Plasma-to-autopsy study of neurodegenerative diseases

Received: 19-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. PULJNCN-25-7514; Editor assigned: 21-Jan-2025, Pre QC No. PULJNCN-25-7514 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Feb-2025 QC No. PULJNCN-25-7514; Revised: 19-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. PULJNCN-25-7514 (R); Published: 26-Mar-2025

Citation: Yang SY, Liu HC. Plasma-to-autopsy study of neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2025;9(1):1-8.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objectives: Neuropathological evaluations are the gold standard for diagnosing a patient’s neurodegenerative disease and for validating biomarker tests. However, there may be a long delay between a biomarker determination and death. Plasma biomarker assays may provide a useful probabilistic determination of the identity of the causative condition and may easily be standardized across clinics. Unfortunately, validations of antemortem plasma biomarkers with postmortem neuropathology are rare. In this work, plasma was obtained from the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program (AZSAND/BBDP) a longitudinal clinicopathological study that collects plasma antemortem and conducts autopsies after death.

Methods: Plasma samples were collected from 1 to 1.5 years before death. Biomarkers, including Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, T-Tau, pTau181, α-synuclein, TDP-43, etc., in plasma were assayed using Immunomagnetic Reduction (IMR). Postmortem semi-quantitative histological assessments were done of the regional brain distributions of amyloid plaques, Neurofibrillary Tangles (NFT), Lewy-Type Synucleinopathy (LTS) and TDP proteinopathy.

Results: The levels of T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau can be used to estimate the histopathological brain loads of all of these. Plasma pTau181/TDP-43 predicts the regional and total brain NFT densities. Plasma α-synuclein levels positively correlate with LTS total brain load. Significantly higher levels of plasma TDP-43 were detected in subjects with histopathological TDP-43 pathology as compared to TDP-43-negative subjects.

Conclusion: These results demonstrate the significant relationships between antemortem plasma biomarkers and postmortem neuropathology.

Keywords

Neuropathology; Neurodegenerative disease; Plasma biomarkers; Immunomagnetic reduction

Introduction

Neuropathological evaluations are the gold standard for diagnosing a patient’s neurodegenerative disease. Anatomic vulnerabilities of amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, Pick bodies, Lewy bodies, and neural cytoplasmic and neural intranuclear inclusions are frequently found in various types of neurodegenerative diseases [1]. Pathological lesions are characterized by the accumulation of misfolded native peptides or proteins such as Amyloid β peptides (Aβ), tau proteins, α-synuclein and Transactive DNA-binding Protein 43 (TDP-43) [2-6]. In addition to proteinopathies, neuropathological diagnosis depends on the location (extracellular or intracellular), morphology and topography of the accumulated peptides/proteins and the cell types affected (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes) [7]. These pathological causes result in various clinical features of movement disorders, language disorders, and cognitive or behavioral disorders [8].

Antemortem anatomy for examining neuropathology is impossible in clinical practice. However, studies correlating anatomic investigations at autopsies with antemortem neuroimaging, such as amyloid Positron Emission Tomography (PET), tau PET, dopamine scanning, and metaiodobenzylguanidine scanning, have revealed the feasibility of in vitro examinations of neuropathology [9-12]. Although neuroimaging is approved for clinical use [13-16], it is not routinely performed because of its high cost and low availability. It would be better to have friendly evaluations for neuroimaging or neuropathology. Assays of relevant peptides/proteins in body fluids are promising for predicting neuropathology.

There has been considerable interest in using antemortem Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) biomarkers in autopsy-confirmed neurodegenerative diseases to discriminate Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) pathology from non-AD pathology [17-20]. The CSF biomarkers of interest are Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, total tau protein (T-Tau), phosphorylated tau protein at threonine 181 (pTau181), TDP-43, Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL), etc. The reported results show that CSF Aβ1-42 or pTau181 predominantly predict AD pathology [20]. The clinical sensitivity and specificity of identifying AD neuropathology increase when CSF pTau181 and Aβ1-42, TDP-43 and Aβ1-42, or Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 are combined [19]. CSF biomarkers have been listed in the diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. However, because of the perceived invasiveness of lumbar puncture, the clinical utility of CSF biomarkers is limited. Plasma biomarkers might be alternative fluid biomarkers for predicting neuropathology.

With the development of ultrasensitive assay technologies, precise quantitative detection of plasma biomarkers associated with neurodegenerative diseases has become feasible [22-25]. Many reports have revealed correlations between plasma biomarkers and clinical features, brain atrophy and the standardized uptake value ratio of Aβ tracers in the brain in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [26-32]. However, plasma-to-autopsy studies are rare in neurodegenerative diseases [33,34]. In this study, the ability of antemortem plasma biomarkers assayed with Immunomagnetic Reduction (IMR) to predict postmortem neuropathology, not limited to AD pathology, was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Subject enrollment

Human subjects were enrolled in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program (AZSAND/BBDP) a longitudinal clinicopathological study AZSAND/Brain and Body Donation Program (www.brainandbodydonationprogram.org) [35].

Neuropathological evaluation

All subjects received identical blinded neuropathological examinations [35] by a single observer, including summary regional brain density measures for total amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (for both is a summary score of 5 regional semi-quantitative 0-3 density scores for a maximum possible total of 15 in frontal, temporal and parietal lobes plus hippocampal CA1 and entorhinal/transentorhinal area), summary LTS regional brain density scores (summary score of semi-quantitative 0-4 density scores in 10 brain regions for a maximum possible total of 40), and staging using the unified staging system for Lewy body disorders [36], as well as substantia nigra depigmentation scores (0-3 for none, mild, moderate and severe) and assignment of CERAD neuritic plaque density, Braak neurofibrillary stage, and AD neuropathological change levels of low, intermediate or high, as described previously [37,38]. Pathological TDP-43 deposits were immunohistochemically detected and semi-quantitatively assessed (0-3 for none, sparse, moderate and severe), in sections of amygdala, hippocampal CA1, entorhinal/transentorhinal area, middle temporal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus, with antibodies to TDP-43 phosphorylated at phosphoserine residues 409-410 as previously described [39,40].

Plasma collection

We used EDTA tubes and processed blood within an hour of collection. Spin the blood tubes at 2,000x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma, buffy coat and red blood cells in Beckman Allegra X-14R. Collect plasma and centrifuge in Beckman Allegra X-14R for 5 minutes, 4°C at 3000x g to remove pellet cells. Aliquot and store plasma at -80°C. The antemortem plasma samples were collected from 1 to 1.5 years before death.

Plasma biomarkers assays

The plasma samples were sent to MagQu Co., Ltd., in Taiwan to assay Aβ1-42, T-Tau, total α-synuclein and TDP-43 using IMR. Frozen plasma samples were transferred to wet ice and then to room temperature. Fifteen minutes later, 60 μl of plasma was mixed with 60 μl of reagent for assaying Aβ1-42 (MF-AB2-0060, MagQu). For each of the other biomarkers, 40 μl of plasma was mixed with 80 μl of reagent (MF-TAU-0060, MF-ASC-0060, MF-TDP-0060, MagQu). An IMR analyzer (XacPro-S, MagQu) was used to measure the concentrations of biomarkers. For each batch of measurements, calibrators (CA-DEX-0060, CA-DEX-0080) and control solutions (CL-AB2-000T, CL-AB2-020T, CL-TAU-000T, CL-TAU-000T, CL-TAU-050T, CL-ASC-000T, CL-ASC-010T, CL-TDP-000T, CL-TDP-001T) were used. Measurements were repeated once for each biomarker per plasma sample. The average concentration of the duplicate measurements was reported.

Statistical methods

The discriminations of plasma biomarkers between neuropathological positives and negatives were analyzed via Student's t test. A p value lower than 0.05 denotes a significant difference in the levels of plasma biomarkers between neuropathologically positive and negative patients. Two-tailed Person’s correlation coefficients (r values) were analyzed between the biomarker levels and total counts of anatomic vulnerabilities. Analyses were performed via GraphPad Prism 5 and Med-Calc version 13.

Results

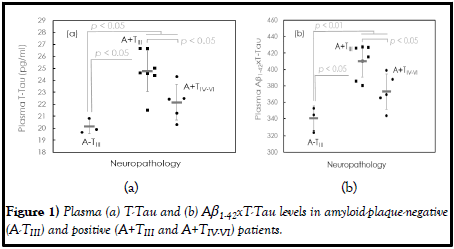

In this study, three autopsies were negative of amyloid plaques (A-), and twelve autopsies were positive of amyloid plaques (A+). The measured plasma individual and combined Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, T-Tau, pTau181, α-synuclein and TDP-43 concentrations are listed in Table 1. Among plasma biomarkers, TTau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau levels are significantly different between A- and A+ patients (T-Tau: p<0.05; Aβ1-42xT-Tau: p<0.01). There was no significant difference in the other biomarkers between A- and A+ patients (p>0.05). These findings suggest that both Aβ1-42 and tau contribute to the development of the observed amyloid plaques. The dot plots of the plasma T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau levels in A- and A+ are shown in Figure 1(a) and (b), respectively. A+ is associated with higher levels of plasma T-Tau and Aβ1-42xTTau than A-.

| Neuropathology | A- | A+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIII (n=3) | TIII (n=7) | TIV-VI (n=5) | Combined (n=12) | |

| Age of death (years) | 86.0 ± 3.0 | 81.0 ± 9.4 | 86.8 ± 3.6 | 83.3 ± 8.4 |

| Braak stage | III | III | IV-VI | III-VI |

| Biomarker | ||||

| Aβ1-40 (pg/ml) | 44.10 ± 5.74 | 46.67 ± 6.59 | 46.03 ± 4.07 | 46.40 ± 5.46 |

| Aβ1-42 (pg/ml) | 16.90 ± 0.42 | 16.60 ± 0.99 | 16.84 ± 0.51 | 16.70 ± 0.80 |

| T-Tau (pg/ml) | 20.14 ± 0.61 | 24.77 ± 1.73* | 22.16 ± 1.50*,+ | 23.69 ± 2.06* |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 3.93 ± 0.94 | 4.09 ± 0.56 | 3.88 ± 0.52 | 4.00 ± 0.53 |

| a-synuclein (fg/ml) | 95 ± 36 | 179 ± 117 | 96 ± 33 | 145 ± 99 |

| TDP-43 (pg/ml) | 0.246 ± 0.053 | 0.256 ± 0.036 | 0.188 ± 0.051 | 0.227 ± 0.054 |

| Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 | 0.387 ± 0.040 | 0.362 ± 0.056 | 0.368 ± 0.033 | 0.365 ± 0.046 |

| Aβ1-42xT-Tau | 340.4 ± 14.9 | 410.2 ± 19.7* | 373.0 ± 21.5*.+ | 394.7 ± 27.3* |

| Aβ1-42xpTau181 | 66.60 ± 17.33 | 67.82 ± 9.09 | 65.25 ± 7.15 | 66.75 ± 8.09 |

| Note: A-: Negative cases of amyloid plaques; A+: Positive cases of amyloid plaques TIII: Braak stage III; TIV-VI: Braak stage IV-VI *: p<0.05 compared with A-TIII; +: p<0.05 compared with A+TIII |

||||

Table 1: Measured antemortem plasma biomarkers in postmortem negative/positive cases of amyloid plaques.

The discrimination of A+ from A- is based on the Aβ plaque density over the regions of frontal cortex, temporal cortex, parietal cortex, hippocampus and entorhinal area. The correlations between plasma T-Tau and plaque density, plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau and plaque density in regions of frontal cortex, temporal cortex, parietal cortex, hippocampus and entorhinal area were analyzed via two-tailed Pearson’s correlation, as listed in Table 2. Plasma T-Tau levels do not correlate with any regional or combined Aβ plaque density. Plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau correlated significantly and positively with Aβ plaque density only in temporal cortex.

| Plasma biomarker Brain region |

T-Tau | Aβ1-42xT-Tau |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal cortex | 0.223 (p>0.05) | 0.231 (p>0.05) |

| Temporal cortex | 0.474 (p>0.05) | 0.522 (p<0.05) |

| Parietal cortex | 0.271 (p>0.05) | 0.276 (p>0.05) |

| Hippocampus | -0.066 (p>0.05) | -0.032 (p>0.05) |

| Entorhinal area | 0.480 (p>0.05) | 0.431 (p>0.05) |

| Combined | 0.306 (p>0.05) | 0.314 (p>0.05) |

Table 2: Pearson’s correlations between plasma T-Tau and Ab plaque density and between plasma Ab1-42xT-Tau and Ab plaque density in regions of frontal cortex, temporal cortex, parietal cortex, hippocampus and entorhinal area.

The Braak stage is a semiquantitative measure of the severity of the Neurofibrillary Tangle (NFT) pathology of the brain in AD patients. The Braak stages of the fifteen autopsies were examined, as listed. All three A-subjects were Braak stage III (TIII). Seven of the twelve A+ subjects were Braak stage III (TIII), and the other five A+ subjects were Braak stages IV, V or VI (TIV-VI). In A+, the levels of plasma T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau were relatively lower in TIV-VI than in TIII (p<0.05).

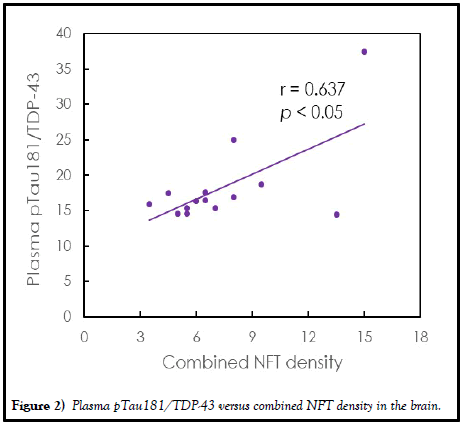

The relationships between individual and combined plasma biomarkers and NFT density in regions of frontal cortex, temporal cortex, parietal cortex, hippocampus and entorhinal area are investigated. There was no significant correlation between Aβ1-40, Aβ1-42, T-Tau, pTau181 or α-synuclein concentration and regional or combined NFT density (p>0.05). However, TDP-43 was significantly negatively correlated with NFT density at P (r=-0.540, p<0.05) and almost significantly correlated with combined NFT density (r=0.507, p=0.504), as listed in Table 3. By combining TDP-43 and pTau181, i.e., pTau181/TDP-43, significantly positive correlations with NFT density were found for the region of frontal cortex (r=0.641, p<0.05), temporal cortex (r=0.550, p<0.05), parietal cortex (r=0.724, p<0.01) and combined NFT density (r=0.637, p<0.05). The comparison of the plasma ptau181/TDP-43 and the combined NFT density is shown in Figure 2. The ptau181/TDP-43 promisingly predicts the NFT density in the brain.

| Plasma biomarker Brain region |

TDP-43 | pTau181/TDP-43 |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal cortex | -0.432 (p>0.05) | 0.641 (p<0.05) |

| Temporal cortex | -0.489 (p>0.05) | 0.550 (p<0.05) |

| Parietal cortex | -0.540 (p<0.05) | 0.724 (p<0.01) |

| Hippocampus | -0.104 (p>0.05) | 0.242 (p>0.05) |

| Entorhinal area | -0.392 (p>0.05) | 0.324 (p>0.05) |

| Combined | -0.507 (p>0.05; 0.504) | 0.637 (p<0.05) |

Table 3: Pearson’s correlations between plasma TDP-43 and NFT density and between plasma pTau181/TDP-43 and NFT density in regions of frontal cortex, temporal cortex, parietal cortex, hippocampus and entorhinal area.

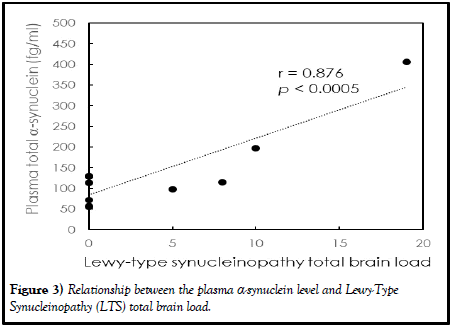

The two-tailed Pearson’s correlation coefficients between antemortem biomarker levels in plasma and the Lewy-Type Synucleinopathy (LTS) total brain load were analyzed, as listed in Table 4. The LTS total brain load is the sum of LTS in olfactory bulb, dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve (in medulla), locus ceruleus (in pons), substantia nigra, amygdala, transentorhinal area, cingulate gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule. Except for total α-synuclein, no significant correlation was found between measured plasma biomarkers and the LTS total brain load (p>0.05). The Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the measured total α-synuclein in plasma and the LTS total brain load was 0.876 (p<0.0005), as shown in Figure 3. The assayed total α-synuclein in plasma clearly and highly reflects the formation of Lewy bodies in the brain.

Figure 3) Relationship between the plasma α-synuclein level and Lewy-Type Synucleinopathy (LTS) total brain load.

| Biomarker | r (p value) |

|---|---|

| Aβ1-40 (pg/ml) | -0.058 (>0.05) |

| Aβ1-42 (pg/ml) | 0.160 (>0.05) |

| T-Tau (pg/ml) | 0.350 (0.05) |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 0.397 (>0.05) |

| a-synuclein (fg/ml) | 0.876 (<0.0005) |

| TDP-43 (pg/ml) | 0.298 (>0.05) |

| Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 | 0.095 (>0.05) |

| Aβ1-42xT-Tau | 0.483 (>0.05) |

| Aβ1-42xpTau181 | 0.411 (>0.05) |

Table 4: Correlations between antemortem plasma biomarkers and postmortem Lewy-Type Synucleinopathy (LTS) total brain load.

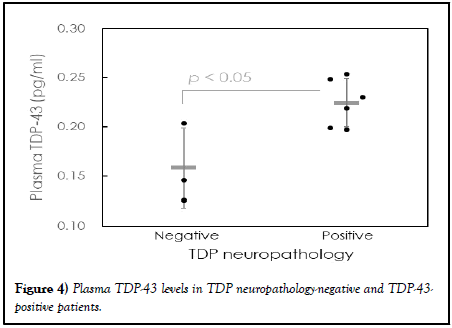

The observed plasma biomarker levels in subjects with negative and positive histopathological TDP-43 pathology are listed in Table 5. There were three subjects with negative TDP-43 pathology and six subjects with positive TDP-43 neuropathology. There was no significant difference in the levels of individual or combinations of Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein between negative and positive TDP-43 neuropathology (p>0.05). However, the TDP-43 levels in patients with positive TDP-43 neuropathology (0.225 ± 0.024 pg/ml) wre significantly greater than those in patients with negative TDP-43 neuropathology (0.158 ± 0.040 pg/ml, p<0.05), as shown in the dot plot in Figure 4. This implies that TDP-43 neuropathology in the brain is promisingly predicted with plasma TDP-43 assayed with IMR.

| TDP-43 Neuropathology |

Negative (n=3) | Positive (n=6) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of death (years) | 82.0 ± 2.6 | 85.0 ± 5.3 |

| Biomarker | ||

| Ab1-40 (pg/ml) | 45.45 ± 3.84 | 45.62 ± 5.91 |

| Ab1-42 (pg/ml) | 16.83 ± 0.54 | 16.57 ± 0.72 |

| T-Tau (pg/ml) | 21.92 ± 0.94 | 21.91 ± 3.14 |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 3.87 ± 0.75 | 3.59 ± 0.30 |

| a-synuclein (fg/ml) | 100 ± 91 | 92 ± 32 |

| TDP-43 (pg/ml) | 0.158 ± 0.040 | 0.225 ± 0.024* |

| Ab1-42/Ab1-40 | 0.372 ± 0.041 | 0.369 ± 0.054 |

| Ab1-42xT-Tau | 368.7 ± 17.8 | 362.9 ± 53.3 |

| Ab1-42xpTau181 | 64.85 ± 10.78 | 59.53 ± 6.38 |

| Note: *: p<0.05 | ||

Table 5: Measured antemortem plasma biomarkers in postmortem negative/positive TDP-43 neuropathology.

Discussion

As listed, both the plasma T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau levels discriminate A+ from A-. However, individual and combined Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 do not differentiate A+ from A-. This finding might suggest that the deposition of Aβ plaques in the brain is attributed to not only amyloid β peptides but also tau proteins. In fact, the contributions of amyloid β peptides and tau proteins to the formation of amyloid plaques in the brain are not independent. Several groups have reported interactions between amyloid β peptides and tau proteins, resulting in the accumulation of Aβ [41-45]. According to published papers, extracellular Aβ causes the phosphorylation of tau proteins with mediators of glycogen synthase kinase-3β or insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 [43,45]. The coexistence of Aβ and phosphorylated Tau (pTau) has been shown pathologically in AD animal models and human postmortem studies [41,42,44]. A significant correlation between Aβ1-42 and pTau, Aβ1-42 and T-Tau in AD patients was demonstrated in plasma studies [46]. In addition to accelerating phosphorylation, Aβ exacerbates the spread of tau proteins in the brain [47-50]. In mouse studies, amyloid deposition in the cortex leads to a dramatic increase in the speed of tau-protein propagation and an extraordinary increase in the spread of tau proteins to distal brain regions [47]. The acceleration of tau protein spreading in the human brain was validated by reports that abnormal levels of cortical tau proteins on PET are rarely found with normal levels of Aβ but are found outside the entorhinal cortex at abnormal levels of Aβ [49]. These results reveal that Aβ interacts with tau proteins. Thus, changes in Aβ levels could modify T-Tau levels. In this work, the T-Tau levels were found to be significantly and negatively correlated with the Aβ1-42 levels (r=-0.525, p<0.05). However, Aβ1-42 levels did not correlate with pTau181 levels (r=-0.182, p>0.05).

The ability to discriminate the occurrences of amyloid plaques shown in above figures could allow for distinguishing between Cognitive Unimpairment (CU), amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia (ADD) using plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau. This deduction is supported by many clinical studies, which revealed that the levels of plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau assayed with IMR continuously increase from the CU to aMCI to the ADD [28,51-53]. The cutoff value of plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau for differentiating aMCI patients from CU was suggested to be 403 (pg/ml)2, whereas it was 642 (pg/ml)2 for differentiating ADD patients from aMCI patients. The clinical sensitivity and specificity are greater than 0.8. Thus, plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau is not only an assessment parameter for aMCI and ADD but also an index for predicting disease severity. Hence, some groups have utilized changes in plasma Aβ1-42xT-Tau levels assayed with the IMR to monitor intervention effects in high-risk patients with AD or aMCI [54,55].

In addition, the discrimination of A+ from A-, plasma T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau differentiates advanced Braak stages (IV-VI) from early Braak stage (III) in A+. Notably, the levels of T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau were lower in A+TIV-VI than in A+TIII. Several reports have demonstrated significant elevations in plasma or CSF T-Tau or pTau levels as the Braak stage changes from zero to I or II [56-58]. However, the changes in plasma or CSF T-Tau or pTau as the Braak stage varies from III to VI are not consistent among studies. This could depend on the detected fragments, phosphorylation sites of the tau protein, coexistence of other biomarkers, atrophy of the brain, etc. In this work, the autopsies of TIII and TIV-VI in A+ patients were Aβ neuropathologically positive. This finding indicates the coexistence of Aβ with tau proteins in the included autopsies. The level of tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 181 (pTau181) was assayed. For the T-Tau assay, the antibody used in IMR is against the middle region of tau proteins, i.e., amino acids 209-229. The middle region is present in six isoforms of the tau protein. Only one antibody was used in the IMR system, without the secondary antibody. Once the epitope of amino acids 209-229 is exposed, whether in the form of full-length proteins, fragments or oligomers, etc., the tau protein is assayed. More investigations are needed to clarify the relationships between T-Tau or pTau and tau neuropathology in the brain.

As shown in Table 3, TDP-43 levels were negatively correlated with regional NFT density in parietal cortex. Meanwhile, pTau181/TDP-43 significantly and positively correlated with regional and combined NFT densities in the brain. This finding might suggest that TDP-43 could suppress the expression of pTau181 or T-Tau to prevent the formation of NFT in the brain. Gu, et al. proposed a possible mechanism for the suppression of T-Tau or pTau expression [59,60]. TDP-43 promoted tau mRNA instability by binding to two (UG)n elements in the 3’-Untranslated Region (3’-UTR) of tau mRNA. Thus, tau protein expression was suppressed. The downregulation of T-Tau and pTau with TDP-43 could potentially contribute to the negative correlation between TDP-43 and regional NFT density in parietal cortex and the positive correlation between pTau181/TDP-43 and regional/combined NFT densities. However, further studies are needed.

The results in Figure 3 reveal the feasibility of predicting Lewy bodies in the brain using plasma α-synuclein. Lewy bodies are the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Thus, plasma α-synuclein can potentially be used to assess PD. Several groups have demonstrated the feasibility of differentiating PD patients from normal controls by assaying plasma α-synuclein with the IMR [61-64]. High clinical sensitivity and specificity were found.

In addition to the LTS total brain load, the regional LTS load in the olfactory bulb, dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve (in medulla), locus ceruleus (in pons), amygdala, substantia nigra, transentorhinal area, cingulate gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule and limbic lobe were analyzed in this work [35,36,65]. Among the observed regional LTS load, plasma α-synuclein levels were most strongly correlated with regional LTS load in the limbic lobe (r=0.958, p<0.0001). This finding implies that plasma α-synuclein levels significantly predict vulnerability in the limbic lobe in PD patients. This deduction is consistent with the observations of Chen, et al. [65], who reported a weak association between plasma α-synuclein levels and thinning of the limbic cortex.

Beach, et al. correlated LTS load with clinical features such as cognitive impairment and motor disorders in PD patients [36]. Higher LTS total brain load result in lower MMSE scores and higher UPDRS III scores. LTD total brain load predicts disease severity in PD patients. With the positive correlation between plasma α-synuclein levels and the LTS total brain load shown in Figure 3, the plasma α-synuclein density promisingly predicts disease severity in PD patients. Lin, et al. demonstrated the prediction of cognitive decline in PD patients via plasma α-synuclein levels assayed with the IMR [61].

TDP-43 pathology is the hallmark of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia (BVFTD). As shown in Figure 4, significantly increased levels of plasma TDP-43 were found in patients with positive TDP-43 neuropathology. Hence, TDP-43 in the fluid body is suggested as a potential diagnostic biomarker for ALS and BVFTD. Reported increases in CSF TDP-43 in patients with ALS [67]. Steinacker, et al. reported increases in CSF TDP-43 levels in both ALS and FTD patients [68]. Furthermore, Zecca, et al. proposed that high levels of CSF TDP-43 may be associated with rapid disease progression and reduced survival [69]. In addition to CSF, Chatterjee, et al. reported an increase in TDP-43 in plasma extracellular vesicles in patients with ALF or FTD [70]. Yang, et al. utilized IMR to assay soluble TDP-43 in plasma and found a clear difference in plasma TDP-43 levels between FTD patients and normal controls [71]. However, not all published results are consistent. Reported a decrease in serum TDP-43 levels in FTD patients with C9orf72 repeat expansion or a concomitant motoneuron disease phenotype [72]. This finding implies that genotypes and comorbidities could manipulate changes in body-fluid TDP-43 in individuals with ALS or FTD.

TDP-43 pathology is found not only in ALS and FTD patients but also in AD patients. According to pathology studies, 20% to 50% of AD patients have TDP-43 pathology [73,74]. Yang, et al. reported that 20.6% of AD patients have increased levels of plasma TDP-43 [71]. This plasma study result coincides with that of TDP-43 pathology studies. Josephs, et al. reported that the most frequent deposition of TDP-43 was in the limbic system (67%) [75]. TDP-43 pathology in limbic regions leads to limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE), which is associated with anamnestic dementia syndrome, which is a clinical feature of AD. Hence, to assess AD in elderly individuals, not only plasma AD and tau but also plasma TDP-43 should be assayed.

Conclusion

The plasma-to-autopsy relationships were explored in this work. The antemortem biomarkers in plasma were assayed by using immunomagnetic reduction. The levels of T-Tau and Aβ1-42xT-Tau discriminate amyloid-plaque positives from negatives at autopsy and differentiate advanced from early Braak stages in positive cases of amyloid plaques. Plasma pTau181/TDP-43 predicts the regional NFT density in parietal cortex and the combined NFT density in the brain. Plasma α-synuclein levels positively correlate with Lewytype synucleinopathy total brain load. Significantly higher levels of plasma TDP-43 were detected in subjects with histopathological TDP-43 pathology as compared to TDP-43-negative subjects.

Limitations

Owing to the limited sources of autopsies at the brain bank, few subjects were included in this work. In addition, the time interval between blood draw and autopsy is 1-1.5 years. This might explain the slight inconsistency between antemortem plasma biomarkers and postmortem neuropathology.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Lih-Fen Lue for the help on designing the study. We are also grateful to the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders/Brain and Body Donation Program at Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, Arizona for the provision of human biological materials. The Brain and Body Donation Program has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG019610 and P30AG072980, Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Antemortem blood plasma collection was funded in part by Grant No. CTR040636 from the Arizona Department of Health Services as well as by Gates Ventures.

Conflict of Interests

Shieh-Yueh Yang and Huei-Chun Liu are employees of MagQu Co., Ltd., Shieh-Yueh Yang is a shareholder of MagQu Co., Ltd.

References

- Dugger BN, Dickson DW. Pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;9(7):a028035.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, et al. Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839-40.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hardy J, Duff K, Hardy KG, et al. Genetic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Amyloid and its relationship to tau. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(5):355-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, et al. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33(1):95-130.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuo YM, Kokjohn TA, Beach TG, et al. Comparative analysis of amyloid chemical structure and amyloid plaque morphology of transgenic mouse and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(16):12991-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130-3.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cullinane PW, Wrigley S, Parmera JB, et al. Pathology of neurodegenerative disease for the general neurologist. Pract Neurol. 2024;24(3):188-99.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robinson JL, Xie SX, Baer DR, et al. Pathological combinations in neurodegenerative disease are heterogeneous and disease-associated. Brain. 2023:146(6);2557-69.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas AJ, Attems J, Colloby SJ, et al. Autopsy validation of 123I-FP-CIT dopaminergic neuroimaging for the diagnosis of DLB. Neurology. 2017;88(3):276-83.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lowe VJ, Lundt ES, Albertson SM, et al. Neuroimaging correlates with neuropathologic schemes in neurodegenerative disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(7):927-39.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsubara T, Kameyama M, Tanaka N, et al. Autopsy validation of the diagnostic accuracy of 123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy for Lewy Body disease. Neurology. 2022;98(16):e1648-59.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kotari V, Southekal S, Navitsky M, et al. Early tau detection in fortaucipir images: Validation in autopsy-confirmed data and implications for disease progression. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15(1):41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshita M, Taki J, Yamada M. A clinical role for [123I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in the distinction between dementia of the Alzheimer's-type and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(5):583-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kung HF, Kung MP, Wey SP. Clinical acceptance of a molecular imaging agent: A long march with [99mTc]TRODAT. Nuclear Med Biol. 2007;34(7):787-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vandenberghe R, Adamczuk K, Dupont P, et al. Amyloid PET in clinical practice: Its place in the multidimensional space of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;2:497-511.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith R, Hägerström D, Pawlik D, et al. Clinical utility of tau positron emission tomography in the diagnostic workup of patients with cognitive symptoms. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(7):749-56.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruzova M, Rusina R, Stejskalova Z, et al. Autopsy-diagnosed neurodegenerative dementia cases support the use of cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers in the diagnostic work-up. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10837-1-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grothe MJ, Moscoso A, Ashton NJ, Ket al. Associations of fully automated CSF and novel plasma biomarkers with Alzheimer disease neuropathology at autopsy. Neurology. 2021;97(12):e1229-42.

- Mattsson-Carlgren N, Grinberg LT, Boxer A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2022;98(11):e1138-1-14.

- Wang ZB, Tan L, Gao PY, et al. Associations of the A/T/N profiles in PET, CSF, and plasma biomarkers with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology at autopsy. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(10):4421-35.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jack Jr CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2018;14(4):535-62.

- Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(6):595-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang SY, Chiu MJ, Chen TF, et al. Detection of plasma biomarkers using immunomagnetic reduction: A promising method. Neurol Ther. 2017;6(Suppl 1):S37-56.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakamura A, Kaneko N, Villemagne VL, et al. High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;554(7691):249-54.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamashita K, Watanabe S, Ishiki K, et al. Fully automated chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassays showing high correlation with immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry assays for β-amyloid (1-40) and (1-42) in plasma samples. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2021;576:22-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gerards M, Schild AK, Meiberth D, et al. Alzheimer's disease plasma biomarkers distinguish clinical diagnostic groups in memory clinic patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2022;51(2):182-92.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Therriault J, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, et al. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using plasma biomarkers adjusted to clinical probability. Nat Aging. 2024;41529-37.

- Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Hu CJ, et al. Nanoparticle-based immunomagnetic assay of plasma biomarkers for differentiating dementia and prodromal states of Alzheimer's disease-A cross-validation study. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2020;26:102182.

- Chiu MJ, Chen YF, Chen TF, et al. Plasma tau as a window to the brain-Negative associations with brain volume and memory function in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:3132-42.

- Thambisetty M, Simmons A, Hye A, et al. Plasma biomarkers of brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. PloS One. 2011;6(4):e28527.

- Tzen KY, Yang SY, Chen TF, et al. Plasma A but not tau is related to brain PiB retention in early Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(9):830-6.

- Jack Jr CR, Wiste HJ, Algeciras-Schimnich A, et al. Predicting amyloid PET and tau PET stages with plasma biomarkers. Brain. 2023;146(5):2029-44.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montoliu-Gaya L, Alosco ML, Yhang E, et al. Optimal blood tau species for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology: An immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry and autopsy study. Acta Neuropathol. 2024;147(5):5.

- Kac PR, González-Ortiz F, Emeršic A, et al. Plasma p-tau212 antemortem diagnostic performance and prediction of autopsy verification of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Nature Commun. 2024;15:2615.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, et al. Arizona study of aging and neurodegenerative disorders and brain and body donation program. Neuropathol. 2015;35(1):354-89.

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Lue L, et al. Arizona Parkinson's disease consortium. Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: Correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(5):613-34.

- The National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):S1-2.

- Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-Alzheimer's association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1-1.

- Hasegawa M, Arai T, Nonaka T, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1):60-70.

- Arnold SJ, Dugger BN, Beach TG. TDP-43 deposition in prospectively followed, cognitively normal elderly individuals: Correlation with argyrophilic grains but not other concomitant pathologies. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:51-7.

- Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293(5534):1487-91.

- Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, et al. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301L tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293(5534):1491-5.

- Cho JH, Johnson GV. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates tau at both primed and unprimed sites: Differential impact on microtubule binding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):187-93.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pennanen L, Gotz J. Different tau epitopes define Abeta42-mediated tau insolubility. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337(4):1097-101.

- Watanabe K, Uemura K, Asada M, et al. The participation of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 released by astrocytes in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Brain. 2015;8:82.

- Chiu MJ, Yang SY, Chen TF, et al. Synergistic association between plasma Aβ1-42 and p-tau in Alzheimer’s disease but Not in Parkinson’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12(8):1376-83.

- Pooler AM, Polydoro M, Maury EA, et al. Amyloid accelerates tau propagation and toxicity in a model of early Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:14.

- d’Errico P, Meyer-Luehmann M. Mechanisms of pathogenic tau and Aβ protein spreading in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:265.

- Doré V, Krishnadas N, Bourgeat P, et al. Relationship between amyloid and tau levels and its impact on tau spreading. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2225-32.

- Binette AP, Franzmeier N, Spotorno N, et al. Amyloid-associated increases in soluble tau relate to tau aggregation rates and cognitive decline in early Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6635.

- Chiu MJ, Yang SY, Horng HE, et al. Combined plasma biomarkers for diagnosing mild cognition impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(12):1530.

- Jiao F, Yi F, Wang Y, et al. The validation of multifactor model of plasma Aβ42 and total-tau in combination with MoCA for diagnosing probable Alzheimer disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:212.

- Lue LF, Sabbagh MN, Chiu MJ, et al. Plasma levels of A42 and tau identified probable Alzheimer’s dementia: Findings in two cohorts. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:226.

- Lin LJ, Li KY. Comparing the effects of olfactory-based sensory stimulation and board game training on cognition, emotion, and blood biomarkers among individuals with dementia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1003325.

- Liu WT, Huang HT, Hung HY, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure reduces plasma neurochemical levels in patients with OSA: A pilot study. Life. 2023;13(3):613.

- Chen SD, Lu JY, Li HQ, et al. Staging tau pathology with tau PET in Alzheimer’s disease: A longitudinal study. Transl Psychia. 2021;11(1):483.

- Montoliu-Gaya L, Benedet AL, Tissot C, et al. Mass spectrometric simultaneous quantification of tau species in plasma shows differential associations with amyloid and tau pathologies. Nat Aging. 2023;3(4):661.

- Feizpour A, Doecke JD, Doré V, et al. Detection and staging of Alzheimer’s disease by plasma pTau217 on a high throughput immunoassay platform. EBioMed. 2024;109:105405.

- Gu J, Wu F, Xu W, et al. TDP-43 suppresses tau expression via promoting its mRNA instability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(10):6177-93.

- Yang M, Qi R, Liu Y, et al. Casein kinase 1δ phosphorylates TDP-43 and suppresses its function in tau mRNA processing. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;91(4):1527-39.

- Lin CH, Yang SY, Horng HE, et al. Plasma α-synuclein predicts cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(10):818-24.

- Chang CW, Yang SY, Yang CC, et al. Plasma and serum alpha-synuclein as a biomarker of diagnosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1388.

- Chen NC, Chen HL, Li SH, et al. Plasma levels of α-synuclein, Aβ-40 and T-tau as biomarkers to predict cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:112.

- Malaty GR, Decourt B, Shill HA, et al. Biomarker assessment in Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies by the immunomagnetic reduction assay and clinical measures. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2024;8(1):1361-71.

- Adler CH, Beach TG, Zhang N, et al. Unified staging system for Lewy Body disorders: Clinicopathologic correlations and comparison to Braak staging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78(10):891-9.

- Chen CH, Lee BC, Lin CH. Integrated plasma and neuroimaging biomarkers associated with motor and cognition severity in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(1):77-88.

- Noto Y, Shibuya K, Sato Y, et al. Elevated CSF TDP-43 levels in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Specificity, sensitivity, and a possible prognostic value. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(2):140-3.

- Steinacker P, Hendrich C, Sperfeld AD, et al. TDP-43 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1481-87.

- Zecca C, Dell’Abate MT, Capozzo R, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid TDP-43 is a possible predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2020;94(15):4143.

- Chatterjee M, Ozdemir S, Fritz C, et al. Plasma extracellular vesicle tau and TDP-43 as diagnostic biomarkers in FTD and ALS. Nat Med. 2024;30(6):1771-83.

- Yang SY, Liu HC, Lin CY, et al. Development of assaying plasma TDP-43 utilizing immunomagnetic reduction. J Neurol Disord. 2020;8.

- Katisko K, Huber N, Kokkola T, et al. Serum total TDP-43 levels are decreased in frontotemporal dementia patients with C9orf72 repeat expansion or concomitant motoneuron disease phenotype. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):151.

- Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, et al. Staging TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:441-50.

- Uryu K, Nakashima-Yasuda H, Forman MS, et al. Concomitant TAR-DNA-binding protein 43 pathology is present in Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration but not in other tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(6):555-64.

- Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, et al. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer's disease impact clinical features. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(5):697-709.