Mentoring the clinical nurse in nursing research

Received: 20-Mar-2018 Accepted Date: Mar 28, 2018; Published: 10-Apr-2018

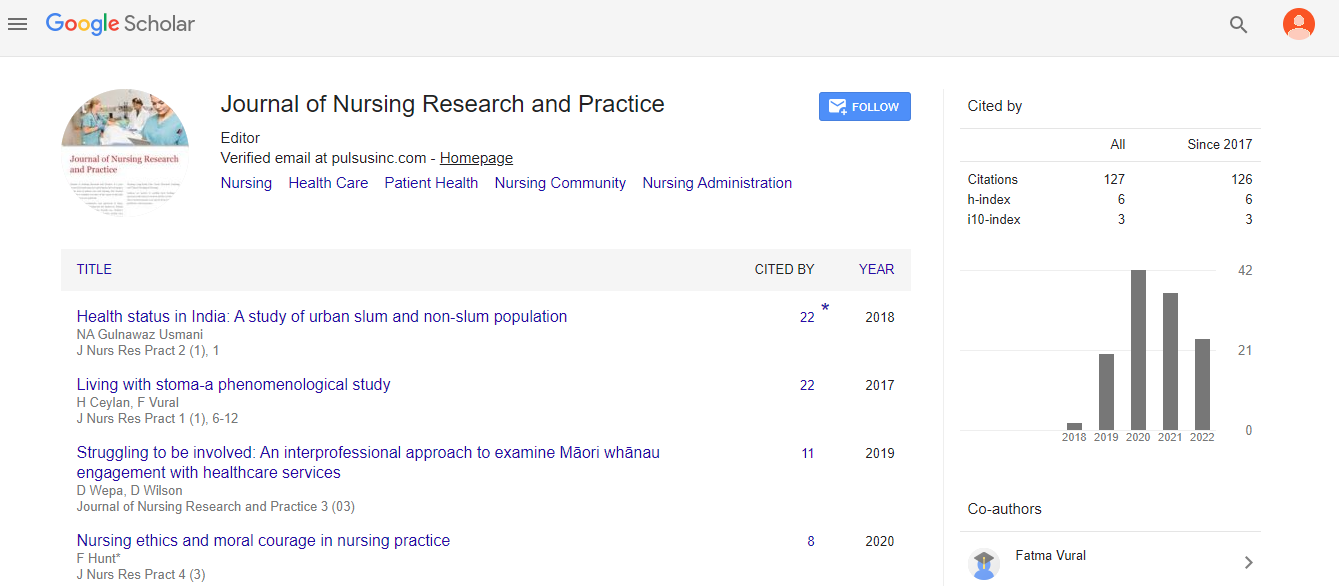

Citation: Washington GT. Mentoring the clinical nurse in nursing research. J Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2(2):13-15.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to describe the research mentoring process used with a small team of nurses by a PhD prepared nurse certified as a Nursing Professional Development Specialist and as a Critical Care Clinical Nurse Specialist. It will describe how bedside nurses were actively engaged in the research process by having them learn about research while operationalizing that knowledge as simultaneously were mentored in conducting a relevant research study. The process described and discussed in this article should be useful to nurse leaders to facilitate removing the traditional barriers to nursing research that still remain in healthcare organizations today. These include lack of time and knowledge, about the process, lack of institutional support, and lack of mentoring through the process. It should also be helpful to nurse educators in the clinical area to encourage more nurses to participate in nursing research.

Keywords

Mentoring; Nursing research; Research barriers

Introduction

Why is it important for nurses at the bedside to engage in nursing research? Clinical nursing research is a very important part of nursing practice and bedside nurses are in the best position to generate those relevant clinical questions that will improve the state of the science of nursing. It is essential for nursing care activities and interventions to be based in science to provide the most safe, effective, and efficient care possible to patients and clients receiving that care. The Institute of Medicine and the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Magnet® recognition program both recognize that importance and encourage the use of evidence-based practice in the care of patients [1]. The challenge has been in overcoming those traditional barriers to both conducting research and to the integration of results in to the current workflow and culture. The purpose of this article is to describe the process used to overcome these challenges.

This process took place in a health care organization with a nursing research council as part of the shared governance structure for approximately 20 years. The council operated primarily at the flagship hospital of the organization’s 14 facilities. During this time, there had been varying levels of interest and activity related to the actual conduct and use of nursing research results. Past research topics included restricted versus open ICUs [2], visitor and nurse satisfaction with visiting hours [3], cough CPR [4], Continual Lateral Rotational Therapy [5], and Family Advocate Programs [6]. At the time of this mentored research study, the research council was chaired by a PhD prepared nurse certified as a Critical Care Clinical Nurse Specialist and as a Nursing Professional Development Specialist with research experience.

The reasons expressed by staff nurses at this organization for the lack of research at this organization were the same as those found in the literature; lack of time, mentors, experience and institutional support [7-9]. Because of these traditional barriers, there were no active nursing research studies in progress at the time of this mentored activity. Those few that had been conducted in the past were completed with the Critical Care Clinical Specialists, Critical Care Educators, and faculty from the local university’s College of Nursing. There was no formal nursing research mentoring program in place, but because the literature suggests that mentoring is very important in moving nursing research forward, the CCNS continued to mentor the nurses in the research study after transferring from the acute care area to the education and training department [10,11].

The idea of a mentored research study developed when a recently graduated BSN staff nurse attended a Magnet® conference after her organization became the first in the state to receive that designation. The Magnet® conference presentation involved changing peripheral IV sites based on assessment and nursing judgment rather than hospital policy of every 96 hours [12].

Since she had some research experience in her college of nursing’s honors in discipline (HID) program, she was interested in attempting to replicate a study presented during the conference. The HID concept is just one of many methods school and colleges of nursing are employing to facilitate students’ interest in research [13]. During the student’s HID experience, she had access to faculty, research assistance, a statistician, and a research librarian to facilitate her research study. She brought the idea to the research council, but those historical barriers in her clinical practice environment prevented her from getting started. The staff nurse declined to continue with the project, so the PhD research council chair brought the proposal to the nursing practice council and offered to serve as mentor for the research study. They determined that the concept of the presentation, changing IV sites based on nursing judgement, was relative to the organization’s practice and gave unanimous support to the mentored research study.

Developing the Infrastructure

The research mentor determined that the process would consist of three areas: institutional support, research education and training, and mentorship. Concentration on these areas would remove several historical barriers to bedside nurses being involved in or conducting original research. One of the nurse managers on the practice council recommended offering nurses participating in the organization’s clinical ladder program an opportunity to participate in the study. These nurses had already demonstrated interest in professional development and would be more likely to volunteer to participate.

The research mentor emailed invitations to a list of Registered Nurses and Licensed Practical Nurses participating in the organization’s clinical ladders program. The invitation included an outline of the background, purpose, and proposed study question to assist in their consideration of participation in the process. An initial group of 10 nurses expressed interest, but several factors prohibited seven from participating. After hearing the proposed plan, the first work meeting consisted of two BSN prepared RNs, one LPN to BSN student, and the PhD research mentor. This team collaborated for a period of 18 months to complete the education and the study.

Institutional support

Institutional support commenced when the nurse managers on the practice council recommended soliciting a team from those participating in the clinical ladders program. With the team in place, discussion and collaboration with their nurse managers led to an agreement to provide two hours per month paid work time to prepare for and conduct the research, as well as manuscript preparation for publication. Although these managers removed the barriers of time and institutional support for these nurses, they did not realize the limited work time would prolong the completion of the study. Even after being made aware of that potential, they still only allowed for two hours per month paid time for the team. The team still considered this action as an improvement in support for nursing research.

As a testament to the team’s professionalism, we often met for longer than two hours partly just to do the work, and partly because the team was really interested in each session. The team maintained an audit trail document as a record of decisions made, rationale for actions taken, and as a record of time spent if requested by the managers. We even included any time over the agreed upon two-hour limit.

Institutional support was also evident with the agreement of the organization’s Learning Resource Center (medical library) to allow the team to meet there in the evenings. This agreement facilitated computer access as well as an open environment to conduct the research education and training without interruption from or interruptions to other users.

Mentoring

The primary goal for this activity was mentoring these nurses through the research process, using a question that was relevant to their nursing practice. Achieving this goal would provide the experience to help demystify nursing research, and improve patient and nurse satisfaction, patient comfort, and reduce material costs. The second goal was to complete the research process and submit a manuscript for publication describing our research questions and results for dissemination to the nursing community [14].

As one of the historical barriers to bedside nurses participating in original research, mentoring was a necessary component of this process. A research leader is key to promoting nursing research in an organization, and clinical nurses participating in research are more successful when they have an identified mentor [9,11]. Therefore, the research mentor would be the individual who would be with the team for the duration of the study, guiding them through each step educationally and practically.

Research education and training

The first team meeting consisted of an informal needs assessment to determine individual and group knowledge about research and the process. This was necessary to make a plan going forward regarding the content needed as well as how to deliver the education and training. One of the BSN nurses had participated in a research study before but wanted to go through this process more for the education. The other BSN nurse had no prior experience with research at all. The LPN to BSN student had just started her program and had not had any research education or experience. She did not want to miss the opportunity to “get ahead” with that aspect of her program.

The mentor used what the literature calls “just in time” education, to engage the team in learning about each step of the research process rather than present that information all at one time [15,16]. The plan was to study about a step in the process, then do that step in the research study. These steps included drafting the initial question, identifying the subjects, conducting a literature search, refining the question, determining the study design and sample size, data collection tool(s) and data collection, data analysis and interpretation, application of the interpreted results, study limitations and suggestions for future research, and dissemination. The team was actively engaged because we discussed and learned concepts and then applied those concepts throughout the research study.

The team engaged in active learning as the mentor facilitated their learning about research rather than providing didactic, classroom lectures [17]. They were about to become active participants in an original research study. Increased awareness of the research process began as early as conducting the informal needs assessment, which outlined the steps, thereby already increasing knowledge as we talked through the assessment.

Process Delivery

Learning began with each team member’s commitment to completing the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) course as required. Prior to registering for the CITI course, each team member conducted a search about the course and the reason for its requirement prior to any human subject research. They also conducted a search on Institutional Review Boards (IRB) to gain appreciation for the need for that body, as well as identifying the IRB to which we would be submitting our research proposal.

As we met in the library for each session, each team member had access to her own individual computer. We would conduct literature searches on our topic of interest and read those theoretical and research articles with several goals in mind. First, we would read to determine what literature we needed to read more closely to assist us in refining our question. Then we read the appropriate literature to identify the state of the science to further determine if our question was relevant to others in nursing. We used the literature to assist with finding a tool for data inclusion and collection, or as we finally did, constructing our own tool.

Based on the literature, we had brainstorming sessions on how to efficiently and effectively collect the data. We also used research texts to discuss the different study designs and statistical procedures. We then use the literature to see how the designs were implemented and how the procedures were used, and whether both were used appropriately. As we asked questions of the data collected in our study and decided on the answers, reading the literature helped to determine how to interpret the data after analysis, and identify the presence and the effects of any study limitations.

During data collection, we had opportunity to engage master’s prepared nurses as data collectors. Having multiple data collectors gave us the opportunity to explore interrater reliability as we reviewed both the tool and the process with them. This was to ensure that the data collectors were approaching and collecting data in the same manner for each subject patient.

As we concocted the study, we spent considerable time with journal articles and texts related to our question as well as the research process. We experienced data collecting from both the medical records and patients, and conversations with the IRB regarding research application and required revisions. We discovered the importance of planning for data entry in ways that would facilitate data analysis and interpretation. This would all make it possible to better draw accurate and appropriate conclusions from the results.

Reading research articles spurred one team member to accept the challenge to co-author the manuscript of the research results for submission to a nursing journal. Together the team member and the research mentor reviewed the steps of the research process and mirrored those steps throughout the manuscript. We found that the audit trail notes were helpful in developing the manuscript.

The one team member also stated that writing the manuscript also helped her to understand the process even more. She also stated that the publication process had been very mysterious to her and now she had a much better idea of what it takes for publication. She really appreciated publication when we were searching the literature for background information and data collection tools. This led to her realization that this research study and the resulting manuscript could be used in another researcher’s literature search and was very excited to see her name in print [18], as well as gain knowledge about evidence-based practice in nursing [19]. This was also an opportunity to engage her particular nurse manager in the process by continuing to receive paid time to contribute to the manuscript development.

Implications for Nursing

This was real world experience in research for this team and an education for their managers as well. It helped the managers to experience the process through the granting of paid time, and that they were instrumental in removing historical barriers. It also prompted the thought that perhaps if given more that than two hours per month it may have taken less than 18 months to complete the study. Using our audit trail notes, the team members were able to explain the process and length of time to their managers.

As this study came to completion, it was also useful in demonstrating the importance of publication and dissemination of research results. Preparing a manuscript allowed us to review the steps of the research process again, with that process being a learning tool. We engaged other nurses by acknowledging the publication with the bedside nurse as second author to her nurse manager as well as to the research, practice, and quality councils. The facility’s Chief Nursing Officer also acknowledged her accomplishment to her peer groups.

Finally, we demonstrated the successful incorporation of nursing research into the workflow of the bedside nurse, particularly with the aid of a mentor or sponsor. The support of the nurse managers was instrumental in the completion of this study and a demonstration of institutional support. It was educational for nurses as they participated and observed research in action. It provided results that were meaningful to the organization’s particular patient population, which was useful in planning for a more specific review of practice.

REFERENCES

- Hatfield LA, Kutney-Lee A, Halloweil SG, et al. Fostering Clinical Nursing Research in a Hospital Context. J Nurs Adm 2016;46:245-9.

- Ramsey P, Cathelyn J, Gugliotta B, et al. Restricted versus Open ICUs. Nurs Manage 2000;31:42-4.

- Ramsey P, Cathelyn J, Gugliotta B, et al. Visitor and nurse satisfaction with a visitation policy change in critical care units. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 1999;18:42-8.

- Eorgan PA, Greer JL. Cough CPR: a consideration for high-risk cardiac patient discharge teaching. Crit Care Nurs 1992;12:21-7.

- Washington GT, Macnee LC. Evaluation of outcomes: The Effects of Continuous lateral Rotational Therapy. J Nurs Care Qual 2005;20:273-82.

- Washington GT. Family advocates: caring for families in crisis. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2001;20:35-40.

- Burnett M, Lewis M, Joy, et al. Participating in clinical nursing research: challenges and solutions of the bedside nurse champion. Medsurd Nurs 2012;12:309-11.

- McLaughlin MK, Speroni KG, Kelly KP, et al. National survey of hospital nursing research, part 1. J Nurs Adm 2013;43:10-17.

- Scala E, Price C, Day J. An integrative review of engaging clinical nurses in nursing research. J Nurs Scholarsh 2016;48:423-10.

- Kelly KP, Turner A, Speroni KG. National survey of hospital nursing research, part 2. J Nurs Adm 2013;43:18-23.

- Gettrust L, Hagle M, Boaz L, et al. Engaging nursing staff in research. Clin Nurse Spec 2016:30;203-7.

- Gallant P, Schultz A. Evaluation of a visual infusion phlebitis scale for determining appropriate discontinuation of peripheral intravenous catheters. J Infus Nurs 2006:29;338-45.

- Jansen DA, Jadack RA, Ayoola AB, et al. Embedding research in undergraduate learning opportunities. West J Nurs Res 2015;37:1340-58.

- Kooker BM, Latimer R, Mark DD. Successfully coaching nursing staff to publish outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2015;45:636-41.

- Black AT, Balneaves LG, Garossino C. Promoting Evidence-Based Practice Through a Research Training Program for Point-of-Care Clinicians. J Nurs Adm 2015;1:14-20.

- Berger J, Polivka B. Advancing Nursing Research in Hospitals Through Collaboration, Empowerment, and Mentoring. J Nurs Adm 2015;12:600-5.

- Johnson HA, Barrett LC. Your teaching strategy matters: how engagement impact application in health information literacy instruction. J Med Libr Assoc 2017;105:44-8.

- Washington GT, Barrett R. Peripheral phlebitis: a point-prevalence study. J Infus Nurs 2012;34:252-8.

- Newhouse RP, Dearholt SL, Poe SS, et al. Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines. IN: Sigma Theta Tau International; Indianapolis.