The meaning of quality of life and relationships for women living with interstitial cystitis

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Lorna Butler

Room 122 Forrest Building Dalhousie University, School of Nursing, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3J5

Tel: 902-494-3499

Fax: 902-494-3487

E-mail: lorna.butler@dal.ca

Keywords

Meaning; Relationships; Sexual health

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a disease of the bladder that occurs more often in women. There is no standard test for IC and the frustration of diagnosing by exclusion is frequently experienced by both patients and health professionals [1]. This process frequently creates a sense of helplessness and loss of control for patients when symptoms go unmanaged, after multiple interventions, and as family members struggle to understand the disruption to their lives and relationships [2]. The purpose of this study is to describe women’s ‘lived’ experience with IC; specifically, its meaning and the psychosocial impact on women and their families.

Little is known about the life experience of individuals diagnosed with IC. The existing literature relates predominately to acute exacerbations and associated treatments. IC, found primarily in women over 40 years of age, is accompanied by unexplained and sometimes debilitating symptoms for extended periods of time before a diagnosis is confirmed [3]. The etiology and pathogenesis of IC are unknown, rendering individuals vulnerable to ongoing treatment of multiple symptoms until a diagnosis can be determined. The most common symptoms include urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, pelvic pain, bladder spasms, dyspareunia and hematuria [4]. IC also appears to have an association with other chronic conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and sensitive skin [5].

Approximately 75% of patients with IC experience pain in the lower abdomen and women, in particular, experience vaginal pain that is either constant or occurs daily [5]. The presence of bladder ulcers reportedly increases the intensity of the pain, causing spasms and a hot, stabbing sensation. IC pain appears to be aggravated by stress, constrictive clothing and sexual intercourse [5-7]. Certain foods may produce IC pain, particularly acidic and carbonated beverages, alcohol, coffee and spicy food. IC pain may be relieved by urination and medical treatment.

Living with IC impacts quality of life. A sense of worthlessness in family responsibilities and relationships has been described. Difficulty in performing tasks and maintaining employment status have also been reported [2]. Patients have indicated that the inability to diagnose IC can lead to confusion, compounding the distress that is already experienced. When the etiology of an illness is unknown, the ability to predict, prevent or manage its effects are often compromised [8]. The patient’s ability to cope with the experiences of IC has received little attention in the literature. Given the chronicity of IC, the severity of symptoms and the limited sustained effectiveness of treatment, the overall impact on psychosocial distress and impaired functioning is essentially unknown [7-10].

The documentation of symptoms leading to a diagnosis of IC and the frequency with which these events are experienced have been well described. Intervention strategies to manage self-care have recently begun to emerge [1,7]; however, most studies have not explored the meaning of symptoms experienced or the impact of IC and its effects on quality of life. How IC relates to daily events and how well the individual incorporates the stress of IC into daily living is unknown. This search for meaning of an illness is a personal experience that is neither easily understood nor well described [11].

Methods

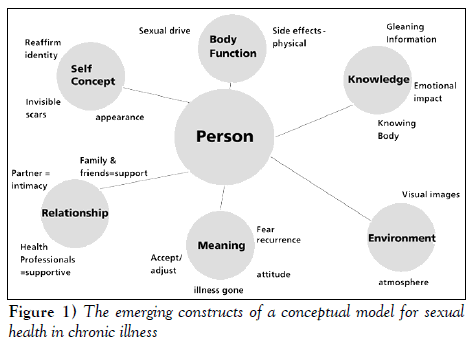

This qualitative study used a semistructured interview guide based on a conceptual framework of sexual health [12] (Figure 1). The study consisted of face to face interviews with the women. Data were analyzed using manifest content analysis methodology to describe and quantify the phenomena of the women’s experience with IC [13,14].

Study population

The sample consisted of 20 women treated for exacerbation or ‘flare-ups’ of IC, and the study demographics are shown in Table 1. Ages ranged from 25 to 70 years, and most were married (n=12, 60%). The majority of women had a high school diploma. Eight women were fully employed. Fifty per cent of the subjects were within a low to moderate income bracket. All of the women were heterosexual and 18 reported being sexually active before their diagnosis. After the diagnosis of IC, the proportion of those women who were sexually active decreased. Only one woman reported using lubricating gel while all the other women indicated that no devices or medications were used to aid sexual activity. Most of the women reported that they had other chronic illnesses in addition to IC and the most common comorbidities were bowel disorders (n=5; 45%), asthma (n=4; 20%), fibromyalgia (n=3; 15%) and arthritis (n=3; 15%).

| Demographic data | (n) | Patient (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 45 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 12 | 60 |

| Significant other | 2 | 10 |

| Common-law | 3 | 15 |

| Average number of years with spouse or partner | 14 | |

| Average number of children | 2 | |

| Education | ||

| University degree | 4 | 20 |

| Partial university | 2 | 10 |

| Vocational education | 8 | 40 |

| High school | 3 | 15 |

| Other | 2 | 10 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 8 | 40 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 30 |

| Retired | 1 | 5 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 4 | 20 |

| $21,000 to $25,000 | 1 | 5 |

| $26,000 to $40,000 | 4 | 20 |

| $41,000 to $65,000 | 6 | 30 |

| Greater than $65,000 | 2 | 10 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 20 | 100 |

| Sexually active before intersitial cystitis | 18 | 90 |

| Currently sexually active | 11 | 55 |

Table 1: Demographic data for women (n=20)

Instrumentation

Demographic data were collected using a form designed specifically for this study. Interviews were semistructured using a set of predetermined questions as a guide. To verify the accuracy and relevance of the questions included in the semistructured interview guide, the IC support group within the local region reviewed the questions. Changes were incorporated based on their recommendations. The semistructured interview guide was also based on the conceptualization of the sexual health model and relevant literature on IC. The model provided questions about the experience of living with IC, the impact on relationships with partners, family and friends, and the impact IC has had on self-identity and sexual well being. The model included sources of support and information for learning about and managing IC. The interviews also addressed how the diagnosis of IC was made and the length of time to receive a diagnosis.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Research and Review Committee of the study hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all sub- jects. Individuals conducting interviews were skilled in interpersonal relationship-building and communicating with patients and families. Participant confidentiality was ensured by coding demographic and transcribed interview data. Participants were given the option of having their audio tapes returned at the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic data. Interview data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by manifest content analysis. Manifest content analysis uses a systematic approach to reduce the content of communicated information, in the form of text or recordings, by identifying patterns and clusters of words or statements that have similar meanings. The categorical scheme in this study was deductive using the sexual health model as a guide [14]. This approach provided a method of categorizing unstructured qualitative data [13]. Data were examined to identify particular themes as the unit of analysis. Within each theme, theoretical categories were developed. Using a predetermined set of rules, data were assigned to each category [14]. To test for the emergence of mutually exclusive categories, two investigators examined and categorized the data. A 95% agreement for inter-rater reliability was achieved.

Results

The findings in this study are presented by explanatory variables that emerged as the data were categorized (Table 2). The variables were consistent with the sexual health model. No new constructs were identified as contributing to the model in this patient population, although some variations did exist between the subcategory themes. The order in which the categories are represented reflects their importance to the participants. The most predominant category to emerge from the data was relationships. This was followed by the category of knowledge. Body function, meaning of IC and sexual self-concept were similar in thematic representation, although to a slightly lesser degree. The category of environment was seldom referenced.

| Subcategory title | (n) | (f) |

|---|---|---|

| Relationships | 101 | 259 |

| Knowledge of one’s health and IC | 82 | 204 |

| Meaning of illness | 69 | 217 |

| Body function | 53 | 212 |

| Sexual self-concept | 48 | 135 |

| Environment | 8 | 9 |

| Other | 20 | 47 |

Table 2: Distribution and frequency of the women’s responses for each category of the sexual health model

Relationships

The themes categorized under ‘relationship’ referred to experiences of the women in establishing and maintaining relationships with health care professionals, family and friends. The main theme to be identified was the relationship between the women and their physicians, including the urologist and the family physician (n=20). This influence did not seem to be generalized to all health professionals, because the relationship with nurses was mentioned specifically although to a much lesser degree (n=5). Women generally spoke of relationships with physicians as positive but had experiences which they referred to as poor bedside manner, impersonal, cold and uncompassionate. The women believed that physicians were unwilling to volunteer more than minimal information. Family physicians tended to be regarded more negatively. One urologist consistently seemed to be quite highly regarded and praised by the women he cared for. Nurses were referenced by patients as easier to talk to, eager to volunteer information and willing to extend their support. Consistent with the urologist relationship, patients who made reference to nurses tended to mention one particular nurse with whom they felt truly comfortable, respected and cared for.

When commenting on the relationship with their partner, many women (n=15) said their partners were quite understanding and supportive. Some talked about the impact of their suffering and pain on their partner. Some suggested this could be why their partner was more understanding of IC than friends and relatives. As a result, some women said they discussed IC only with their partners and they had a higher level of communication in their relationship because of this sharing. Not all relationships dealt with IC in this manner. Some women reported that there was very little discussion of IC in their relationship. Almost all women reported that they did not spend as much time with their partner doing social activities because of the IC.

While many women spoke of their relationship with their partner, few referred to intimacy in their relationship (n=8). Of these women, all said that intercourse occurred on a less frequent basis. Many said they communicated a great deal with their partners about their inability to engage in sexual activity and expressed intimacy in other ways.

Some comments were made about the strain IC has had on relationships with partners and family. Only one woman spoke of strain in her relationship with her partner due to IC. She felt that her husband divorced her due to the lack of sexual intercourse and intimacy in their relationship. Other women referred more to the strain of living with IC on children and relatives. One women explained her daughter’s inability to stay all night at friends’ sleepovers because of concern about her mother’s health while she was away. Another identified strain as the inability to participate in family activities such as spending a family day at the beach. Few references were made to partners as caregivers (n=4). Women spoke of feeling guilty that their partner and children were doing so much around the house but they appreciated the help. One woman expressed concern for parents. “They are at retirement age now but instead of spending time with each other they spend it mostly at our house,” she said.

Women attending support groups referred to the group as having a very positive influence on their lives (n=15). The women expressed their happiness and sense of relief to discuss IC with other women and family members experiencing the same challenges in life. With regard to family, many women felt their partners and children were very understanding and supportive (n=14).

Knowledge of one’s health and IC

The variable, knowledge, referred to how individuals became informed about IC, in addition to their experiential knowledge. Almost all women found their sources of information to be useful (n=18 ). Women processed knowledge in meaningful ways that supported their abilities not only to make informed decisions (n=9) but also to manage the illness experience (n=13). Numerous strategies were employed to manage the illness and improve activities of daily living. These included timing events relative to symptom occurence and urinary frequency and considering treatment interventions such as surgery and implantation of devices to control symptoms. The women seemed to be well informed about their treatment options yet some (n=11) felt they were required to seek out the needed information.

Becoming informed (n=16) was achieved by both professional and experiential knowledge. The following quote suggests the tension associated with obtaining information from physicians: “He answered the questions very lightly and I asked for more details; he told me it would be too technical and I told him that I would understand it, would he please supply me with the medical research of that reason.” The emotional impact of new knowledge was at times frightening. Women (n=15) expressed difficulties with coping, denial, comparison of the diagnosis with cancer and acknowledged the lack of treatment success. For some women, it took time to comprehend the material.

Meaning of illness

This variable referred to the women’s comments regarding what it means to live with IC and how this relates to their sense of sexual well being. The most prominent theme to emerge was the acceptance and adjustment to living with IC (n=19). The biggest adjustment was reported to be living life close to washrooms and learning to deal with the symptoms in daily life. Fear of flare-ups, importance of bathrooms, attitude and hope were the themes frequently expressed.

Many women (n=16) held attitudes about their IC treatments and physicians. Women commonly took the attitude that they were dealt IC in their life and they would just have to learn to cope with it. Many were discouraged and frustrated with the treatment they received from health professionals and believed that to feel better they would have to take a more active, aggressive role in managing how they were being treated.

Many women (n=16) spoke about their frequent trips to the bathroom. One woman stated “if you go somewhere you have to know where the bathroom is because you go so often and it actually makes me feel like I don’t have much of a life”. Another commented “if you are at a meal or go to a show you have to get up and go to the bathroom. You have to plan more around things, you just can’t go and do things”.

Some women spoke about how fear of IC influenced their life (n=11). Women talked about the fear of a flare-up and fear of the future in terms of their prognosis. Many spoke of how they engaged in substantially fewer social outings because of the fear that symptoms will occur and be unmanageable in public. Others spoke of a fear of the future and a continual decline in quality of life.

Few women expressed feelings of hope (n=7). Of those that did, many referred to what one woman termed, ‘fake hope’. They spoke of how seeing the physician was associated with a sense of hope for a new treatment, despite knowing nothing more could be offered. Many also spoke of fake hope in terms of the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatments. Few women expressed feelings of hope for a cure or a better life in the future.

Body function

Two main themes emerged from this category. The first was the influence that side effects had on the lives of women with IC. All women in the sample (n=20) reported side effects to be a major concern. Common complaints consisted of pain, urgency, frequency of urination, extreme fatigue, irritable bowel, skin rashes, diarrhea, joint pain and gastric ulcers from medications. The second common theme to emerge concerned sexual functioning. Many reported painful intercourse and fear that intercourse would exacerbate vaginal infections.

For those women who continued to work, the workplace was a source of concern for many. They were concerned about high absenteeism due to sickness and finding time to frequently go to the washroom while at work. Many also talked about the emotional pain experienced from the lack of understanding and sympathy, in some cases from both employers and coworkers. As one women expressed, “I lost a job on account of it…I had a flare-up and I wasn’t there to answer the phone when it was ringing or do what I was supposed to be doing because I was running to the bathroom all the time”.

Sexual self-concept

The main theme that emerged under this variable was the influence IC has had on the women’s gender identities (n=15). How they viewed themselves as a woman seemed to be disrupted by difficulties and pain with sexual intercourse. Female identity also seemed to be greatly affected by the odour associated with DMSO treatments. Many reported feeling selfconscious, dirty and being made to feel isolated by partners, family members, friends and coworkers. Some said it made them feel like less of a woman because it greatly impacted their sense of femininity.

Some women made reference to a disruption in their identities as mothers. This was provoked by a general decline in the ability to do household chores, no longer being the predominant caregiver for children and relying on a partner, parents and children to do tasks considered part of the role of a mother. Stress and sadness were also reported due to missing out on previously enjoyed activities, such as attending children’s school events, sports games, camping or trips often because of the inaccessibility of washrooms or fear of causing disruptions to the proceedings because of the extended time required for the family to accommodate IC-related needs to participate.

Some women made reference to their identity as a partner (n=9). Concerns were the impact that the decrease in activities of daily living would have on their relationship, as well as the stigma of being a ‘sick wife’. Others believed their identity as a partner was positively supported by their husband. This support seemed to be related to the women believing that if they eased the burden relating to their inability to participate in family events, others were not impacted by the IC: “I tell him, ‘you go honey, there is no need for you to stay home and why should you suffer’, so he goes and he loves to go”.

Environment

Women who referred to atmosphere (n=7) spoke of the hospital becoming like a second home due to the frequency of visits. Two women referred to how the urology clinic seemed to be designed for men given the emphasis on prostate cancer, as evi-denced by the abundance of literature and reference material scattered around the clinic. One woman made reference to visual imagery in terms of the odour of her DMSO treatments reminding her of the smell of death.

Other

Several patients (n=14) reported their frustrations with eating and the restrictions of the IC diet. Some women found the conflicting diets for IC and other conditions such as bladder infection, irritable bowel syndrome and diabetes a major source of stress. Foods some women were instructed to eat to improve one condition would cause a flare-up of another condition, causing frustration and anxiety. Relatively few women (n=6) reported financial strain to be influential on their quality of life while living with IC. Concern was generally due to refusal of insurance companies to pay for specific medications or procedures.

Discussion

Limitations

The present study was conducted within one province equipped with one major referral centre for the treatment of IC at a urology clinic with a consistent staff of physicians and nurses. To what extent the results would have remained the same given a diverse setting and variations in approaches to diagnosis and treatment is unknown. The ability to generalize the findings is limited to the participants and the accrual setting. The ability to make recommendations about cultural sensitivity is also limited by the homogeneity of the study sample.

Summary and Conclusions

The dominant perspective within the existing quality of life literature on IC and in other chronic conditions depicts sexual well being as a physical entity. Therefore, an individual is either sexually functional or dysfunctional after an illness event. A critical analysis of the existing literature showed that empirical research supported the function/dysfunction measurement of sexuality. The thoughts of patients describing their lived experiences and how IC impacts their lives as sexual beings are absent from the literature. The conceptual underpinnings of this study reject the notion of dysfunction. To apply a dysfunction measurement would negate the substantive contributions participants have made in challenging the views of their sexual well being.

The purpose of the present study was to describe women’s life experiences with IC; specifically, its meaning and the psychosocial impact on quality of life and relationships.

The findings of the present study demonstrated that a gap exists in clinical practice relative to sexual health as a component of IC care delivery. Health professionals may be unaware of how women with IC perceive the exchange of information about their illness and treatment and the effect this interaction may have on their ability to establish meaningful relationships with others. There is a pressing need to develop educational programs for health professionals on sexual well being and to ensure that, while educated, the staff working within an IC clinic are also comfortable to include a sexual health component in the provision of care [15].

It has been suggested that attention should be given to the perspectives of both the patients and their family members to understand the real meaning of life when a chronic illness is experienced within the context of family relationships [16]. The women in the study were quite knowledgeable about how their illness was to be treated, but they were less well informed about what IC really was and why a cure was not available. This knowledge was often challenged by an inability to convince others, including health professionals, family and friends of the authenticity of their illness. The search for knowledge as a way to understand and manage the illness experience was frequently left to the woman, who was then responsible to educate her partner and family. Information has an impact on how one may act in terms of sense of self, such as change in mood [17]. Further, how an individual processes, retains and compartmentalizes relevant information may be important in the attempt to recreate their lives and relationships given the uncertainty of their illness experiences.

While the six concepts of the sexual health model were maintained, differences were noted in the subcategories (Table 3). The women with IC who participated, on average, were younger than most other women previously studied. This may account for the thematic finding of ability to work as a component of body function. Second, the urgency to find bathroom facilities and the significance of defining one’s activities by washroom locations had a huge impact on the meaning IC has to one’s life and relationships. To what extent these themes are representative to others with IC or to different chronic illness samples will require future testing.

| Variable | Subtheme | Patient responses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (f) | ||

| Relationship | Physicians | 20 | 66 |

| Partners | 15 | 42 | |

| Support groups | 15 | 39 | |

| Family | 14 | 41 | |

| Friends | 14 | 28 | |

| Nurses | 5 | 9 | |

| Intimacy in relationship | 8 | 18 | |

| Caregiver strain | 4 | 5 | |

| Strain on relationship | 6 | 11 | |

| Knowledge of one’s | Sources of information | 18 | 41 |

| health and IC | Becoming informed | 16 | 48 |

| Emotional impact of new knowledge | 15 | 41 | |

| Managing the illness | 13 | 38 | |

| Acquiring needed information | 11 | 21 | |

| Making choices | 9 | 15 | |

| Meaning of illness | Fear of flare-up | 11 | 24 |

| Attitude | 16 | 57 | |

| Accept or adjust | 19 | 73 | |

| Meaning of bathroom | 16 | 47 | |

| Hope | 7 | 16 | |

| Body function | Side effects | 20 | 127 |

| Exercise | 5 | 7 | |

| Ability to work | 11 | 27 | |

| Sexual functioning | 17 | 51 | |

| Sexual self concept | Appearance (internal) | 8 | 21 |

| Appearance (external) | 8 | 19 | |

| Identity as female | 15 | 59 | |

| Identity as mother | 7 | 14 | |

| Identity as partner | 9 | 21 | |

| Invisible scars | 1 | 1 | |

| Environment | Atmosphere | 7 | 8 |

| Visual image | 1 | 1 | |

F Frequency; IC Interstitial cystitis

Table 3: Distribution and frequency of responses by variables and subthemes

The present study included only women diagnosed with IC. It is recognized that different capacities exist for men and women and, thus, the different organs involved in illnesses. For example, women with IC or breast cancer will have different experiences from men with prostate cancer or end stage renal disease. These diverse systems nevertheless affect one’s capacity as a sexual being, regardless of sex, and thus the following six concepts of the model have emerged: relationships, meaning, sexual self concept, body function, knowledge and environment. What continues to be unknown is the influence of the determinants of health on sexual well being. Demographically, this study did not provide any evidence to support relevance of the six concepts in diverse populations. Further study in this area is essential given the changing characteristics of the Canadian population.

The findings of this study did support the conceptual basis of sexual health as a broad, multidimensional concept. While sexual functioning was a contributing variable, this aspect of the women’s life was not representative of their overall sexual well being. The traditional use of sexual function as a proxy measure of overall sexual well being would not be relevant for this group of women. Scientifically, it is important to continue to test this model and advance the theoretical base for determining sexual health. Development of an instrument that can be used to quantitatively measure sexual health variables is critical. This instrument could then be incorporated in large samples such as clinical trials that presently are limited by tools that focus only on sexual dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Queen Elizabeth II (QEII) Health Sciences Nursing Research Fund and the Department of Urology. We thank both departments for their interest in this research project. The work originated at the urology clinic of the QEII Health Sciences Centre. The members of the research team would like to thank Donna McInnis for the many hours of work provided for transcription of audiotaped interviews. Laura Evans is also thanked for contributions and interest in the sexual well being of women with interstitial cystitis. Chris Pauley provided statistical support for qualitative, unstructured data analysis, and we thank him for the time invested in our project. The staff within the urology clinic at the QEII provided outstanding support for participant accrual and we could not have conducted the study without their help. To the women who participated in this study, we are deeply grateful for the time and interest extended to us and the patience and understanding in helping us learn more about the impact of IC within their lives.

References

- Peters K. The diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 2000;20:101-7.

- Bates P, Getz B, Gibbs E, Neu L, Pobursky J. Clinical conversations: Nurses who work with patients with interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 2000;20:109-8.

- Mobley D, Baum N. Interstitial cystitis: When urgency and frequency mean more than routine inflammation. Postgrad Med 1996;99:201-8.

- Koziol J, Clark D, Gittes R, Tan E. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: A survey of 374 patients. J Urol 1993;149:465-9.

- Alagiri M, Chottinger S, Ratner V, Slade D, Hanno P. Interstitial cystitis: Unexplained associations with other chronic disease and pain syndromes. Urol 1997;49(Suppl 5A):52-7.

- Webster D. Recontextualizing sexuality in chronic illness: Women and interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1997;18:575-89.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Self-care effectiveness and health outcomes in women with interstitial cystitis: Implications for mental health clinicians. Issues in Mental Health Nurs 1998;19:495-519.

- Draucker C. Coping with a difficult-to-diagnose illness: The examples of interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1991;12:191-8.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Use and effectiveness of psychological self-care strategies for interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1995;16:463-75.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Use and effectiveness of sexual self-care strategies for interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 1995;15:14-22.

- Taylor S. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. Am Psychol 1983;38:1161-71.

- Butler L, Banfield V, Svenison T, Allen K. Conceptualizing sexual health in cancer care. West J Nurs Res 1998;20:683-705.

- McLaughlin F, Marascuila L. Advanced nursing and health care research: Quantification approaches. London: WB Saunders, 1990.

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: Method applications and issues Health Care Women Int 1992;13:313-21.

- Butler L, Banfield V. Oncology nurses views on the provision of sexual health in cancer care. J Sex Reprod Med 2001;1:35-44.

- Thorne S, Patterson J. Shifting image of chronic illness. Image: J Nurs Scholar 1998;30:173-7.

- Showers C, Abramson L, Hogan M. The dynamic self: How the content and structure of the self-concept change with mood. J Person Soc Psych 1998;75:478-93.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Lorna Butler

Room 122 Forrest Building Dalhousie University, School of Nursing, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3J5

Tel: 902-494-3499

Fax: 902-494-3487

E-mail: lorna.butler@dal.ca

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To describe women’s ‘lived’ experience of interstitial cystitis (IC); specifically, its meaning and the psychosocial impact on quality of life for women using the conceptual model of sexual health.

DESIGN: Qualitative study using purposive sampling. The study consisted of semistructured interviews with women diagnosed with IC. Data were analyzed using manifest content analysis methodology.

SETTING: Interviews were conducted either in the home or at the time of the woman’s clinic visit.

POPULATION STUDIED: Participants were required to have been treated with pentosan polysulfate, intravesical therapy of dimethyl sulfoxide or a combination of both. Women who had undergone bladder dilation only and those in remission were excluded.

MAIN RESULTS: Findings supported the sexual health model with relationships emerging as the most predominant category impacting the lives of women with IC.

CONCLUSIONS: Specific to communicating issues of sexual health, the findings of the present study further supported the existing gaps in clinical practice for care delivery. There is a need to educate health professionals about the impact of IC on sexual well being and to ensure that the staff working within an IC clinic are comfortable with including sexual health in the provision of care.

Keywords

Meaning; Relationships; Sexual health

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a disease of the bladder that occurs more often in women. There is no standard test for IC and the frustration of diagnosing by exclusion is frequently experienced by both patients and health professionals [1]. This process frequently creates a sense of helplessness and loss of control for patients when symptoms go unmanaged, after multiple interventions, and as family members struggle to understand the disruption to their lives and relationships [2]. The purpose of this study is to describe women’s ‘lived’ experience with IC; specifically, its meaning and the psychosocial impact on women and their families.

Little is known about the life experience of individuals diagnosed with IC. The existing literature relates predominately to acute exacerbations and associated treatments. IC, found primarily in women over 40 years of age, is accompanied by unexplained and sometimes debilitating symptoms for extended periods of time before a diagnosis is confirmed [3]. The etiology and pathogenesis of IC are unknown, rendering individuals vulnerable to ongoing treatment of multiple symptoms until a diagnosis can be determined. The most common symptoms include urinary frequency and urgency, nocturia, pelvic pain, bladder spasms, dyspareunia and hematuria [4]. IC also appears to have an association with other chronic conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and sensitive skin [5].

Approximately 75% of patients with IC experience pain in the lower abdomen and women, in particular, experience vaginal pain that is either constant or occurs daily [5]. The presence of bladder ulcers reportedly increases the intensity of the pain, causing spasms and a hot, stabbing sensation. IC pain appears to be aggravated by stress, constrictive clothing and sexual intercourse [5-7]. Certain foods may produce IC pain, particularly acidic and carbonated beverages, alcohol, coffee and spicy food. IC pain may be relieved by urination and medical treatment.

Living with IC impacts quality of life. A sense of worthlessness in family responsibilities and relationships has been described. Difficulty in performing tasks and maintaining employment status have also been reported [2]. Patients have indicated that the inability to diagnose IC can lead to confusion, compounding the distress that is already experienced. When the etiology of an illness is unknown, the ability to predict, prevent or manage its effects are often compromised [8]. The patient’s ability to cope with the experiences of IC has received little attention in the literature. Given the chronicity of IC, the severity of symptoms and the limited sustained effectiveness of treatment, the overall impact on psychosocial distress and impaired functioning is essentially unknown [7-10].

The documentation of symptoms leading to a diagnosis of IC and the frequency with which these events are experienced have been well described. Intervention strategies to manage self-care have recently begun to emerge [1,7]; however, most studies have not explored the meaning of symptoms experienced or the impact of IC and its effects on quality of life. How IC relates to daily events and how well the individual incorporates the stress of IC into daily living is unknown. This search for meaning of an illness is a personal experience that is neither easily understood nor well described [11].

Methods

This qualitative study used a semistructured interview guide based on a conceptual framework of sexual health [12] (Figure 1). The study consisted of face to face interviews with the women. Data were analyzed using manifest content analysis methodology to describe and quantify the phenomena of the women’s experience with IC [13,14].

Study population

Figure 1: The emerging constructs of a conceptual model for sexual health in chronic illness

The sample consisted of 20 women treated for exacerbation or ‘flare-ups’ of IC, and the study demographics are shown in Table 1. Ages ranged from 25 to 70 years, and most were married (n=12, 60%). The majority of women had a high school diploma. Eight women were fully employed. Fifty per cent of the subjects were within a low to moderate income bracket. All of the women were heterosexual and 18 reported being sexually active before their diagnosis. After the diagnosis of IC, the proportion of those women who were sexually active decreased. Only one woman reported using lubricating gel while all the other women indicated that no devices or medications were used to aid sexual activity. Most of the women reported that they had other chronic illnesses in addition to IC and the most common comorbidities were bowel disorders (n=5; 45%), asthma (n=4; 20%), fibromyalgia (n=3; 15%) and arthritis (n=3; 15%).

| Demographic data | (n) | Patient (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 45 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 12 | 60 |

| Significant other | 2 | 10 |

| Common-law | 3 | 15 |

| Average number of years with spouse or partner | 14 | |

| Average number of children | 2 | |

| Education | ||

| University degree | 4 | 20 |

| Partial university | 2 | 10 |

| Vocational education | 8 | 40 |

| High school | 3 | 15 |

| Other | 2 | 10 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 8 | 40 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 30 |

| Retired | 1 | 5 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 4 | 20 |

| $21,000 to $25,000 | 1 | 5 |

| $26,000 to $40,000 | 4 | 20 |

| $41,000 to $65,000 | 6 | 30 |

| Greater than $65,000 | 2 | 10 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 20 | 100 |

| Sexually active before intersitial cystitis | 18 | 90 |

| Currently sexually active | 11 | 55 |

Table 1: Demographic data for women (n=20)

Instrumentation

Demographic data were collected using a form designed specifically for this study. Interviews were semistructured using a set of predetermined questions as a guide. To verify the accuracy and relevance of the questions included in the semistructured interview guide, the IC support group within the local region reviewed the questions. Changes were incorporated based on their recommendations. The semistructured interview guide was also based on the conceptualization of the sexual health model and relevant literature on IC. The model provided questions about the experience of living with IC, the impact on relationships with partners, family and friends, and the impact IC has had on self-identity and sexual well being. The model included sources of support and information for learning about and managing IC. The interviews also addressed how the diagnosis of IC was made and the length of time to receive a diagnosis.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Research and Review Committee of the study hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all sub- jects. Individuals conducting interviews were skilled in interpersonal relationship-building and communicating with patients and families. Participant confidentiality was ensured by coding demographic and transcribed interview data. Participants were given the option of having their audio tapes returned at the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic data. Interview data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by manifest content analysis. Manifest content analysis uses a systematic approach to reduce the content of communicated information, in the form of text or recordings, by identifying patterns and clusters of words or statements that have similar meanings. The categorical scheme in this study was deductive using the sexual health model as a guide [14]. This approach provided a method of categorizing unstructured qualitative data [13]. Data were examined to identify particular themes as the unit of analysis. Within each theme, theoretical categories were developed. Using a predetermined set of rules, data were assigned to each category [14]. To test for the emergence of mutually exclusive categories, two investigators examined and categorized the data. A 95% agreement for inter-rater reliability was achieved.

Results

The findings in this study are presented by explanatory variables that emerged as the data were categorized (Table 2). The variables were consistent with the sexual health model. No new constructs were identified as contributing to the model in this patient population, although some variations did exist between the subcategory themes. The order in which the categories are represented reflects their importance to the participants. The most predominant category to emerge from the data was relationships. This was followed by the category of knowledge. Body function, meaning of IC and sexual self-concept were similar in thematic representation, although to a slightly lesser degree. The category of environment was seldom referenced.

| Subcategory title | (n) | (f) |

|---|---|---|

| Relationships | 101 | 259 |

| Knowledge of one’s health and IC | 82 | 204 |

| Meaning of illness | 69 | 217 |

| Body function | 53 | 212 |

| Sexual self-concept | 48 | 135 |

| Environment | 8 | 9 |

| Other | 20 | 47 |

Table 2: Distribution and frequency of the women’s responses for each category of the sexual health model

Relationships

The themes categorized under ‘relationship’ referred to experiences of the women in establishing and maintaining relationships with health care professionals, family and friends. The main theme to be identified was the relationship between the women and their physicians, including the urologist and the family physician (n=20). This influence did not seem to be generalized to all health professionals, because the relationship with nurses was mentioned specifically although to a much lesser degree (n=5). Women generally spoke of relationships with physicians as positive but had experiences which they referred to as poor bedside manner, impersonal, cold and uncompassionate. The women believed that physicians were unwilling to volunteer more than minimal information. Family physicians tended to be regarded more negatively. One urologist consistently seemed to be quite highly regarded and praised by the women he cared for. Nurses were referenced by patients as easier to talk to, eager to volunteer information and willing to extend their support. Consistent with the urologist relationship, patients who made reference to nurses tended to mention one particular nurse with whom they felt truly comfortable, respected and cared for.

When commenting on the relationship with their partner, many women (n=15) said their partners were quite understanding and supportive. Some talked about the impact of their suffering and pain on their partner. Some suggested this could be why their partner was more understanding of IC than friends and relatives. As a result, some women said they discussed IC only with their partners and they had a higher level of communication in their relationship because of this sharing. Not all relationships dealt with IC in this manner. Some women reported that there was very little discussion of IC in their relationship. Almost all women reported that they did not spend as much time with their partner doing social activities because of the IC.

While many women spoke of their relationship with their partner, few referred to intimacy in their relationship (n=8). Of these women, all said that intercourse occurred on a less frequent basis. Many said they communicated a great deal with their partners about their inability to engage in sexual activity and expressed intimacy in other ways.

Some comments were made about the strain IC has had on relationships with partners and family. Only one woman spoke of strain in her relationship with her partner due to IC. She felt that her husband divorced her due to the lack of sexual intercourse and intimacy in their relationship. Other women referred more to the strain of living with IC on children and relatives. One women explained her daughter’s inability to stay all night at friends’ sleepovers because of concern about her mother’s health while she was away. Another identified strain as the inability to participate in family activities such as spending a family day at the beach. Few references were made to partners as caregivers (n=4). Women spoke of feeling guilty that their partner and children were doing so much around the house but they appreciated the help. One woman expressed concern for parents. “They are at retirement age now but instead of spending time with each other they spend it mostly at our house,” she said.

Women attending support groups referred to the group as having a very positive influence on their lives (n=15). The women expressed their happiness and sense of relief to discuss IC with other women and family members experiencing the same challenges in life. With regard to family, many women felt their partners and children were very understanding and supportive (n=14).

Knowledge of one’s health and IC

The variable, knowledge, referred to how individuals became informed about IC, in addition to their experiential knowledge. Almost all women found their sources of information to be useful (n=18 ). Women processed knowledge in meaningful ways that supported their abilities not only to make informed decisions (n=9) but also to manage the illness experience (n=13). Numerous strategies were employed to manage the illness and improve activities of daily living. These included timing events relative to symptom occurence and urinary frequency and considering treatment interventions such as surgery and implantation of devices to control symptoms. The women seemed to be well informed about their treatment options yet some (n=11) felt they were required to seek out the needed information.

Becoming informed (n=16) was achieved by both professional and experiential knowledge. The following quote suggests the tension associated with obtaining information from physicians: “He answered the questions very lightly and I asked for more details; he told me it would be too technical and I told him that I would understand it, would he please supply me with the medical research of that reason.” The emotional impact of new knowledge was at times frightening. Women (n=15) expressed difficulties with coping, denial, comparison of the diagnosis with cancer and acknowledged the lack of treatment success. For some women, it took time to comprehend the material.

Meaning of illness

This variable referred to the women’s comments regarding what it means to live with IC and how this relates to their sense of sexual well being. The most prominent theme to emerge was the acceptance and adjustment to living with IC (n=19). The biggest adjustment was reported to be living life close to washrooms and learning to deal with the symptoms in daily life. Fear of flare-ups, importance of bathrooms, attitude and hope were the themes frequently expressed.

Many women (n=16) held attitudes about their IC treatments and physicians. Women commonly took the attitude that they were dealt IC in their life and they would just have to learn to cope with it. Many were discouraged and frustrated with the treatment they received from health professionals and believed that to feel better they would have to take a more active, aggressive role in managing how they were being treated.

Many women (n=16) spoke about their frequent trips to the bathroom. One woman stated “if you go somewhere you have to know where the bathroom is because you go so often and it actually makes me feel like I don’t have much of a life”. Another commented “if you are at a meal or go to a show you have to get up and go to the bathroom. You have to plan more around things, you just can’t go and do things”.

Some women spoke about how fear of IC influenced their life (n=11). Women talked about the fear of a flare-up and fear of the future in terms of their prognosis. Many spoke of how they engaged in substantially fewer social outings because of the fear that symptoms will occur and be unmanageable in public. Others spoke of a fear of the future and a continual decline in quality of life.

Few women expressed feelings of hope (n=7). Of those that did, many referred to what one woman termed, ‘fake hope’. They spoke of how seeing the physician was associated with a sense of hope for a new treatment, despite knowing nothing more could be offered. Many also spoke of fake hope in terms of the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatments. Few women expressed feelings of hope for a cure or a better life in the future.

Body function

Two main themes emerged from this category. The first was the influence that side effects had on the lives of women with IC. All women in the sample (n=20) reported side effects to be a major concern. Common complaints consisted of pain, urgency, frequency of urination, extreme fatigue, irritable bowel, skin rashes, diarrhea, joint pain and gastric ulcers from medications. The second common theme to emerge concerned sexual functioning. Many reported painful intercourse and fear that intercourse would exacerbate vaginal infections.

For those women who continued to work, the workplace was a source of concern for many. They were concerned about high absenteeism due to sickness and finding time to frequently go to the washroom while at work. Many also talked about the emotional pain experienced from the lack of understanding and sympathy, in some cases from both employers and coworkers. As one women expressed, “I lost a job on account of it…I had a flare-up and I wasn’t there to answer the phone when it was ringing or do what I was supposed to be doing because I was running to the bathroom all the time”.

Sexual self-concept

The main theme that emerged under this variable was the influence IC has had on the women’s gender identities (n=15). How they viewed themselves as a woman seemed to be disrupted by difficulties and pain with sexual intercourse. Female identity also seemed to be greatly affected by the odour associated with DMSO treatments. Many reported feeling selfconscious, dirty and being made to feel isolated by partners, family members, friends and coworkers. Some said it made them feel like less of a woman because it greatly impacted their sense of femininity.

Some women made reference to a disruption in their identities as mothers. This was provoked by a general decline in the ability to do household chores, no longer being the predominant caregiver for children and relying on a partner, parents and children to do tasks considered part of the role of a mother. Stress and sadness were also reported due to missing out on previously enjoyed activities, such as attending children’s school events, sports games, camping or trips often because of the inaccessibility of washrooms or fear of causing disruptions to the proceedings because of the extended time required for the family to accommodate IC-related needs to participate.

Some women made reference to their identity as a partner (n=9). Concerns were the impact that the decrease in activities of daily living would have on their relationship, as well as the stigma of being a ‘sick wife’. Others believed their identity as a partner was positively supported by their husband. This support seemed to be related to the women believing that if they eased the burden relating to their inability to participate in family events, others were not impacted by the IC: “I tell him, ‘you go honey, there is no need for you to stay home and why should you suffer’, so he goes and he loves to go”.

Environment

Women who referred to atmosphere (n=7) spoke of the hospital becoming like a second home due to the frequency of visits. Two women referred to how the urology clinic seemed to be designed for men given the emphasis on prostate cancer, as evi-denced by the abundance of literature and reference material scattered around the clinic. One woman made reference to visual imagery in terms of the odour of her DMSO treatments reminding her of the smell of death.

Other

Several patients (n=14) reported their frustrations with eating and the restrictions of the IC diet. Some women found the conflicting diets for IC and other conditions such as bladder infection, irritable bowel syndrome and diabetes a major source of stress. Foods some women were instructed to eat to improve one condition would cause a flare-up of another condition, causing frustration and anxiety. Relatively few women (n=6) reported financial strain to be influential on their quality of life while living with IC. Concern was generally due to refusal of insurance companies to pay for specific medications or procedures.

Discussion

Limitations

The present study was conducted within one province equipped with one major referral centre for the treatment of IC at a urology clinic with a consistent staff of physicians and nurses. To what extent the results would have remained the same given a diverse setting and variations in approaches to diagnosis and treatment is unknown. The ability to generalize the findings is limited to the participants and the accrual setting. The ability to make recommendations about cultural sensitivity is also limited by the homogeneity of the study sample.

Summary and Conclusions

The dominant perspective within the existing quality of life literature on IC and in other chronic conditions depicts sexual well being as a physical entity. Therefore, an individual is either sexually functional or dysfunctional after an illness event. A critical analysis of the existing literature showed that empirical research supported the function/dysfunction measurement of sexuality. The thoughts of patients describing their lived experiences and how IC impacts their lives as sexual beings are absent from the literature. The conceptual underpinnings of this study reject the notion of dysfunction. To apply a dysfunction measurement would negate the substantive contributions participants have made in challenging the views of their sexual well being.

The purpose of the present study was to describe women’s life experiences with IC; specifically, its meaning and the psychosocial impact on quality of life and relationships.

The findings of the present study demonstrated that a gap exists in clinical practice relative to sexual health as a component of IC care delivery. Health professionals may be unaware of how women with IC perceive the exchange of information about their illness and treatment and the effect this interaction may have on their ability to establish meaningful relationships with others. There is a pressing need to develop educational programs for health professionals on sexual well being and to ensure that, while educated, the staff working within an IC clinic are also comfortable to include a sexual health component in the provision of care [15].

It has been suggested that attention should be given to the perspectives of both the patients and their family members to understand the real meaning of life when a chronic illness is experienced within the context of family relationships [16]. The women in the study were quite knowledgeable about how their illness was to be treated, but they were less well informed about what IC really was and why a cure was not available. This knowledge was often challenged by an inability to convince others, including health professionals, family and friends of the authenticity of their illness. The search for knowledge as a way to understand and manage the illness experience was frequently left to the woman, who was then responsible to educate her partner and family. Information has an impact on how one may act in terms of sense of self, such as change in mood [17]. Further, how an individual processes, retains and compartmentalizes relevant information may be important in the attempt to recreate their lives and relationships given the uncertainty of their illness experiences.

While the six concepts of the sexual health model were maintained, differences were noted in the subcategories (Table 3). The women with IC who participated, on average, were younger than most other women previously studied. This may account for the thematic finding of ability to work as a component of body function. Second, the urgency to find bathroom facilities and the significance of defining one’s activities by washroom locations had a huge impact on the meaning IC has to one’s life and relationships. To what extent these themes are representative to others with IC or to different chronic illness samples will require future testing.

| Variable | Subtheme | Patient responses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (f) | ||

| Relationship | Physicians | 20 | 66 |

| Partners | 15 | 42 | |

| Support groups | 15 | 39 | |

| Family | 14 | 41 | |

| Friends | 14 | 28 | |

| Nurses | 5 | 9 | |

| Intimacy in relationship | 8 | 18 | |

| Caregiver strain | 4 | 5 | |

| Strain on relationship | 6 | 11 | |

| Knowledge of one’s | Sources of information | 18 | 41 |

| health and IC | Becoming informed | 16 | 48 |

| Emotional impact of new knowledge | 15 | 41 | |

| Managing the illness | 13 | 38 | |

| Acquiring needed information | 11 | 21 | |

| Making choices | 9 | 15 | |

| Meaning of illness | Fear of flare-up | 11 | 24 |

| Attitude | 16 | 57 | |

| Accept or adjust | 19 | 73 | |

| Meaning of bathroom | 16 | 47 | |

| Hope | 7 | 16 | |

| Body function | Side effects | 20 | 127 |

| Exercise | 5 | 7 | |

| Ability to work | 11 | 27 | |

| Sexual functioning | 17 | 51 | |

| Sexual self concept | Appearance (internal) | 8 | 21 |

| Appearance (external) | 8 | 19 | |

| Identity as female | 15 | 59 | |

| Identity as mother | 7 | 14 | |

| Identity as partner | 9 | 21 | |

| Invisible scars | 1 | 1 | |

| Environment | Atmosphere | 7 | 8 |

| Visual image | 1 | 1 | |

F Frequency; IC Interstitial cystitis

Table 3: Distribution and frequency of responses by variables and subthemes

The present study included only women diagnosed with IC. It is recognized that different capacities exist for men and women and, thus, the different organs involved in illnesses. For example, women with IC or breast cancer will have different experiences from men with prostate cancer or end stage renal disease. These diverse systems nevertheless affect one’s capacity as a sexual being, regardless of sex, and thus the following six concepts of the model have emerged: relationships, meaning, sexual self concept, body function, knowledge and environment. What continues to be unknown is the influence of the determinants of health on sexual well being. Demographically, this study did not provide any evidence to support relevance of the six concepts in diverse populations. Further study in this area is essential given the changing characteristics of the Canadian population.

The findings of this study did support the conceptual basis of sexual health as a broad, multidimensional concept. While sexual functioning was a contributing variable, this aspect of the women’s life was not representative of their overall sexual well being. The traditional use of sexual function as a proxy measure of overall sexual well being would not be relevant for this group of women. Scientifically, it is important to continue to test this model and advance the theoretical base for determining sexual health. Development of an instrument that can be used to quantitatively measure sexual health variables is critical. This instrument could then be incorporated in large samples such as clinical trials that presently are limited by tools that focus only on sexual dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Queen Elizabeth II (QEII) Health Sciences Nursing Research Fund and the Department of Urology. We thank both departments for their interest in this research project. The work originated at the urology clinic of the QEII Health Sciences Centre. The members of the research team would like to thank Donna McInnis for the many hours of work provided for transcription of audiotaped interviews. Laura Evans is also thanked for contributions and interest in the sexual well being of women with interstitial cystitis. Chris Pauley provided statistical support for qualitative, unstructured data analysis, and we thank him for the time invested in our project. The staff within the urology clinic at the QEII provided outstanding support for participant accrual and we could not have conducted the study without their help. To the women who participated in this study, we are deeply grateful for the time and interest extended to us and the patience and understanding in helping us learn more about the impact of IC within their lives.

References

- Peters K. The diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 2000;20:101-7.

- Bates P, Getz B, Gibbs E, Neu L, Pobursky J. Clinical conversations: Nurses who work with patients with interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 2000;20:109-8.

- Mobley D, Baum N. Interstitial cystitis: When urgency and frequency mean more than routine inflammation. Postgrad Med 1996;99:201-8.

- Koziol J, Clark D, Gittes R, Tan E. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: A survey of 374 patients. J Urol 1993;149:465-9.

- Alagiri M, Chottinger S, Ratner V, Slade D, Hanno P. Interstitial cystitis: Unexplained associations with other chronic disease and pain syndromes. Urol 1997;49(Suppl 5A):52-7.

- Webster D. Recontextualizing sexuality in chronic illness: Women and interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1997;18:575-89.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Self-care effectiveness and health outcomes in women with interstitial cystitis: Implications for mental health clinicians. Issues in Mental Health Nurs 1998;19:495-519.

- Draucker C. Coping with a difficult-to-diagnose illness: The examples of interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1991;12:191-8.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Use and effectiveness of psychological self-care strategies for interstitial cystitis. Health Care Women Int 1995;16:463-75.

- Webster D, Brennan T. Use and effectiveness of sexual self-care strategies for interstitial cystitis. Urol Nurs 1995;15:14-22.

- Taylor S. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. Am Psychol 1983;38:1161-71.

- Butler L, Banfield V, Svenison T, Allen K. Conceptualizing sexual health in cancer care. West J Nurs Res 1998;20:683-705.

- McLaughlin F, Marascuila L. Advanced nursing and health care research: Quantification approaches. London: WB Saunders, 1990.

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: Method applications and issues Health Care Women Int 1992;13:313-21.

- Butler L, Banfield V. Oncology nurses views on the provision of sexual health in cancer care. J Sex Reprod Med 2001;1:35-44.

- Thorne S, Patterson J. Shifting image of chronic illness. Image: J Nurs Scholar 1998;30:173-7.

- Showers C, Abramson L, Hogan M. The dynamic self: How the content and structure of the self-concept change with mood. J Person Soc Psych 1998;75:478-93.