Awareness among medical and nursing units: Ethical and social aspects of organ donation from a living donor based on altruistic motives in Israel

2 Department of Nursing Sciences, Tel Aviv-Jaffa Academic College, Jaffa, Israel, Email: riadab@mta.ac.il

Received: 08-May-2018 Accepted Date: May 24, 2018; Published: 01-Jun-2018

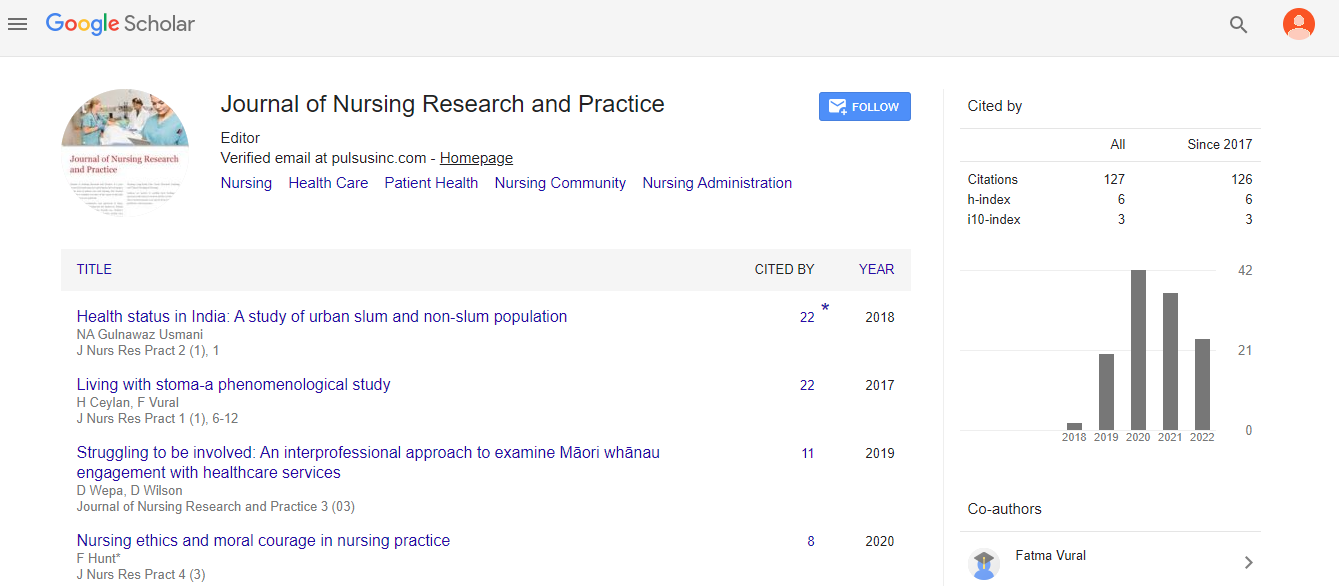

Citation: Tarabeih M, Awawdi K, Rakia RA. Awareness among medical and nursing units: Ethical and social aspects of organ donation from a living donor based on altruistic motives in Israel. J Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2(3):8-12.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objectives: The authors of the present study were doubtful as to whether the risks attached to live kidney donation had been sufficiently assessed and protected against. The aim of the present study was to examine the rigorousness and safety of the current live donation process in Israel.

Background: From 2015-2017, 65% of all kidney donations in Israel were live donations.

Methods: The authors surveyed 91 Israelis who had donated a kidney. The questionnaire asked about the content of the pre-donation process, if and how the risks had been explained to donors, post-donation illness/ complications and the medical follow-up. Also, whether the donors felt supported, confident and well-advised.

Results: Creatinine levels rose significantly post-donation, and highest in the youngest 18-29) donor age group. None of the donors were followed-up by a nephrologist, but by their GP only, and none had more than 2 follow-up checks. None was referred to a nephrologist for treatment or monitoring despite the raised creatinine levels. The risk information the donors received also reveals gaps and inadequacies.

Conclusions: The authors propose recommendations to make the live donation process, more rigorous, more cautious, better followed-up and more strongly research-based. Equally important is to take vigorous action to multiply the number of deceased donations. Each deceased donation means one less live donation and so the less harm to healthy persons.

Keywords

Live kidney; Donation; Nephrology; Donor risk; Uninephrectomy

Introduction

By early 2018 almost seven thousand Israeli were on dialysis of whom 1,138 were waiting for a transplant [1]. 840 of these were on the waiting list for a kidney transplant, when the average waiting time in Israel is six years, three times as long as the waiting period in Europe. Israel has the lowest rate of deceased donations of 21 developed nations [2]. Only 35% of kidneys for transplant came from deceased donations and the deceased donation rate is hardly rising. No more than 14% of the adult population in Israel has signed the National Transplant Centre (NTC) card indicating agreement to deceased organ donation [3].

As for live kidney donations, the rates are rising worldwide: they constitute about 30% of all kidney donations in the UK, 5-10% in the USA, and about 50% in Norway [4,5]. In Israel, in the three years 2015-2017, of the total of 816 kidney donations 65% were live donations [6]. About two-thirds of the live donations were the work of one voluntary association active, set up in 2009 and working almost exclusively among ultra-orthodox Jews to persuade them to donate a kidney. It is responsible to date for some 500 live donations and, without it, the waiting list for a kidney transplant in Israel would be that much longer.

Live kidney donation in Israel began essentially in 2008 when the Israeli parliament legislated an array of benefits for live donors—reimbursement of monetary outlays entailed by the donation, reimbursement of lost work-days and earning capacity, three years’ exemption from the national healthcare tax, reimbursement of outlays on life insurance and short-term psychotherapy, seven days convalescence and travel up to a determined sum. In addition, all signatories to the NTC card and their family members would themselves receive priority should they ever need a transplant [7]. None of the above rewards was large enough in money terms to constitute a temptation to donate an organ to make money.

The Israel Ministry of Health (MOH) regulates live organ donations [8]. It differentiates between two types of donations:

• Persons wishing to donate to a family member (sibling, parent, spouse/civil partner, grandparent, uncle/aunt or cousin) are interviewed by the locally appointed transplant assessment board of any licenced hospital and this board may authorise the donation.

• Persons wishing to donate to a non-family-member must undergo a more extensive and more probing process— independent of the transplant process—involving psychosocial, psychological and psychiatric assessments before they are finally interviewed by the Ministry of Health-appointed Central Assessment Board, which, after also interviewing the intended organ recipient, may authorize or reject the proposed live donation. The process of medical testing, the various assessments and interview by the Board can last from 2-6 months.

This board is chaired by a senior nephrologist and its four other members must include a second medical specialist, a psychologist or psychiatrist, a social worker, and a legal professional, none of whom may be employed by/ part of the national organ transplant system. Their job is to interview both the potential donor and the recipient: they must verify that the donation is done of the donor’s free will, not subject to pressure from their or the recipient’s family, or to financial or other pressure. They must verify that both donor and recipient have received comprehensive explanations about the donation and transplant process, have understood this information and its significance, and that the motivation for the donation is altruistic and does not involve any material remuneration. They must ensure that both donor and recipient are psycho-socially suitable for the donation process. They will inform the donor that he or she can change their mind at any time.

All donors, both family and non-family, before meeting with their assessment board will have been examined by a nephrologist at the National Transplantation Centre, as well as by a cardiologist, cardiovascular specialist, and gastroenterologist. The nephrologist will have tested for blood type, kidney function (chiefly creatinine and protein urine level) and blood pressure. There will also be a CT angiography of the kidney blood vessels and laboratory tests for kidney, liver and pancreatic function.

The Ministry of Health regulations state that all live donors should undergo long-term annual follow-up checks (by the transplant hospital or the donor’s GP and comprising at least urine and blood pressure tests and a kidney ultrasound examination). It is the donor’s responsibility to arrange these checks.

The 2008 legislation had some success but not nearly enough. In particular the need for kidney transplants has accelerated over the last decade with the increase of the numbers of patients on dialysis. As a result of the persistent severe shortage of organs for transplant there is pressure on the Knesset (parliament) to follow the lead of the 24 European countries which, as of 2010, have legislated some form of presumed consent to donate (an opt-out system).

The current realities of live kidney donation are a controversial issue. Although worldwide the rates of live kidney donation are rising often it is not clear why. Both legislation and ethical norms in most western countries forbid payment for organ donation but the suspicion is in many cases that hidden and unethical practices are at work, that somehow money is being exchanged and, to some extent at least, the poor are being exploited. Israel is not exempt from this. Like other countries where paying for organs is prohibited some material compensation is allowed, as set out above. It is also the case, however, that Israeli health management organizations (HMOs) will compensate members who travel abroad for a kidney transplant for 70% of their outlay since this will cost them much less than funding years of dialysis in Israel. In principle they reimburse their members only for transplants of a deceased donation, but the problem is that many obtain a live donation transplant and then return to Israel with false documentation affirming that the transplanted organ was a deceased donation. Thus, in effect, Israeli HMOs are funding the many dubious live donation systems known to operate in the Third World.

A second issue still under debate is the risk attached to live kidney donation. By the early years of the 21st century the level of risk attached to live donation seemed to be small. The death rate of live donors on the operating table was about 0.03%. Immediate complications occurred in 1-10% of cases [9]. As for later complications, a summary of 48 research studies found that some donors suffered an immediate reduction in their glomerular filtration rate which sorted itself out in time, and that the only other adverse effect was a slight rise in blood pressure [10]. Live organ donations were found to be very successfully accepted by the recipient’s body, with a very high survival rate. Even in cases where there was no genetic relationship between donor and recipient live donation transplants were statistically more successful than deceased kidney transplants [11-13]. However, there were also contrary findings. At least two reports described donors in the United States who were subsequently placed on the waiting list for kidney transplantation [11,14].

These latter negative findings (among others) prompted a very large and methodologically very thorough study which has seemed to confirm the optimistic estimation of the level risk attached to live kidney donation [15]. The Hassan study (a) measured the vital status and lifetime risk of endstage renal disease (ESRD) in 3,698 Americans who donated kidneys from 1963 through 2007, and (b) from 2003 through 2007 it also measured the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and urinary albumin excretion and assessed the prevalence of hypertension, general health status, and quality of life in 255 donors. The conclusions of this very comprehensive study were that survival rates and the risk of ESRD in carefully screened kidney donors appeared to be similar to those in the general population. Most donors in the second sample had a preserved GFR, normal albumin excretion, their rates of albuminuria and hypertension were similar to those of matched controls, and they reported an excellent quality of life. Hypertension and diabetes (the two most common causes of kidney disease) developed at a similar frequency among donors as in the general population.

Recently, moreover, surgical techniques have advanced to make it possible to remove kidneys from live donors by laparoscopy, which reduces the risks involved compared to open surgery under general anesthetic, as well as shortening the convalescence period.

Despite this pervading optimistic assessment of the long-term risk attached to live kidney donation, the authors of the present study remain doubtful as to whether this risk has been sufficiently examined, assessed and protected against. The Hassan study, while exceptionally comprehensive of its kind, was not a longitudinal study that followed donors through from donation to old age. The present authors retain doubt as to whether all official protocols are observed in practice, whether all ethical issues have been settled, and whether an effort to increase deceased donations might not offer a preferable route forward. Deciding that their doubts were cogent, they made it their aim to re-examine the process of live kidney donation in Israel by questioning persons who had actually donated a kidney.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey study of a small research population—Israelis who had made a live kidney donation, both family donors and non-family donors.

Tool

The two-part questionnaire deployed in the present study was composed and validated by a group of seven very experienced transplant coordinators. The first part focused on the live donors’ sociodemographic and socioeconomic background. The second part covered the donation process itself and the risks it might carry. Was the process properly explained and understood, was the donor under any pressure, was the entire process properly conducted. Finally, it asked questions pertaining to the donor’s mental/ emotional state: did they feel supported and well-advised by the relevant bodies? What was their relationship with their own and the recipient’s family? (See Appendix A for the full questionnaire).

Research process

The sample of past live donors was assembled by two means: (a) The questionnaire—formatted into a Google Form—was distributed on social media (e.g. Facebook), smartphones, email and the websites of relevant associations in order to reach as many live organ donors as possible. 62 donors self-completed the questionnaire and returned it to us. (b) Knowing of the large contribution to live donation made by the Matat Khaim (Gift of Life) association we asked them to refer us to their donors. Researchers interviewed 39 donors face to face using IPads as almost no ultra-orthodox Jews use social media. (c) 8 donors from the Palestinian Authority area, who came to Israeli hospitals to donate to family members, were also interviewed in person.

Data gathering lasted 20 months, from 4.2016 to 12.2017. We experienced no language barriers, as all participants knew sufficient Hebrew to read and understand the questionnaire.

The sample

Of the 109 persons who completed and returned the questionnaire 18 were disqualified for incomplete or wrongly-completed questionnaires, resulting in a final sample of 91. See Table 1 for the composition of the final sample.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| male | 60 | 66 |

| female | 31 | 34 |

| Age at Donation | ||

| 18-29 | 13 | 14 |

| 30-39 | 39 | 43 |

| 40-49 | 39 | 43 |

| Schooling | ||

| up to 12 years | 41 | 45 |

| academic | 50 | 55 |

| marital status | 21 | 23 |

| Single/Divorced | ||

| married | 70 | 77 |

| religion | ||

| moslem | 13 | 14 |

| christian | 5 | 5 |

| jew | 73 | 81 |

| Religious Observance | ||

| secular | 8 | 9 |

| atheist | 14 | 15 |

| traditional | 32 | 35 |

| ultra-orthodox | 37 | 41 |

Table 1: Sample distribution (N=91)

The sample represents the population of live kidney donors in Israel fairly accurately. Jews are over-represented compared to the composition of the general population because, so few Israeli-Arabs are live donors. Men and ultra-orthodox Jews are over-represented compared to the general population because the abovementioned efforts of the Matat Khaim association among ultra-orthodox Jews generated mostly male donors.

Results and Discussion

Results

59% of the sample donated to a family member (similar to the proportion of all live kidney donors in Israel in recent years), 33% donated from religious or spiritual motives, 5.5% did it for the financial reward, and 2.2% because of having read or heard about the idea of live organ donation in the media, as shown in Table 2.

| Were you explained how your life would proceed with only one kidney? | |

| Yes | 87 |

| No | 13 |

| How were the pre-op tests conducted? | |

| Efficiently and quickly | 85 |

| With considerable waste of time | 15 |

| Did you meet with a psychiatrist, psychologist and social worker before the procedure? | |

| Psychiatrist, psychologist and social worker | 23 |

| Psychologist and social worker | 77 |

| Were you explained that because of the donation there was a risk of you developing kidney failure, hypertension or proteinuria? | |

| Yes | 80 |

| No | 20 |

| If this was explained to you, by whom? | |

| Nephrologist only | 14 |

| Nephrologist and transplant surgeon | 86 |

| Did you develop any illness after the donation? | |

| Yes | 25 |

| No | 75 |

| If you did, which illness? | |

| Hypertension | 12 |

| Proteinuria | 5 |

| Hypertension and proteinuria | 5 |

| Were you explained where your post-op follow-up testing would take place? | |

| Yes | 100 |

| No | 0 |

| If yes, which doctor conducted your follow-up? | |

| My GP | 100 |

| How many times did you visit your GP for a follow-up check? | |

| Once | 81 |

| Twice | 19 |

| Were you explained that the function level of the remaining kidney might rise to above normal levels? | |

| Yes | 23 |

| No | 77 |

| What was your kidney creatinine level before the donation? | |

| 0.6-0.8 | 67 |

| 0.81-1.2 | 33 |

| What was your kidney creatinine level after the donation? | |

| 0.6-0.8 | 48 |

| 0.81-1.2 | 37 |

| 1.21-1.5 | 14 |

| Were you explained which of your kidneys would be taken? | |

| Yes | 84 |

| No | 16 |

| If this was explained to you. Was the reason for the choice explained? | |

| Yes | 100 |

| No | 0 |

| Which kidney was removed, the left or the right? | |

| Left | 80 |

| Right | 20 |

Table 2: The donation processes

At their compulsory pre-donation medical examination all donors had normal renal function, as measured by their creatinine level. At the compulsory follow-up check 12 months later a paired-samples T test showed that creatinine levels had risen significantly. 51%, had a higher creatinine level, signifying reduced kidney function. 14% had a creatinine level of 1.2 or higher, which means--for someone with one kidney--that they should have been referred to a nephrologist for treatment or at least monitoring, but none were. A post hoc Tukey test showed that the post-donation creatinine rise was highest in the youngest [18-29] age group (M=0.297) and statistically significantly higher than for the 40-49 age group (M=0.122).

As for the further duration and quality of the medical follow-up, 81% of donors had only a single follow-up examination and none more than two. None of the donors were followed-up by a nephrologist. All were seen by their GP only, this when many GPs do not have the training to appreciate the significance of nephrological symptoms. follow-up examinations. The consequence of this less-than-complete follow-up was that within a year or two of their donation donors had lost contact with the nephrological care system and that they would only return to it when a symptom had become serious enough to alarm them back to the healthcare system. Ministry of Health regulations, we have seen, make the donor themself responsible for arranging all follow-up checks.

The information donors received also reveals inadequacies. Only 76% were told which kidney they were going to lose, and only 15% were explained why the left would be chosen (80% of the donors had their stronger left kidney removed). They were not told that the left kidney is the bigger and more effective one, and that the remaining right kidney might grow beyond its normal dimensions after the operation, due to its increased workload. 20% were not told of the risk of their developing kidney failure, hypertension or proteinuria, and in the event 22 of the 91 (24%) did develop a post-donation illness or complication. The indications of the present study are that live donors do not appear to receive sufficiently comprehensive information about the possible consequences to themselves of their donation.

In answer to the question: ‘Did the doctor who persuaded you to donate a kidney stay with you for the post-donation follow-up?’ the mean response was a low 1.16 (out of 5). Similarly, in answer to the question: ‘To what extent was your follow-up carried out as it was explained to you before the donation?’ the mean response was a low 1.33.

Discussion

This discussion falls into roughly three sections. First a consideration of the whether the risk to live kidney donors is greater than is customarily thought. Second, whether the live donation process in Israel (and perhaps elsewhere) takes adequate precautions against this risk. Third, the basic ethics of live donation.

The risk

Assessing organ donors is a complex calculation, yet the data available to assessors are limited. In particular, they do not have enough data regarding donors’ long- term health and their family medical history. What of the more medically-complex live donors? Do medical teams perform a sufficiently thorough anamnesis of the donor’s genetic background? Should they remove a kidney from a donor whose parents are diabetic or suffer from high blood pressure, making the donor more likely to develop these conditions at a later age, with the resultant increased strain on their one remaining kidney? The great majority of live donors are under forty and like most younger people prepared to take a risk which their medical advisors, relying on the majority consensus of currently available long-term studies, tell them is small. But it is in their middle and old age that their personal and family genetic baggage will make itself felt. The long-term consequences of donating a kidney are simply not fully understood. Whereas most data points to donors experiencing normal post-operative renal function, with blood pressure and urine protein-levels comparable to that of the general population (within their age group) and some research studies have found no impact on the lifespan of the donors, other studies point to the nephrectomy (kidney removal) contributing to a moderate rise in urine-protein and higher blood pressure [16-19].

The authors recommend conducting regular and long-term follow-ups on all live donors, in order to better pin down the risks to post-donation health. We also strongly support conducting thorough, long-term longitudinal studies of the long-term health of live donors.

It is not possible to make the criteria for donor exclusion entirely comprehensive. This makes it doubly important that the donor assessment process makes use of all available data and as many parameters as possible. We recommend that transplant teams be particularly strict when assessing them, and always prefer healthy older donors. We should bear in mind that the Hassan study quoted earlier found that a younger age at the time of donation was associated with a greater compensatory increase in the estimated GFR in the remaining kidney. “Uninephrectomy is followed by a compensatory increase in the GFR in the remaining kidney to about 70% of prenephrectomy values. We found that this compensatory increase was higher in donors who were younger at the time of donation”.

The two kidneys are not identical in size and form: the left being larger and, more importantly, functioning better than the right. Most surgeons chose to take the left kidney from a live donor, as it has a longer renal vain and so is easier to transplant. The general opinion is that the transplant of kidney allografts with shorter renal veins is more technically challenging and involves more vascular post-operative complications. The incidence of renal vein thrombosis, renal artery thrombosis, and renal artery stenosis due to anastomosis can complicate the transplant and jeopardize the transplanted kidney in the long and short term, and result in a much shorter half-life than average [20]. A study conducted by Justo-Janeiro et al. in 2015 found that a right-side kidney donation was linked to a higher occurrence of technical organ rejection due to a short renal vein and higher risk of narrowing and thrombosis of the renal veins. 20% of the Israeli sample analyzed here had their right-side kidney removed.

The donation process

The key question is whether the process takes adequate precautions given that the remaining kidney’s post-donation function could deteriorate? For instance, does the medical team explain to the donor that this could happen? The present study implies that the answer is ‘not always’. This is important in light of the fact that those donors interviewed for the present study who did receive a full explanation regarding the risks involved in donating a kidney were significantly less sure of their decision to donate (M=3.86) than those who were not explained the risks (M=4.72).

And what happens to those donors/patients who develop complications—23% in the present study? Are they adequately followed up by a doctor? The findings set out above raise substantial doubts with respect to these issues. Contrary to Ministry of Health expectations the follow-up is of very brief duration and mostly carried out by GPs, many of them not expert enough in nephrological matters. The present authors believe that all live kidney donors should be followed-up annually by a nephrologist.

The ethics: Given that developed nations are in effect indirectly funding many dubious live donation systems in the less developed world, the authors of the present study argue that an uncompromising insistence on allowing only purely altruistic (i.e. unpaid) live organ donations causes a moral wrong to weaker populations in the third world. One gets the feeling that the western world is burying its head in the sand when it comes to live donations, refusing to see what is actually happening in the field. The authors find this puritanical insistence on altruistic donation to be unreasonable, unrealistic, and unbalanced, and more than a little hypocritical. Lately a number of philosophers, rabbinic authorities, writers and doctors in the west have called for a re-examining the question of material remuneration for live organ donations, and have justified it in certain cases. This approach has been gaining momentum in the last few years [21].

All Israel’s three main religions and their component sects have declared official support for live organ donation. However, the current reality in Israel is that most Moslem Israeli-Arabs believe that Islam does not permit altruistic donations and so almost none of them will agree to do so. As for Israeli Jews, some rabbinic authorities prohibit live kidney donation, others allow it. Other halakhic issues are the prohibition against self-harm and whether man has full dominion over his own body. Again rabbinic opinion is divided [22,23]. It must be taken into account, however, that rabbinic opinion is of no concern to Israel’s large secular Jewish population.

Kidney donation from a live donor touches on the very value we put on life itself. On the one hand live donations save lives but, on the other, they entail physical harm to an otherwise healthy individual (the donor) without any medical advantage to himself/herself. As such, this goes against one of the core values of medical ethics—first do no harm. From this it follows that only when the donor derives significant emotional satisfaction from the fact that they are saving another’s life, is there any justification to cause them physical harm [24]. Is it moral and ethical to cause even small harm to a healthy human being at the very start of their life? Are we sure the donor is making a voluntary, rational decision about their body? Should the recipient of the kidney pay for it?

What motivates a healthy individual to donate an organ? When it comes to donating to a family member, the answer is intuitive: they are saving the life of a loved one, a family member. Yet we may also wonder what the true motivations of those who donate to a relative are. Is it the expectations of their family, the unvoiced pressure of their support system, that they give up one of their own body parts to save their relative’s life, suppressing any inner reluctance to do so?

But donating to a stranger, or even a friend, requires a deeper questioning of the donor’s motivations. Does he/she hope to secure a place in heaven, relying on the rabbinic and Koranic dictum that ‘he who saves a life, it is as though he saves the whole world’? Is it some sort of penance the donor thinks he/she owes? Or is it a financial transaction, affirming the capitalist assertion that anything can be bought for the right price?

Conclusion and Recommendation

Live donations raise moral, ethical and religious questions but these must be set against the urgent necessity to increase the rate of all donations, live and deceased. In discussing the shortcomings of the current live kidney donation process above we have set out several recommendations designed to make the process, including its long-term follow-up, more rigorous, more cautious and more strongly research-based. However, a recommendation of no less weight and importance is that Israel take vigorous and sustained action to multiply the number of deceased donations. Each deceased kidney donation means one less live donation, and thus a prevention of harm to a healthy individual. Not nearly enough is done in Israel to promote deceased donations and the result is that 50% of potential deceased donations are not realized. The main obstacle to this change of track from live to deceased donations is that the motivation to donate is undermined by Israelis’ option of buying a transplant overseas. In effect, the Israel Ministry of Health and the public healthcare system turn a blind eye to inadequately regulated organ donation overseas for the sake of saving the cost of dialysis in Israel. However, after undergoing a transplant abroad—an operation often performed without proper medical supervision—patients return to Israel to receive their follow-up treatment, adding to the local health-centers’ workload and detracting from the level of treatment local transplantees receive.

In light of the above the present authors’ recommendations are as follows:

• The small proportion of signatories to the National Transplant Centre deceased donor card must be increased by public education campaigns. These campaigns should involve all age groups from children to adults and all means of persuasion, from personal talks by organ donors and recipients to mass-donor card signings.

• The extent of many Israelis’ declared dependency on religious sanction for their agreement to donate an organ makes it clear that any public education initiative must be carried out in collaboration with religious leaders, local and central. We recommend setting up a council composed of representatives of medicine, nursing and all three major religions to take charge of this public educational initiative.

• A deceased’s signed donor-card must be made legally binding on their family, just as any will and testament is.

• Hospital nurses in general and in particular those working in nephrology and dialysis, need to be made more aware of the importance of deceased organ donation and also learn their religion’s position on all key transplantation issues since they are often the staffers who spend the most time alongside the family members of a potential donor [25].

• We also need to increase the number of trained transplant coordination nurses. It has been demonstrated that their work with the families of dying patients expands organ donation markedly.

• The present lead author’s long clinical experience shows that it is vital to train intensive care unit medical and nursing staff (in both adult and pediatric units) in the sensitive recruitment of organ donations, as they are most in contact with potential donors. It has been demonstrated that their work with the families of dying patients expands organ donation markedly.

• The government and Ministry of Health must institute financial remuneration for deceased donors’ families. This is done in countries such as Italy and Spain, who have invested heavily in this and managed to triple their donation pool.

• Establish (lawful) cooperation with neighbouring states to expand the pool of potential donors and recipients.

• Another way to increase deceased kidney donations is to add to the potential donors those who have died of heart failure (as well as brain deaths). This can augment the donor pool by 20% and is already the norm in the US, Spain, and one hospital in Israel [26].

• Consider national legislation instituting some form of presumed consent to donate (an opt-out system).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance in linguistic and structural editing of Mr. Nahum Steigman.

REFERENCES

- https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Organ_transplant/transplant/Pages/waiting_for_tra nsplants.aspx

- Steinberg A. What is it to do good medical ethics? An orthodox Jewish physician and ethicist’s perspective. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:125-8.

- https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Organ_transplant/transplant/Pages/default.aspx

- Ghods AJ. Living kidney donation: the outcomes for donors. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2010;1:63-71.

- Faber DA, Joshi S, Ciancio G. Demographic characteristics of non-directed altruistic kidney donors in the United States. J Kidney. 2016;2:2.

- https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Organ_transplant/transplant/Pages/default.aspx

- Gruenbaum BF, Jotkowitz A. The practical, moral, and ethical considerations of the new Israeli law for the allocation of donor organs. Transpl Proc. 2010;42:4475-8.

- Ministry of Health. Organ transplantation. 2017. Retrieved from:

- http://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Organ_transplant/transplant/Pages/default.aspx

- Levinsky NG. Organ donation by unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:430.

- Ratner LE. Laparascopic assisted live donor nephrectomy: a comparison with the open approach. Transplantation. 1997;63:229.

- Gibney EM, King AL, Maluf DG, et al. Living kidney donors requiring transplantation: focus on African mericans. Transplantation. 2007;84:647-9.

- Fehrman-Ekholm I, Norden G, Lennerling A, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease among live kidney donors. Transplantation. 2006;82:1646-8.

- Bay WH, Hebert LA. The living donor in kidney transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:719-27.

- Ellison MD, McBride MA, Taranto SE, et al. Living kidney donors in need of kidney transplants: a report from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Transplantation. 2002;74:1349-51.

- Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, et al. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:459-469.

- Faber DA, Joshi S, Ciancio G. Demographic characteristics of non-directed altruistic kidney donors in the United States. J Kidney. 2016;2:121.

- Messina E. Beyond the officially sacred, donor and believer: religion and organ transplantation. Transplantation Proc. 2015;47:2092-6.

- Justo-Janeiro JM, Orozco EP, Francisco J, et al. Transplantation of a horseshoe kidney from a living donor: Case report, long term outcome and donor. Int J Surg Cas Rep. 2015;15:21-5.

- Risaliti A, Sainz-Barriga M, Baccarani U, et al. Surgical complications after kidney transplantation. G Ital Nefrol. 2004;21 Suppl 26:S43-7.

- Steinberg A. Ethical issues in nephrology—Jewish perspectives. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 1996;11:961-3.

- Scott O, Jacobson E. Implementing presumed consent for organ donation in Israel: Public, religious and ethical issues. Israel Med Assoc J. 2007;9:777-81.

- Steinberg A. Organ donation: the duty to save life by charity. 2017.

- Smith CM. Origin and uses of Primum non nocere – Above all, do no harm. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:371-7.

- Muliira RS, Muliira JK. A review of potential Muslim organ donors' perspectives on solid organ donation: lessons for nurses in clinical practice. Nurs Forum. 2014;49:59-70.

- Akoh JA. Kidney donation after cardiac death. World J Nephrol. 2012;1:79-91.