential complications that can be managed or prevented by medical or surgical means. Such complications include stroke, hemorrhage, or heart failure, among others. Although surgical intervention may be a viable option in some cases, pharmacological rate-control is a less invasive and more robust method in preventing the genesis of these sequelae. However, current guidelines regarding pharmacologic control of atrial fibrillation sequelae may be difficult to interpret. Based upon clinical prediction rules derived from large-scale clinical trials, we provide a simple three-step sequential algorithm that clinicians may use as guidelines when managing patients with rate controlled atrial fibrillation. These protocols can help clinicians decide if anticoagulation medication is indicated (CHA2DS2-VASc score), select the appropriate agent for anticoagulation (SAMe-TT2R2 score), and anticipate a high risk of hemorrhage (HAS-BLED score).

Keywords

Anticoagulation, Atrial fibrillation, CHA2DS2-VASc score, SAMe- TT2R2 score, HAS-BLED score, Stroke

Abbreviations

AF: Atrial Fibrillation; VKA: Vitamin K Antagonist; TTR: Time in Therapeutic Range; INR: International Normalized Ratio; DOAC: Direct Acting Oral Anticoagulant

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common type of arrhythmia managed in clinical practice [1-3]. The impact of this disease is projected to increase as it has a predilection for the elderly population [3,4]. Atrial fibrillation is not a benign condition; rather, it significantly increases risk of heart failure, kidney disease, coronary artery disease, and most notably, stroke [2,5-7]. Furthermore, the annual projected financial burden of this disease to the health care system amounts between $6 to $26 billion dollars [7]. For such reasons, a systematic approach to properly manage AF is beneficial not only for patients, but also for the healthcare system as a whole.

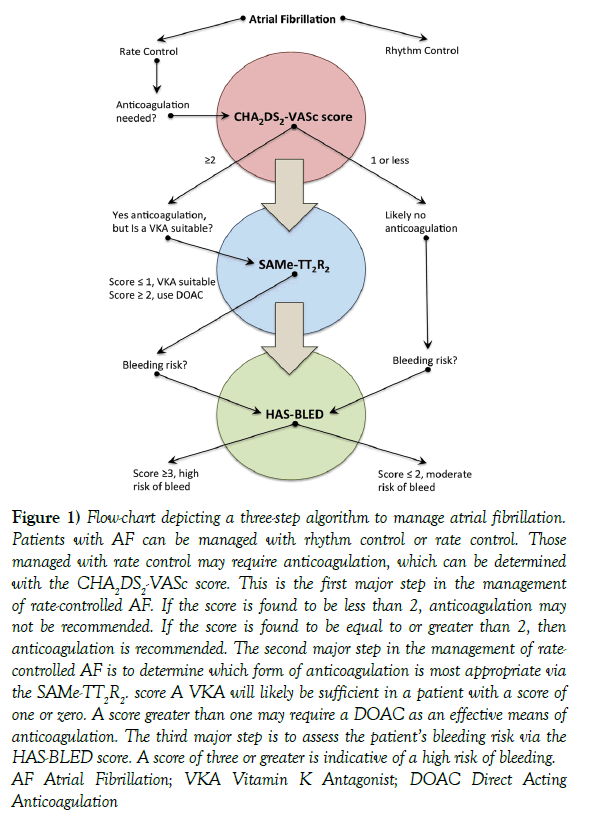

Although pharmacologic management of AF is essential to prevent sequelae, current guidelines for pharmacologic intervention may be difficult to interpret. Here, we provide a simple three-step sequential algorithm based on clinical prediction rules derived from large-scale clinical trials that clinicians may use as simplified guidelines when managing patients with AF. These protocols can help clinicians decide if anticoagulation medication is indicated (CHA2DS2-VASc score), select the appropriate agent for anticoagulation (SAMe-TT2R2 score), and anticipate a high risk of hemorrhage (HAS-BLED score) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow-chart depicting a three-step algorithm to manage atrial fibrillation. Patients with AF can be managed with rhythm control or rate control. Those managed with rate control may require anticoagulation, which can be determined with the CHA2DS2-VASc score. This is the first major step in the management of rate-controlled AF. If the score is found to be less than 2, anticoagulation may not be recommended. If the score is found to be equal to or greater than 2, then anticoagulation is recommended. The second major step in the management of ratecontrolled AF is to determine which form of anticoagulation is most appropriate via the SAMe-TT2R2. score A VKA will likely be sufficient in a patient with a score of one or zero. A score greater than one may require a DOAC as an effective means of anticoagulation. The third major step is to assess the patient’s bleeding risk via the HAS-BLED score. A score of three or greater is indicative of a high risk of bleeding. AF Atrial Fibrillation; VKA Vitamin K Antagonist; DOAC Direct Acting Anticoagulation

Rate control versus rhythm control

In the management of AF, a clinician must select to use either rhythm control or rate control [8]. Cardioversion, a form of rhythm control, is the act of restoring an irregular heartbeat to a sinus rhythm by electrical or chemical means [9]. This method is of highest utility if it is used early in disease progression [9]. Radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation, additional forms of rhythm control, are best suited for young individuals without structural heart disease or for those who are intolerant to or refractory to antiarrhythmic medications [10,11].

Rate control is considered to be the cornerstone in the management of AF [12]. Heart rate control can be achieved pharmacologically with medications that block conduction at the atrioventricular node, decreasing the quantity of electrical pulses transmitted to the ventricles [12]. Such medications include beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and less commonly, cardiac glycosides [12]. The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) trial, which addressed whether rate control and anticoagulation are acceptable objectives for asymptomatic elderly patients, determined that rhythm control provided no survival advantage over rate control and anticoagulation [13]. The Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) trial demonstrated similar findings [14]. Thus, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2006 guidelines state that rate control is a “reasonable” strategy for managing AF [8,15].

CHA2DS2-VASc score

AF can cause blood stasis secondary to uncoordinated atrial muscle contraction in the upper chambers of the heart. Non-synchronous atrial contraction predisposes to mural thrombus formation, which can dislodge causing a stroke [16]. This process can be mitigated with the use of anticoagulation medication; however, due to an increased risk of hemorrhage, anticoagulation therapy is not indicated for all patients [8]. The CHA2DS2-VASc score was developed to help identify which patients may benefit from anticoagulation therapy (Table 1).

Condition |

Points |

|

|---|---|---|

C H A2 D S2 V A Sc |

Congestive heart failure (or left ventricular systolic dysfunction) Hypertension: blood pressure consistently above 140/90 mmHg (or treated hypertension on medication) Age ≥75 years Diabetes Mellitus Prior Stroke, thromboembolism, or TIA Vascular Disease (PAD, MI, aortic plaque) Age 65-74 years Sex category (i.e. female sex) |

1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 |

Each letter corresponds to a stroke risk modifier in the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Any individual with a total score of at least two points should be recommended oral anticoagulation therapy. A male with a total score of one should be considered for oral anticoagulation. A male with a total score of zero, or a female with a total score of zero or one should not be recommended oral anti-coagulation.

Table 1: CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system

Further research by Esteve-Pastor et al. validated the score as an effective means of identifying patients requiring anticoagulation [17]. A patient with a higher score is more likely to suffer a stroke [18] (Table 2).

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | Annual Stroke Risk % |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1.3 |

| 2 | 2.2 |

| 3 | 3.2 |

| 4 | 4.0 |

| 5 | 6.7 |

| 6 | 9.8 |

| 7 | 9.6 |

| 8 | 12.5 |

| 9 | 12.2 |

A patient in rate controlled atrial fibrillation with a higher total CHA2DS2-VASc score is more likely to suffer a stroke (25).

Table 2: Correlation of CHA2DS2-VASc score and annual stroke risk

The CHA2DS2-VASc score has shown additional utility in other areas as well. Recent research by Mlodawska et al. suggests the score may be used to predict unsuccessful electrical cardioversion [19]. Other recent research by Saliba et al. suggests the score may be useful when calculating a patient’s risk for stroke in patients without AF and that the score may also be used to detect the likelihood of new-onset AF [20,21].

The CHA2DS2-VASc score has superseded the similar CHADS2 score. An investigation of the Central Registry of the German Competence NETwork on Atrial Fibrillation (AFNET) registry, which included 8,847 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, found the CHA2DS2-VASc score to be more sensitive than the CHADS2 score for risk stratification of thromboembolic events [22]. Furthermore, according to the Assessment of Cardioversion Using Transesophageal Echocardiography (ACUTE) trial sub study, the CHA2DS2-VASc score was found to be more reliable in predicting left atrial appendage thrombus formation, especially in those with a low or intermediate risk score [23].

When considering oral anticoagulation therapy, there are a number of options available. The disadvantage of the CHA2DS2-VASc score is that it cannot suggest which oral anticoagulant is appropriate for each individual. Therefore, the SAMe-TT2R2 score may be utilized for this purpose.

SAMe-TT2R2 score

A number of options exist for anticoagulation in rate-controlled non-valvular AF. Oral anticoagulation can be achieved with a Vitamin K antagonist (VKA), such as warfarin, with greater than 70% time in the therapeutic range (TTR) and an international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0-3.0 [24,25]. Recent research has shown the newer direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC), such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and apixaban, to be effective as well [24]. SAMe-TT2R2 may be used as a tool to help the clinician decide whether to use a VKA or DOAC in order to anticoagulate a patient in rate-controlled AF [24-27] (Table 3).

| Condition / Influencing Factor | Points |

|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 1 |

| Age (60 years) | 1 |

| Medical History (two of the following: HTN, DM, MI, PAD, CHF, stroke, and pulmonary, hepatic, or renal disease) | 1 |

| Treatment (interacting medications – amiodarone) | 1 |

| Tobacco use (within 2 years) | 2 |

| Race (non-Caucasian) | 2 |

The SAMe-TT2R2 score constitutes a variety of factors or conditions that can influence TTR. A score of zero or one is likely to achieve greater than 65% in TTR and is therefore suitable for VKA therapy, such as warfarin (24). A score of two or greater is not likely to meet this criteria and is not suitable for VKA therapy. In this scenario, DOAC therapy may be initiated along with education for the patient regarding anticoagulation control [24]. HTN Hypertension; DM Diabetes mellitus; MI Myocardial infarction; PAD Peripheral arterial disease; CHF Congestive heart Failure; TTR Time in therapeutic range; VKA Vitamin K antagonist; DOAC Direct acting anticoagulation

Table 3: SAMe-TT2R2 scoring system

Additionally, clinicians should also consider patient preferences and comorbities, including bleeding risk, renal function, and interaction with other medications [24].

The function of the SAMe-TT2R2 score is to predict the quality of VKA as measured in the TTR [25,26]. Thus, the score can identify which patients will not perform well with a VKA, as they will not reach the adequate TTR [25]. For these patients, a DOAC may be recommended in place of a VKA [25]. However, only the use of a VKA may be recommended when treating AF in the context of rheumatic mitral valve disease or a mechanical heart valve prosthesis [8,15].

Although DOAC medications have been shown to be effective, they have certain impediments [24]. With a VKA such as warfarin, it is possible to evaluate the TTR by monitoring the INR; currently, there is no such lab value available to monitor the TTR of DOAC medications [24,25]. Furthermore, unlike VKA medications such as warfarin, which can be reversed with Vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma, many of the DOAC medications currently do not have approved reversal medications. As such, investigational research is underway to identify mechanisms to monitor DOAC therapeutic levels. Moreover, reversal agents have been identified for many DOAC medications, such as idarucizumab for dabigatran, andexanet alfa for factor Xa inhibitors, and ciraparantag as a universal reversal agent [25,28].

HAS-BLED score

Patients with rate controlled AF are at increased risk of hemorrhage secondary to the use of anticoagulation therapy. Therefore, an assessment of bleeding risk is indicated. The HAS-BLED score, derived via data collected from 3,978 patients in the Euro Heart Survey, was developed in order to assess one-year risk of major bleeding in patients with AF [29] (Table 4).

Condition |

Points |

|

|---|---|---|

H A S B L E D |

Hypertension: (uncontrolled, >160 mmHg systolic) Abnormal renal function: Dialysis, transplant, Cr >2.26 mg/dL or >200 µmol/L Stroke: Prior history of stroke Bleeding: Prior major bleeding or predisposition to bleeding Labile INR: (Unstable/ high INRs), TTR <60% Elderly: Age >65 years Prior alcohol or Drug use history (≥ 8 drinks/week) |

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 |

The HAS-BLED scoring system constitutes a number of conditions placing a patient with atrial fibrillation at a higher risk for major bleeding. A score of three or greater indicates a patient to be at “high-risk” for major bleeding within the next year [30]. That patient must then be addressed with increased caution, regular review, and education [30]. Cr Creatinine; AST Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT Alanine aminotransferase; AP Alkaline phosphatase; INR International normalized ratio; TTR Time in therapeutic range; NSAID Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Table 4: HAS-BLED scoring system

In this instance, a major bleeding event is defined as intracranial bleeding, hospitalization, a decrease in hemoglobin greater than 2 grams per deciliter, or requiring a blood transfusion [30].

In addition to the HAS-BLED score, there are multiple clinical prediction rules for the purpose of assessing bleeding risk in those with AF, such as the HEMORR2HAGES score, Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment (ORBIT) score, and also the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) score [31]. However, the HAS-BLED score has outperformed all of these other scores in largescale clinical trials [31-33]. This is likely due to inclusion of the criterion of labile international normalized ratios by the HAS-BLED score, which is not included in other similar risk scores [31,33]. Furthermore, the HAS-BLED score was applied to a population of 9,621 patients with AF taking rivaroxaban and was successful in its ability to predict major bleeding [34].

Conclusion

Herein, we have illustrated a simple algorithm using clinical prediction rules determined by large-scale clinical trials that clinicians may follow when managing patients with AF. Using these guidelines, a clinician can know when to use anticoagulation, how to choose the appropriate method of anticoagulation, and when to anticipate a high risk of major hemorrhage.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Michael Casey for his knowledge, guidance, and wisdom in preparing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: National implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: The anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA 2001;285:2370-75.

- O'Neal WT, Efird JT, Judd SE, et al. Impact of awareness and patterns of nonhospitalized atrial fibrillation on the risk of mortality: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Clin Cardiol 2016;39:103-10.

- Chugh S, Blackshear J, Shen W, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2001;37:371–78.

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The framingham study. Stroke 1991;22:983-88.

- Soliman EZ, Safford MM, Muntner P, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:107-14.

- O'Neal WT, Qureshi W, Zhang ZM, et al. Bidirectional association between atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2016;17:181-86.

- Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu BC, et al. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:313-20.

- 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:e1-e88.

- Boriani G1, Diemberger I, Biffi M, et al. Pharmacological cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: current management and treatment options. Drugs 2004;64:2741-62.

- Georgiopoulos G, Tsiachris D, Manolis AS. Cryoballoon ablation of atrial fibrillation: a practical and effective approach. Clin Cardiol 2016.

- Kyprianou K, Pericleous A, Stavrou A, et al. Surgical perspectives in the management of atrial fibrillation. World J Cardiol 201626;8:1-15.

- Van Gelder I, Rienstra M, Crijns J, et al. Rate control in atrial fibrillation. The Lancet 2016;388:818-10.

- Wyse DG, Waldo AL, Di Marco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1825-33.

- Hagens VE, Ranchor AV, Van Sonderen E, et al. Effect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:241-47.

- Fuster V, Rydn LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for practice guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257-97.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Rothbart RM, et al. Stroke with intermittent atrial fibrillation: incidence and predictors during aspirin therapy. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:183-85.

- Esteve-Pastor MA, Marín F, Bertomeu-Martinez V, et al. Do physicians correctly calculate thromboembolic risk scores? A comparison of concordance between manual and computer-based calculation of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2 -VASc scores. Intern Med J 2016;46:583-89.

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. "Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation". JAMA 2001;285:2864-70.

- Mlodawska E, Tomaszuk-Kazberuk A, Lopatowska P, et al. CHA2 DS2 VASc score predicts unsuccessful electrical cardioversion in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Intern Med J 2016.

- Saliba W, Gronich N, Barnett-Griness O, et al. The role of CHADS2 and CHA2 DS2 -VASc scores in the prediction of stroke in individuals without atrial fibrillation: A population-based study. 2016;14:1155-62.

- Saliba W, Gronich N, Barnett-Griness O, et al. Usefulness of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in the prediction of new-onset atrial fibrillation: A population-based study. Am J Med. 2016;129:843-49.

- Gerth A, Nabauer M, Oeff M, et al. Stroke events in patients with CHADS2 scores 0 and 1 in a contemporary population of patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the German AFNET registry. Eur Heart J 2013;34:808-11

- Yarmohammadi H, Varr BC, Puwanant S, et al. Role of CHADS2 score in evaluation of thromboembolic risk and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing direct current cardioversion (from the ACUTE Trial Substudy). Am J Cardiol 2012;110:222-26.

- Amin A. Choosing non-Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: practical considerations we need to know. Ochsner J 2016;16:531-10.

- Proietti M, Lip YHG. Simple decision-making between a vitamin K antagonist and a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant: using the SAMe-TT2R2 score. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy 2015;1:150-52.

- Bernaitis N, Ching CK, Chen L, et al. The sex, age, medical history, treatment, tobacco use, race risk (SAMe TT2R2) score predicts warfarin control in a singaporean population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc 2017;26:64-6.

- Ruiz-Ortiz M, Bertomeu V, Cequier Á, et al. Validation of the SAMe-TT2R2 score in a nationwide population of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients on vitamin K antagonists. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2015;114:695-97.

- Shih AW, Crowther MA. Reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: a practical approach. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016;2016:612-18.

- Kaithoju S. Ischemic stroke: Risk stratification, warfarin teatment and outcome measure. J Atr Fibrillation 2015;8:1144.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat, R, et al. "A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation". Chest 2010;138:1093-100.

- Senoo K, Proietti M, Lane DA, et al. Evaluation of the HAS-BLED, ATRIA, and ORBIT Bleeding Risk Scores in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Taking Warfarin. Am J Med 2016;129:600-07.

- Fauchier L, Chaize G, Gaudin AF, et al. Predictive ability of HAS-BLED, HEMORR2HAGES, and ATRIA bleeding risk scores in patients with atrial fibrillation. A french nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiol 2016;217:85-7

- Caldeira D, Costa J, Fernandes RM, et al. Performance of the HAS-BLED high bleeding-risk category, compared to ATRIA and HEMORR2HAGES in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2014;40:277-84.

- Gorman EW, Perkel D, Dennis D, et al. Validation of the HAS-BLED tool in atrial fibrillation patients receiving rivaroxaban. J Atr Fibrillation 2016;9:146.