Therapeutic approaches to the promotion of anabolism in aging men

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Richard Bebb

Suite 416, 1033 Davie Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6E 1M7

Tel: 604-689-1055

Fax: 604-689-2955

E-mail: rabebb@interchange.ubc.ca

Keywords

Diet; Growth promoting factors; Hormonal replacement therapy; Human growth hormone; Insulin-like growth factor-1; Muscle mass; Physical exercise; Quality of life; Sexual life; Steroids

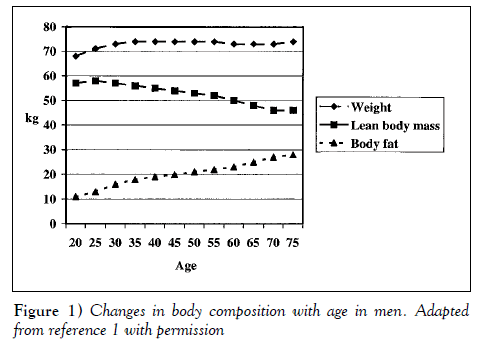

Advancing age brings with it an associated decrease in muscle mass [1] and strength, and a decrease in bone mineral density with an increased risk of fracture [2]. These changes in lean body mass are seen together with an increase in percentage of body fat (Figure 1) [1]. Hence, consideration of one tissue type in isolation is perhaps unrealistic and, further, may not reveal the full clinical impact of changes in body composition. The present article explores the available evidence for the promotion of anabolism in aging men.

While many people strive to maintain a youthful appearance – indeed, some age-related body changes are perhaps more cosmetic than medical in nature – it is clear that marked changes in body composition are associated with an adverse clinical outcome [3]. Decreased lean body mass reflects a decrease in muscle bulk and bone density [2]. Muscle loss or sarcopenia leads to decreased mobility, decreased enjoyment of life, and an increased risk of falling and disability in elderly individuals [4,5]. Low bone density in older men is associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, resulting in increased mortality risk [2]. The flip side of lean body mass changes is an increase in percentage of body fat with aging [1]. This body fat increase is, in part, an increase in visceral fat, with an adverse effect on lipid and glucose metabolism, and an increased risk of vascular disease [3].

It would be desirable to minimize or, if possible, reverse the above morphological changes of aging. Interventions that increase lean body mass and/or decrease the percentage of body fat can potentially decrease the incidence of diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerotic disease and hypertension [3].

Interventions may include dietary change; regular exercise; detection and aggressive treatment of chronic disease; supplementation with androgenic compounds such as testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) or androstenedione; growth hormone supplementation; or any combination of these modalities.

Dietary therapy for the promotion and maintenance of anabolism should include a well balanced diet with sufficient calories for maintenance [6]. Specific nutrients should include calcium supplementation, to ensure intake of 1000 to 1500 mg of elemental calcium per day. Vitamin D intake should be between 400 and 800 IU per day.

Claims that supplements such as creatine or chromium picolinate are beneficial for body composition are unsubstantiated [7]. Alcohol intake should be minimized [8]. Excessive alcohol can promote catabolism, perhaps through lowering serum testosterone levels or, in the case of bone density, a direct toxic effect on bone [2,8].

Regular exercise is a key factor in the promotion of anabolism [6,7]. Regular exercise can increase muscle bulk and strength, decrease percentage of body fat and increase bone mineral density [7]. In conjunction with a healthy diet, regular exercise should be regarded as the cornerstone of therapy.

It is well known that chronic disease can lower both testosterone and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 levels. One study matched cohorts of chronically ill and well older men and showed a 10% lower level of testosterone in the former group [9]. Detection and optimum treatment of chronic disease should include attention to the maintenance of nutrition, exercise, and the minimization of drugs that promote catabolism, such as corticosteroids, or that interfere with the androgen or growth hormone-IGF-1 axes. A special note should be made about sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is more common in men than women, and incidence increases with advancing age. Untreated sleep apnea can lower serum testosterone levels and, potentially, IGF-1 levels as well.

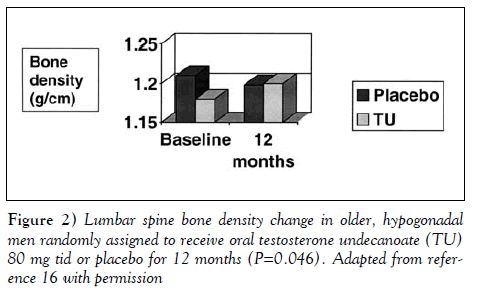

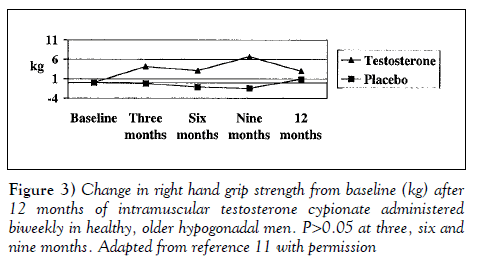

Androgens have well established anabolic effects on muscle and bone [10]. In elderly hypogonadal men, testosterone administration positively affects biochemical markers of muscle and bone metabolism [10]. Testosterone administration in hypogonadal aging men has been shown to improve body composition in double-blind, placebo controlled studies that have included oral, transdermal and intramuscular forms of testosterone [11-15]. A number of these studies have also shown an increase in lumbar spinal bone density (Figure 2) [11,13,15,16]. The functional status of muscles, as assessed by grip or quadriceps strength, improved in some studies ( Figure 3) [10,11,15]. Whether these positive effects on muscle and bone lessen the age-related risk of falls and osteoporotic fracture awaits further study.

Other androgen-like compounds, such as DHEA and androstenedone, have engendered much controversy in both the medical and lay press. DHEA has shown some promise in both increasing lean body mass and decreasing the percentage of body fat in men [17,18]. Unfortunately, not all studies yielded positive changes in body composition [19]. It is unclear how these effects of DHEA are accomplished. Due to the lack of any conclusive data identifying a DHEA receptor in the body, it may be that DHEA exerts its effects only when converted to other steroid hormones such as testosterone or estradiol.

Androstenedione is another testosterone precursor that, unlike DHEA, does have some inherent, weak anabolic action. Although a highly publicized study did not show any effect on body composition, testosterone levels did not increase in male subjects taking androstenedione, and hence, the dose was probably insufficient [20]. Despite the lack of conclusive studies, if sufficient androstenedione is administered to produce an physiological increase in serum testosterone, an anabolic effect is expected [21].

The gradual decline in serum levels of androgens is not unique. Growth hormone and IGF-1 levels also decline significantly in many aging men and women [22]. Growth hormone administration has been studied both in patients with pituitary disease and in those with an age-related decrease in androgen serum levels [23-26]. There is a synergistic interaction between the growth hormone and the androgen axis [24]. It is known that estrogens can increase growth hormone levels, and hence, the administration of an aromatizable androgen can increase growth hormone and IGF-1 levels [24]. Growth hormone is thought to suppress sex hormone-binding globulin, and therefore, growth hormone administration in aging men may increase free or bioavailable testosterone. These physiological interactions may be a potential explanation for the overlap in the clinical effect seen in studies of growth hormone and testosterone administration [24].

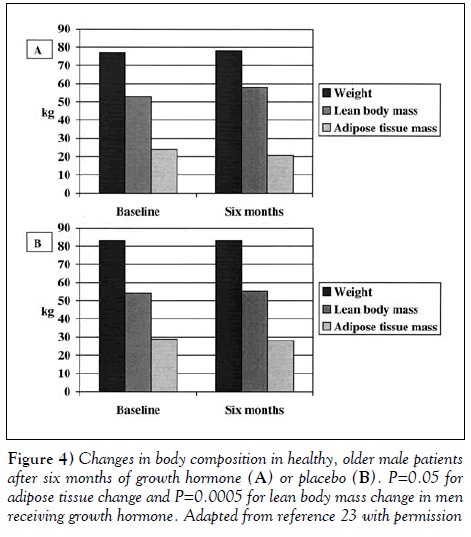

Growth hormone supplementation has been shown to increase lean body mass and bone density while decreasing body fat (Figure 4) [23,25,26]. Despite the increase in muscle bulk, an improvement in muscle strength is not universal [26]. No data exist with regard to long term fracture risk. The therapeutic use of growth hormone has been hampered by its high cost and the need for daily subcutaneous injections of the hormone. Research is progressing in the development of orally active growth hormone secretogagues.

Although IGF-1 can also be given subcutaneously and, theoretically, could be used as an anabolic agent, it is no longer under active development due to side effects seen in studies to date.

Conclusions

Changes in body composition seen with advancing age have significant associated adverse medical outcomes. Preliminary evidence suggests that anabolic agents, such as testosterone and growth hormone, have promising effects on age-related sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Larger, long term studies are needed to investigate more fully the benefits and potential risks of these anabolic agents as they relate to the treatment of osteoporosis, vascular disease and agerelated disability.

Testosterone and growth hormone have beneficial anabolic effects on muscle and bone in aging men. These hormones have the potential to limit age-related atrophy of these tissues, and to improve the quality of life and maintenance of independence in aging men.

References

- Forbes GB, Reina JC. Adult lean body mass declines with age: some longitudinal observations. Metabolism 1970;19:653-63.

- Cooper C, Melton LJ 3rd. Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1992;3:224-9.

- Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, Bird AP, Oster G. Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2177-83.

- Holloszy JO. Workshop on sarcopenia: muscle atrophy in old age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A:1-161.

- Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:755-63.

- Fielding RA. The role of progressive resistance training and nutrition in the preservation of lean body mass in the elderly. J Am Coll Nutr 1995;14:587-94.

- Campbell WW, Joseph LJO, Davey SL, Cyr-Campbell D, Anderson RA, Evans WJ. Effects of resistance training and chromium picolinate on body composition and skeletal muscle in older men. J Appl Physiol 1999;86:29-39.

- Persky H, O’Brien CP, Fine E, Howard WJ, Khan MA, Beck RW. The effect of alcohol and smoking on testosterone function and aggression in chronic alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:621-5.

- Gray A, Feldman HA, McKinley JB, Longcope C. Age, disease, and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men: results of the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;73:1016-25.

- Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Gilkison C, et al. Testosterone administration to elderly men increases skeletal muscle strength and protein synthesis. Am J Physiol 1995;269:E820-6.

- Sih R, Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM, Patrick P, Ross C. Testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a 12 month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:1661-7.

- Tenover JS. Effects of testosterone supplementation in the aging male. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:1092-8. 13.Tenover JS. Testosterone for all? Proceedings of the 80th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. New Orleans, June 24 to 27, 1998.

- Tenover JS. Testosterone for all? Proceedings of the 80th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. New Orleans, June 24 to 27, 1998.

- Hajjar RR, Kaiser FE, Morley JE. Outcomes of long-term testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3793-6.

- Snyder PJ, Peachy H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on bone density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1966-72.

- Bebb RA, Anawalt BD, Wade JP, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of testsoterone undecanoate administration in aging hypogonadal men: effects on bone density and body composition. Proceedings of the 83th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. Denver, June 20 to 23, 2001.

- Morales AJ, Haubrich RH, Hwang JY, Asakura H, Yen SSC. The effect of six months treatment with 100 mg daily dose of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on circulating sex steroids, body composition and muscle strength in age-advanced men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1998;49:421-32.

- Yen S, Morales A, Khorram O. Replacement of DHEA in aging men and women; potential remedial effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;774:128-42.

- Flynn MA, Weaver-Osterholtz D, Sharpe-Timms KL, Allen S, Krause G. Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in aging humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1527-33.

- King DS, Sharp RL, Vukovich MD, et al. Effect of oral androstenedione on serum testosterone and adaptations to resistance training in young men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;281:2020-8.

- Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N et al. The effects of supraphysiological doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in men. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1-7.

- Carpas E, Harman SM, Blackman MR. Human growth hormone and human aging. Endosc Rev 1993;14:20-39.

- Rudman D, Feller AG, Nagraj HS, et al. Effects of human growth hormone in men over 60 years old. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1-6.

- Ivey FM, Herman SM, Hurley BF, et al. Effects of HG and/or sex-steroid administration on thigh muscle and fat by magnetic resonance imaging in healthy elderly men and women. Proceedings of the 81th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. San Diego, June 12 to 15, 1999.

- Jorgensen JO, Thuesen L, Miller J, Ovesen P, Shakkebaek NE, Christiansen JS. Three years of growth hormone treatment in growth hormone deficient adults: near normalization of body composition and physical performance. Eur J Endocrinol 1994;130:224-8.

- Papadakis MA, Grady D, Black D, et al. Growth hormone replacement in healthy older men improves body composition but not functional ability. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:708-16.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Richard Bebb

Suite 416, 1033 Davie Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6E 1M7

Tel: 604-689-1055

Fax: 604-689-2955

E-mail: rabebb@interchange.ubc.ca

Abstract

It is clear that the marked changes in body composition that occur with aging are associated with an adverse clinical outcome. Decreased lean body mass reflects a decrease in muscle bulk and bone density. Muscle loss or sarcopenia leads to decreased mobility, decreased enjoyment of life, and an increased risk of falling and disability in elderly individuals. Low bone density in older men is associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, resulting in increased mortality risk. The flip side of lean body mass changes is an increase in the percentage of body fat with aging. This body fat increase is, in part, an increase in visceral fat, with an adverse effect on lipid and glucose metabolism, and an increased risk of vascular disease. It would be desirable to minimize or, if possible, reverse the above morphological changes of aging. Interventions that increase lean body mass and/or decrease the percentage of body fat can potentially decrease the incidence of diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerotic disease and hypertension. The present article explores the available evidence for the promotion of anabolism in aging men.

-Keywords

Diet; Growth promoting factors; Hormonal replacement therapy; Human growth hormone; Insulin-like growth factor-1; Muscle mass; Physical exercise; Quality of life; Sexual life; Steroids

Advancing age brings with it an associated decrease in muscle mass [1] and strength, and a decrease in bone mineral density with an increased risk of fracture [2]. These changes in lean body mass are seen together with an increase in percentage of body fat (Figure 1) [1]. Hence, consideration of one tissue type in isolation is perhaps unrealistic and, further, may not reveal the full clinical impact of changes in body composition. The present article explores the available evidence for the promotion of anabolism in aging men.

While many people strive to maintain a youthful appearance – indeed, some age-related body changes are perhaps more cosmetic than medical in nature – it is clear that marked changes in body composition are associated with an adverse clinical outcome [3]. Decreased lean body mass reflects a decrease in muscle bulk and bone density [2]. Muscle loss or sarcopenia leads to decreased mobility, decreased enjoyment of life, and an increased risk of falling and disability in elderly individuals [4,5]. Low bone density in older men is associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, resulting in increased mortality risk [2]. The flip side of lean body mass changes is an increase in percentage of body fat with aging [1]. This body fat increase is, in part, an increase in visceral fat, with an adverse effect on lipid and glucose metabolism, and an increased risk of vascular disease [3].

It would be desirable to minimize or, if possible, reverse the above morphological changes of aging. Interventions that increase lean body mass and/or decrease the percentage of body fat can potentially decrease the incidence of diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerotic disease and hypertension [3].

Interventions may include dietary change; regular exercise; detection and aggressive treatment of chronic disease; supplementation with androgenic compounds such as testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) or androstenedione; growth hormone supplementation; or any combination of these modalities.

Dietary therapy for the promotion and maintenance of anabolism should include a well balanced diet with sufficient calories for maintenance [6]. Specific nutrients should include calcium supplementation, to ensure intake of 1000 to 1500 mg of elemental calcium per day. Vitamin D intake should be between 400 and 800 IU per day.

Claims that supplements such as creatine or chromium picolinate are beneficial for body composition are unsubstantiated [7]. Alcohol intake should be minimized [8]. Excessive alcohol can promote catabolism, perhaps through lowering serum testosterone levels or, in the case of bone density, a direct toxic effect on bone [2,8].

Regular exercise is a key factor in the promotion of anabolism [6,7]. Regular exercise can increase muscle bulk and strength, decrease percentage of body fat and increase bone mineral density [7]. In conjunction with a healthy diet, regular exercise should be regarded as the cornerstone of therapy.

It is well known that chronic disease can lower both testosterone and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 levels. One study matched cohorts of chronically ill and well older men and showed a 10% lower level of testosterone in the former group [9]. Detection and optimum treatment of chronic disease should include attention to the maintenance of nutrition, exercise, and the minimization of drugs that promote catabolism, such as corticosteroids, or that interfere with the androgen or growth hormone-IGF-1 axes. A special note should be made about sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is more common in men than women, and incidence increases with advancing age. Untreated sleep apnea can lower serum testosterone levels and, potentially, IGF-1 levels as well.

Androgens have well established anabolic effects on muscle and bone [10]. In elderly hypogonadal men, testosterone administration positively affects biochemical markers of muscle and bone metabolism [10]. Testosterone administration in hypogonadal aging men has been shown to improve body composition in double-blind, placebo controlled studies that have included oral, transdermal and intramuscular forms of testosterone [11-15]. A number of these studies have also shown an increase in lumbar spinal bone density (Figure 2) [11,13,15,16]. The functional status of muscles, as assessed by grip or quadriceps strength, improved in some studies ( Figure 3) [10,11,15]. Whether these positive effects on muscle and bone lessen the age-related risk of falls and osteoporotic fracture awaits further study.

Other androgen-like compounds, such as DHEA and androstenedone, have engendered much controversy in both the medical and lay press. DHEA has shown some promise in both increasing lean body mass and decreasing the percentage of body fat in men [17,18]. Unfortunately, not all studies yielded positive changes in body composition [19]. It is unclear how these effects of DHEA are accomplished. Due to the lack of any conclusive data identifying a DHEA receptor in the body, it may be that DHEA exerts its effects only when converted to other steroid hormones such as testosterone or estradiol.

Androstenedione is another testosterone precursor that, unlike DHEA, does have some inherent, weak anabolic action. Although a highly publicized study did not show any effect on body composition, testosterone levels did not increase in male subjects taking androstenedione, and hence, the dose was probably insufficient [20]. Despite the lack of conclusive studies, if sufficient androstenedione is administered to produce an physiological increase in serum testosterone, an anabolic effect is expected [21].

The gradual decline in serum levels of androgens is not unique. Growth hormone and IGF-1 levels also decline significantly in many aging men and women [22]. Growth hormone administration has been studied both in patients with pituitary disease and in those with an age-related decrease in androgen serum levels [23-26]. There is a synergistic interaction between the growth hormone and the androgen axis [24]. It is known that estrogens can increase growth hormone levels, and hence, the administration of an aromatizable androgen can increase growth hormone and IGF-1 levels [24]. Growth hormone is thought to suppress sex hormone-binding globulin, and therefore, growth hormone administration in aging men may increase free or bioavailable testosterone. These physiological interactions may be a potential explanation for the overlap in the clinical effect seen in studies of growth hormone and testosterone administration [24].

Growth hormone supplementation has been shown to increase lean body mass and bone density while decreasing body fat (Figure 4) [23,25,26]. Despite the increase in muscle bulk, an improvement in muscle strength is not universal [26]. No data exist with regard to long term fracture risk. The therapeutic use of growth hormone has been hampered by its high cost and the need for daily subcutaneous injections of the hormone. Research is progressing in the development of orally active growth hormone secretogagues.

Figure 4: Changes in body composition in healthy, older male patients after six months of growth hormone (A) or placebo (B). P=0.05 for adipose tissue change and P=0.0005 for lean body mass change in men receiving growth hormone. Adapted from reference 23 with permission

Although IGF-1 can also be given subcutaneously and, theoretically, could be used as an anabolic agent, it is no longer under active development due to side effects seen in studies to date.

Conclusions

Changes in body composition seen with advancing age have significant associated adverse medical outcomes. Preliminary evidence suggests that anabolic agents, such as testosterone and growth hormone, have promising effects on age-related sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Larger, long term studies are needed to investigate more fully the benefits and potential risks of these anabolic agents as they relate to the treatment of osteoporosis, vascular disease and agerelated disability.

Testosterone and growth hormone have beneficial anabolic effects on muscle and bone in aging men. These hormones have the potential to limit age-related atrophy of these tissues, and to improve the quality of life and maintenance of independence in aging men.

References

- Forbes GB, Reina JC. Adult lean body mass declines with age: some longitudinal observations. Metabolism 1970;19:653-63.

- Cooper C, Melton LJ 3rd. Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1992;3:224-9.

- Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, Bird AP, Oster G. Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2177-83.

- Holloszy JO. Workshop on sarcopenia: muscle atrophy in old age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A:1-161.

- Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:755-63.

- Fielding RA. The role of progressive resistance training and nutrition in the preservation of lean body mass in the elderly. J Am Coll Nutr 1995;14:587-94.

- Campbell WW, Joseph LJO, Davey SL, Cyr-Campbell D, Anderson RA, Evans WJ. Effects of resistance training and chromium picolinate on body composition and skeletal muscle in older men. J Appl Physiol 1999;86:29-39.

- Persky H, O’Brien CP, Fine E, Howard WJ, Khan MA, Beck RW. The effect of alcohol and smoking on testosterone function and aggression in chronic alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:621-5.

- Gray A, Feldman HA, McKinley JB, Longcope C. Age, disease, and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men: results of the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;73:1016-25.

- Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Gilkison C, et al. Testosterone administration to elderly men increases skeletal muscle strength and protein synthesis. Am J Physiol 1995;269:E820-6.

- Sih R, Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM, Patrick P, Ross C. Testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a 12 month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:1661-7.

- Tenover JS. Effects of testosterone supplementation in the aging male. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:1092-8. 13.Tenover JS. Testosterone for all? Proceedings of the 80th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. New Orleans, June 24 to 27, 1998.

- Tenover JS. Testosterone for all? Proceedings of the 80th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. New Orleans, June 24 to 27, 1998.

- Hajjar RR, Kaiser FE, Morley JE. Outcomes of long-term testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3793-6.

- Snyder PJ, Peachy H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on bone density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1966-72.

- Bebb RA, Anawalt BD, Wade JP, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of testsoterone undecanoate administration in aging hypogonadal men: effects on bone density and body composition. Proceedings of the 83th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. Denver, June 20 to 23, 2001.

- Morales AJ, Haubrich RH, Hwang JY, Asakura H, Yen SSC. The effect of six months treatment with 100 mg daily dose of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on circulating sex steroids, body composition and muscle strength in age-advanced men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1998;49:421-32.

- Yen S, Morales A, Khorram O. Replacement of DHEA in aging men and women; potential remedial effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;774:128-42.

- Flynn MA, Weaver-Osterholtz D, Sharpe-Timms KL, Allen S, Krause G. Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in aging humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1527-33.

- King DS, Sharp RL, Vukovich MD, et al. Effect of oral androstenedione on serum testosterone and adaptations to resistance training in young men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;281:2020-8.

- Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N et al. The effects of supraphysiological doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in men. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1-7.

- Carpas E, Harman SM, Blackman MR. Human growth hormone and human aging. Endosc Rev 1993;14:20-39.

- Rudman D, Feller AG, Nagraj HS, et al. Effects of human growth hormone in men over 60 years old. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1-6.

- Ivey FM, Herman SM, Hurley BF, et al. Effects of HG and/or sex-steroid administration on thigh muscle and fat by magnetic resonance imaging in healthy elderly men and women. Proceedings of the 81th Meeting of the Endocrine Society. San Diego, June 12 to 15, 1999.

- Jorgensen JO, Thuesen L, Miller J, Ovesen P, Shakkebaek NE, Christiansen JS. Three years of growth hormone treatment in growth hormone deficient adults: near normalization of body composition and physical performance. Eur J Endocrinol 1994;130:224-8.

- Papadakis MA, Grady D, Black D, et al. Growth hormone replacement in healthy older men improves body composition but not functional ability. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:708-16.